A new analysis of Cassini observations of Jupiter shows that an “inverse energy cascade” mechanism could be supplying the energy that powers and maintains the intense jet streams that typically rip through Jupiter’s atmosphere at the same speeds as much shorter-lived hurricanes and tornadoes do on Earth. “Exactly what mechanism generates and perpetuates dozens of ferocious, relatively constant jet streams that have been observed on Jupiter over decades is a long-standing question,” said David Choi, a student at the University of Arizona.

Earlier observational and modeling studies implied that inverse energy cascading occurs on Jupiter, Choi said.

“An inverse energy cascade is the transfer of energy from a local scale — local winds or small vortices, for example — to very large-scale circulations, such as big vortices and jet streams,” Choi said.

“Imagine if you took a thin coffee stirrer and stirred only one small corner of your coffee within the cup. If there is an inverse energy cascade present, the small stirring would eventually generate a big swirl that encompassed the entire cup, similar to what you would get if you were stirring with a big spoon,” he said.

“In theory, the cascade of energy on Jupiter can grow from local phenomena, such as a thunderstorm, to planetary-scale phenomena, such as the planet’s Great Red Spot or its jet streams,” he said.

Choi used a new approach in analyzing numerous images taken by the Cassini spacecraft when it flew by Jupiter in 2000 on its way to Saturn.

Choi analyzed pairs of Cassini images taken at slightly different times using automated software he developed for tracking cloud features that move with the wind. He compiled the results, made from hundreds of Cassini images, into a near-global wind vector map of Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Further analysis of the wind vector maps disclosed new evidence that the inverse energy cascade process supplies the energy that forms and sustains Jupiter’s numerous jet streams.

And that energy is considerable.

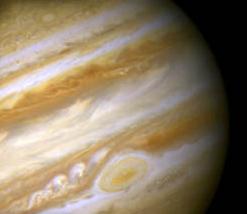

Jupiter’s atmosphere is essentially an alternating pattern of eastward and westward jet streams. Roughly a dozen jet streams populate each hemisphere of the giant planet. These jet streams are remarkable not just for their intensity, but for their longevity — observers have seen jet streams persist in their locations for decades, and in the case of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, for centuries.

Earth, by comparison, has one, sometimes two, eastward jet streams in each hemisphere, and they vary in strength and location according to the season. Earth’s jet streams flow from between 50 to 150 mph (80 to 240 kph) on average.

Jovian jet streams typically flow at around 100 mph (160 kph). But other jet streams on Jupiter consistently flow at speeds around 300 mph (480 kph). By comparison, typical speeds for tornadoes and winds near the eyes of hurricanes on Earth is roughly 100 mph (160 kph). The big difference is that hurricanes last for about a week, and tornadoes, destructive as they are, usually last only 10 to 30 minutes on the ground, Choi said.

Evidence for inverse energy cascades occurring in Earth’s atmosphere is speculative, and it is not the mechanism that energizes Earth’s jet streams, he said.