Key Takeaways:

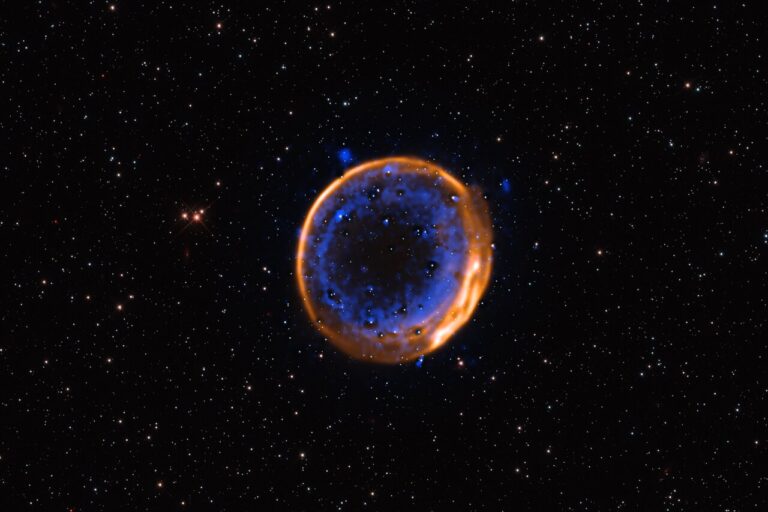

[Bottom-Left] — An enlargement of the boxed field in the top image reveals myriad stars and numerous open star clusters as bright blue knots. Hubble’s bird’s-eye view of M31 allowed astronomers to conduct a larger-than-ever sampling of star clusters that are all at the same distance from Earth, 2.5 million light-years. The view is 4,400 light-years across.

[Bottom-Right] — This is a view of six bright blue clusters extracted from the field. Hubble astronomers discovered that, for whatever reason, nature apparently cooks up stars with a consistent distribution from massive stars to small stars (blue supergiants to red dwarfs). This remains a constant across the galaxy, despite the fact that the clusters vary in mass by a factor of 10 and range in age from 4 million to 24 million years old. Each cluster square is 150 light-years across.

By nailing down what percentage of stars have a particular mass within a cluster, or the Initial Mass Function (IMF), scientists can better interpret the light from distant galaxies and understand the formation history of stars in our universe.

The intensive survey, assembled from 414 Hubble mosaic photographs of M31, was a unique collaboration between astronomers and “citizen scientists,” volunteers who provided invaluable help in analyzing the mountain of data from Hubble.

“Given the sheer volume of Hubble images, our study of the IMF would not have been possible without the help of citizen scientists,” said Daniel Weisz of the University of Washington in Seattle.

Measuring the IMF was the primary driver behind Hubble’s ambitious panoramic survey of our neighboring galaxy called the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury (PHAT) program. Nearly 8,000 images of 117 million stars in the galaxy’s disk were obtained from viewing Andromeda in near-ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths.

Stars are born when a giant cloud of molecular hydrogen, dust, and trace elements collapses. The cloud fragments into small knots of material that each precipitate hundreds of stars. The stars are not all created equally: Their masses can range from 1/12 to a couple hundred times the mass of our Sun.

To the researchers’ surprise, the IMF was very similar among all the clusters surveyed. Nature apparently cooks up stars like batches of cookies with a consistent distribution from massive blue supergiant stars to small red dwarf stars. “It’s hard to imagine that the IMF is so uniform across our neighboring galaxy given the complex physics of star formation,” Weisz said.

Curiously, the brightest and most massive stars in these clusters are 25 percent less abundant than predicted by previous research. Astronomers use the light from these brightest stars to weigh distant star clusters and galaxies and to measure how rapidly the clusters are forming stars. This result suggests that mass estimates using previous work were too low because they assumed that there were too few faint low-mass stars forming along with the bright massive stars.

This evidence also implies that the early universe did not have as many heavy elements for making planets because there would be fewer supernovae from massive stars to manufacture heavy elements for planet building. It is critical to know the star formation rate in the early universe — about 10 billion years ago — because that was the time when most of the universe’s stars formed.

The PHAT star cluster catalog, which forms the foundation of this study, was assembled with the help of 30,000 volunteers who sifted through the thousands of images taken by Hubble to search for star clusters.

The Andromeda Project is one of the many citizen science efforts hosted by the Zooniverse organization. Over the course of 25 days, the citizen-scientist volunteers submitted 1.82 million individual image classifications — based on how concentrated the stars were, their shapes, and how well the stars stood out from the background — which roughly represents 24 months of constant human attention. Scientists used these classifications to identify a sample of 2,753 star clusters, increasing the number of known clusters by a factor of six in the PHAT survey region. “The efforts of these citizen scientists open the door to a variety of new and interesting scientific investigations, including this new measurement of the IMF,” Weisz said.