On May 20, 2025, President Donald Trump announced plans to construct the “Golden Dome,” a multibillion-dollar missile defense system that would utilize space-based weapons and satellites to intercept ballistic attacks against the United States. This announcement stems from Trump’s Jan. 27 executive order titled “Iron Dome for America.” Inspired by Israel’s Iron Dome and President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, Trump’s executive order declared his commitment to “deploying and maintaining a next-generation missile defense shield.”

For some, this initiative marks a significant shift from the long-standing principle that space should be used for peaceful purposes. A version of this principle was enshrined in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which banned signatories from placing nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in space, and designated celestial bodies as a domain for exclusively peaceful use. However, the treaty does not prohibit all military activities in Earth orbit, including conventional weapons systems like the Golden Dome. Still, the Golden Dome is viewed by many analysts as an escalation in the militarization of space.

What is the Golden Dome?

Trump’s Golden Dome will be a missile defense shield utilizing a constellation of satellites and space-based weapons to intercept ballistic missile attacks against the United States. In his May 20 announcement, Trump said that his administration had chosen an architecture for the program and that the system could be operational within three years, before the end of his second term.

“Once fully constructed, the Golden Dome will be capable of intercepting missiles even if they are launched from other sides of the world and even if they are launched from space, and we will have the best system ever built,” Trump said, as reported by The Washington Post, in the Oval Office. At the same briefing, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth described the project as a “game changer.”

The system is designed to counter increasingly sophisticated threats from countries such as Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. According to the Pentagon, these nations have developed advanced long-range weapons, including ballistic, hypersonic, and cruise missiles capable of striking the United States with conventional or nuclear warheads.

How would it work?

The proposed “Golden Dome” missile defense system, described by Hegseth in a May 20 statement as a “system of systems,” aims to detect, track, and intercept missile threats before impact. Echoing President Ronald Reagan’s proposed Strategic Defense Initiative — often nicknamed “Star Wars” for its futuristic ambitions — Golden Dome would blend existing missile defense technologies with as-yet undeveloped systems.

The first layer of Trump’s Golden Dome would expand the deployment of current ground-based missile defenses, which are already adept at tracking and intercepting intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Beyond this, a constellation of new satellites would be tasked with monitoring emerging threats from space, including hypersonic missiles and Fractional Orbital Bombardment Systems (FOBS), which can evade traditional radar detection. This dedicated sensor layer would identify launch sites and missile types and track the trajectory of these new missile types.

The final phase envisions the development of space-based interceptors, the most controversial step. While the design for these interceptors remains unclear, they will effectively utilize data from the sensor layer to target advanced missile types during the initial boost phase, when vehicles are still gaining speed and are most vulnerable. At present, this technology does not exist.

The challenge here, according to space systems expert Patrick Binning, “is speed.” In an interview with Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering, Binning explained, “These early phases last only 10 to 20 minutes, and decisions must be made in seconds. Golden Dome must rapidly detect the launch, identify the threat type, calculate an intercept solution, and execute all in near real time.”

U.S. officials have consistently framed the Golden Dome as a defensive system. However, if the U.S. manages to introduce these space-based interceptors, the technology could be used for offensive capabilities.

The Space Force has recently shifted its public stance on the final frontier, treating it explicitly as a potential battleground. As Gen. Chance Saltzman stated in a 2024 story from Ars Technica, “Space is a war-fighting domain. Ten years ago, I couldn’t say that. That’s the starting point.” Such statements have prompted debate over whether the Golden Dome would remain a purely defensive measure or contribute to the weaponization of space.

What are the concerns surrounding the Golden Dome?

The announcement of the Golden Dome has provoked strong reactions both internationally and domestically. While supporters view it as essential for national security, critics have raised concerns about the project’s potential to trigger a new arms race, as well as its feasibility and cost.

China’s Foreign Ministry warned, as reported by Reuters, that the system “violates the principle that the security of all countries should not be compromised and undermines global strategic balance and stability.” Similarly, AFP reported that North Korea’s foreign ministry condemned the plan as “the height of self-righteousness [and] arrogance,” warning it could “turn outer space into a potential nuclear war field.”

These reactions highlight concerns that the Golden Dome could accelerate a space arms race. Hong Min, an analyst at the Korea Institute for National Unification in Seoul, told AFP: “If the US completes its new missile defense programme, the North will be forced to develop alternative means to counter or penetrate it.”

Domestically, the project faces scrutiny over its feasibility and cost. Senator Jack Reed, the top Democrat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, described the initial funding as “essentially a slush fund at this point,” according to The Washington Post, noting the absence of a detailed implementation plan. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that deploying and operating just the space-based interceptors could cost between $161 billion and $542 billion over the next two decades, significantly higher than Trump’s $175-billion projection.

Leading scientific organizations have also voiced skepticism about the Golden Dome. The American Physical Society, in a study published in March, found that developing an effective defense against even a small number of ICBMs would be a “daunting challenge” and that the problems associated with a large-scale missile defense system are likely to “remain formidable over the 15-year time horizon the study considered.”

Meanwhile, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) pointed to the U.S.’ historical record when it comes to missile defense. In a Jan. 28 statement, Dr. Laura Grego, research director and senior scientist for the Global Security Program at UCS, alleged, “Over the last 60 years, the United States has spent more than $350 billion on efforts to develop a defense against nuclear-armed ICBMs. This effort has been plagued by false starts and failures, and none have yet been demonstrated to be effective against a real-world threat.”

What are the potential consequences of space militarization?

Trump’s Golden Dome represents a significant step in the militarization of space — a trend at odds with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty’s vision of space as a realm for peaceful exploration and scientific advancement.

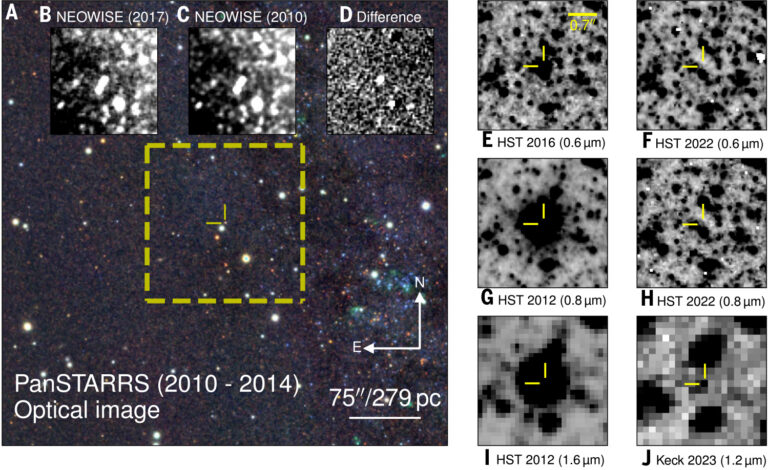

A full-scale war in space would carry significant risks, including the threat of space debris. As Colonel Shawn Fairhurst of Air Force Space Command warned in a 2018 story in Astronomy, “The problem is, when you blow something up in space, it creates debris that never comes down.” A single anti-satellite weapon test by China in 2007 created over 3,000 trackable debris objects — the largest space debris cloud in history — posing ongoing hazards to satellites in orbit.

Satellites are also vulnerable to nuclear detonations in space. In addition to releasing energy in the blast itself, a nuclear explosion generates an electromagnetic pulse (EMP), which can disable satellites and ground-based electronics across large areas. Nuclear explosions also release intense bursts of radiation and charged particles. Some of these particles can be trapped by Earth’s magnetic field, forming artificial radiation belts that can persist for months or year. This effect — demonstrated most notably in the aftermath of the 1962 U.S. Starfish Prime nuclear test in space — can severely damage or disable satellites in affected orbits.

The development of Trump’s Golden Dome also occurs against a backdrop of increasing competition in space. While the U.S., Russia, and China have all demonstrated anti-satellite capabilities, there has been a general reluctance to formalize rules that would constrain their actions. As P.J. Blount, an expert in space law, told Astronomy in 2018, “You see a lot of talk about wanting to de-weaponize space, but don’t see a lot of movement in defining the rules.”

Trump’s Golden Dome is seen by some as a pivotal moment in space policy, raising questions about the balance between national security and the peaceful vision of space exploration that the 1967 Outer Space Treaty championed.

Ultimately, as Col. Fairhurst warned, “Our whole goal is not to have a war in space. A war in space is not good for anybody.”