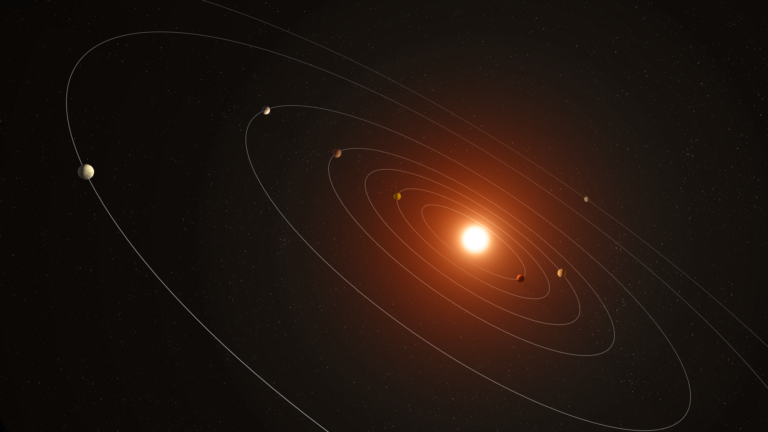

Following its successful collection of material from the asteroid 162173 Ryugu in 2019, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Hayabusa2 spacecraft swung by Earth to drop off its precious cargo in December 2020. But even as scientists continue to poke, prod, and zap grains of Ryugu to unlock their secrets, Hayabusa2 has been redirected to rendezvous with two additional asteroids: 2001 CC21 next year and 1998 KY26 in 2031.

The latter encounter just got a little more interesting, though, as astronomers announced today they’d discovered that 1998 KY26 is both smaller and rotating more quickly than initial observations indicated. In fact, it is so small that it’s roughly on par with the size of Hayabusa2 itself.

Small world

Based on data taken by several ground-based telescopes during 1998 KY26’s recent close approach to Earth last year and published today in Nature Communications, astronomers have now determined it is just 36 feet (11 meters) across. That’s roughly the width (not the length) of a doubles tennis court. It’s also one-third the size of previous estimates, which had pegged it at nearly 100 feet (30 m) in diameter.

According to JAXA, the Hayabusa2 spacecraft bus (the main body of the craft) measures 5.2 feet by 3.2 feet by 4.1 feet (1.6 m by 1 m by 1.25 m). Including its solar panels, Hayabusa2 is nearly 20 feet (6 m) across.

“The amazing story here is that we found that the size of the asteroid is comparable to the size of the spacecraft that is going to visit it!” said study first author Toni Santana-Ros, of the University of Alicante, Spain, in a press release.

What’s more, 1998 KY26 is spinning twice as fast as previously believed: It makes a full rotation every 5.4 minutes, rather than the previously measured value of about 10 minutes.

These would be nothing more than staggering stats if not for one thing: While Hayabusa2 will merely fly by 2001 CC21, it is aiming to briefly touch down on 1998 KY26 in a similar manner to its activities at Ryugu. On 2,960-foot (900 m) Ryugu, which spins once every 7.6 hours, that was a challenging but achievable maneuver. On tiny, fast-spinning 1998 KY26, it’s going to be a totally different ballgame.

“The smaller size and faster rotation now measured will make Hayabusa2’s visit even more interesting, but also even more challenging,” said European Southern Observatory (ESO) astronomer and study co-author Olivier Hainaut.

Measuring asteroids

Why were our previous estimates so far off?

Determining the shapes and sizes of asteroids is tricky. Traditionally, astronomers observe the asteroid — which appears as just a tiny point of light, even with powerful telescopes — as it moves through the sky, tracking subtle changes in brightness over time, called a light curve. Astronomers look for repeating patterns in the light curve, which allows them to map out different regions of the asteroid as it spins and determine how quickly it completes a full rotation. They also estimate its shape based on the light curve and calculate its size from the amount of sunlight it reflects — brighter asteroids are assumed to be bigger, and fainter ones assumed to be smaller.

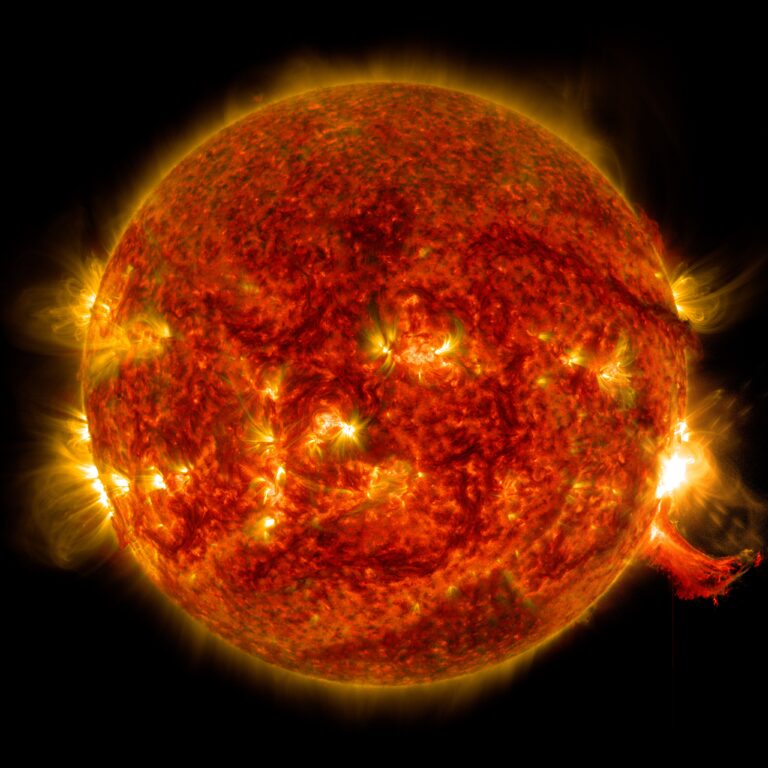

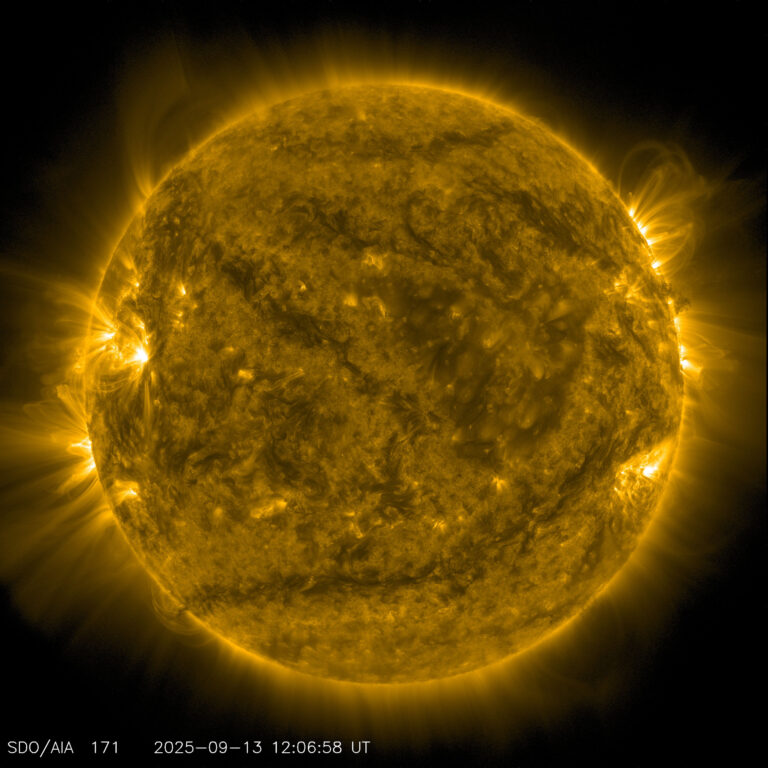

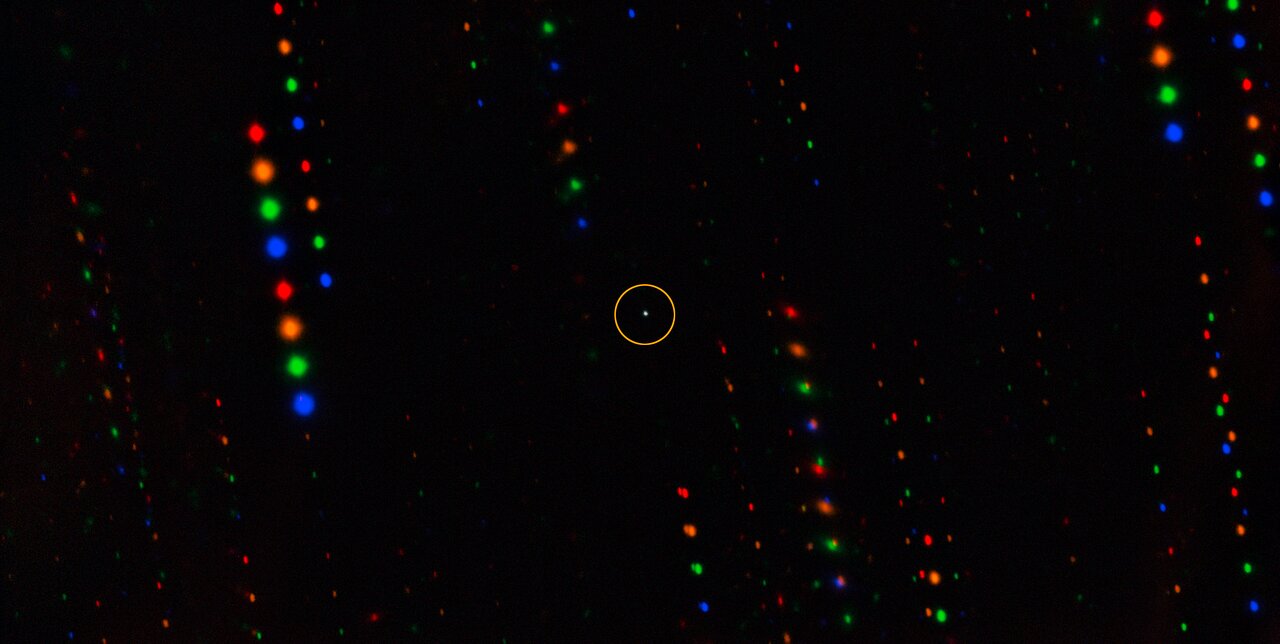

But this technique isn’t perfect and the more observations astronomers can take, the better. 1998 KY26 orbits the Sun once every 1.4 years at an average distance of about 114 million miles (183 million km), mostly outside Earth’s orbit (although it does briefly cross our orbit once during each of its orbits). According to the paper, since its discovery in 1998, 1998 KY26 never got brighter than magnitude 24 — some 10,000 times fainter than Pluto is currently. That made it difficult to study, but in spring 2024, 1998 KY26 passed close to Earth at about 12 times the distance of the Moon, making it appear brighter and ripe for detailed observation.

Telescopes such as ESO’s Very Large Telescope and the U.S.’s Gemini, SOAR, and Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope, all in Chile, peered at the space rock as it passed. The new light curves measured the asteroid’s spin as it was illuminated by the Sun from several different angles, which allowed a clearer picture of 1998 KY26’s shape and size. The new views revealed a smaller, faster-spinning asteroid than previously assumed — and, based on this new knowledge, one that reflects much more sunlight than previously assumed as well. Astronomers are now classifying it as an Xe-type asteroid, the only class known to reflect such a high amount of sunlight.

Answers await

The asteroid’s small size and fast spin also have implications for its structure. Ryugu, for example, is what astronomers call a rubble pile asteroid, made up largely of accumulated smaller bits of debris held together by gravity. But what about 1998 KY26, which is smaller and spins much faster than Ryugu? Could it even hold on to rubble on its surface as it spins, rather than flinging it out into space?

Astronomers say yes, but they also can’t rule out the possibility that 1998 KY26 is a single, solid rock all the way through, either. If it’s the latter, it may have once been a piece of a larger body that was thrown out during a collision. We’ll only be able to tell which scenario is correct once Hayabusa2 gets there. “We have never seen a 10-meter-size asteroid in situ, so we don’t really know what to expect and how it will look,” said Santana-Ros.

According to the paper, ground-based telescopes will not be able to obtain any further data on 1998 KY26 before Hayabusa2’s visit in 2031. However, the James Webb Space Telescope might be able to take a peek in March 2028 and January 2029, offering a chance to confirm the current size estimate and perhaps give clues to the asteroid’s temperature and density.

Understanding 1998 KY26 represents a valuable opportunity to learn more about the roughly 39,000 known asteroids whose orbits approach Earth’s. While 1998 KY26 is not itself considered a hazard, there are 2,508 currently known objects that do have orbits that bring them close enough to our planet to raise concerns. And, according to the study, asteroids the size of 1998 KY26 “are the most common objects that could cause critical effects on human activities if they impact the Earth.”

The recent measurements demonstrate the ability of current technology to characterize such small asteroids, bolstering future planetary defense efforts as we seek to understand the objects — particularly the small, stealthy ones — that populate our planet’s local neighborhood.