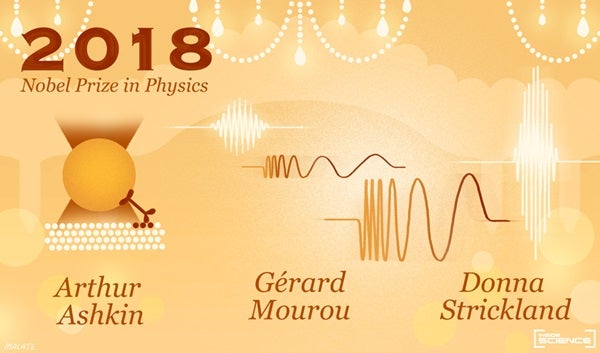

The first half of the prize goes to Arthur Ashkin from Bell Laboratories in Holmdel, New Jersey, “for the optical tweezers and their application to biological systems.” The second half was awarded jointly to Gérard Mourou of the École Polytechnique, Palaiseau in France, and Donna Strickland of the University of Waterloo in Canada, “for their method of generating high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulses.”

Ashkin’s “remarkable invention,” as Göran K. Hansson, the secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences called it during the prize announcement, used the pressure from laser light to move tiny objects like bacteria and viruses toward the center of a beam and hold them there.

The principle was demonstrated on video by Nobel committee member Anders Irbäck, who wielded a hair dryer to elevate a ping pong ball and move it around. The optical version — so-called optical tweezers — can capture and study living organisms without harming them.

The other two new laureates — Mourou and Strickland — made their innovation while working together at the University of Rochester in New York in the 1980s. Lasers had been invented around two decades earlier but had hit an intensity plateau because a laser beam that was too powerful could destroy the material used to amplify it. The two scientists came up with a way to stretch the laser pulse to reduce its peak power, then amplify it, and then compress it again. The technique, called chirped pulse amplification, enabled a steady progression toward ever shorter and more powerful laser pulses.

The millions of people who’ve undergone laser eye surgery have already directly benefited from Mourou and Strickland’s work. Ultrapowerful laser pulses can also probe the properties of matter and accelerate electrons and protons to high speeds, with applications in both basic science and pursuits like the treatment of cancer.

When Strickland was reached by phone during the press conference, a journalist asked her what she thought of being only the third woman to have been awarded a Nobel Prize in physics. She seemed surprised by the low number.

“Obviously we need to celebrate women physicists because we’re out there,” she said.

Strickland is the first female physics laureate in 55 years.

“I’m honored to be one of those women [Nobel laureates],” she said.

“We expect more to come,” Hansson assured the audience.

This story was originally published on Inside Science.