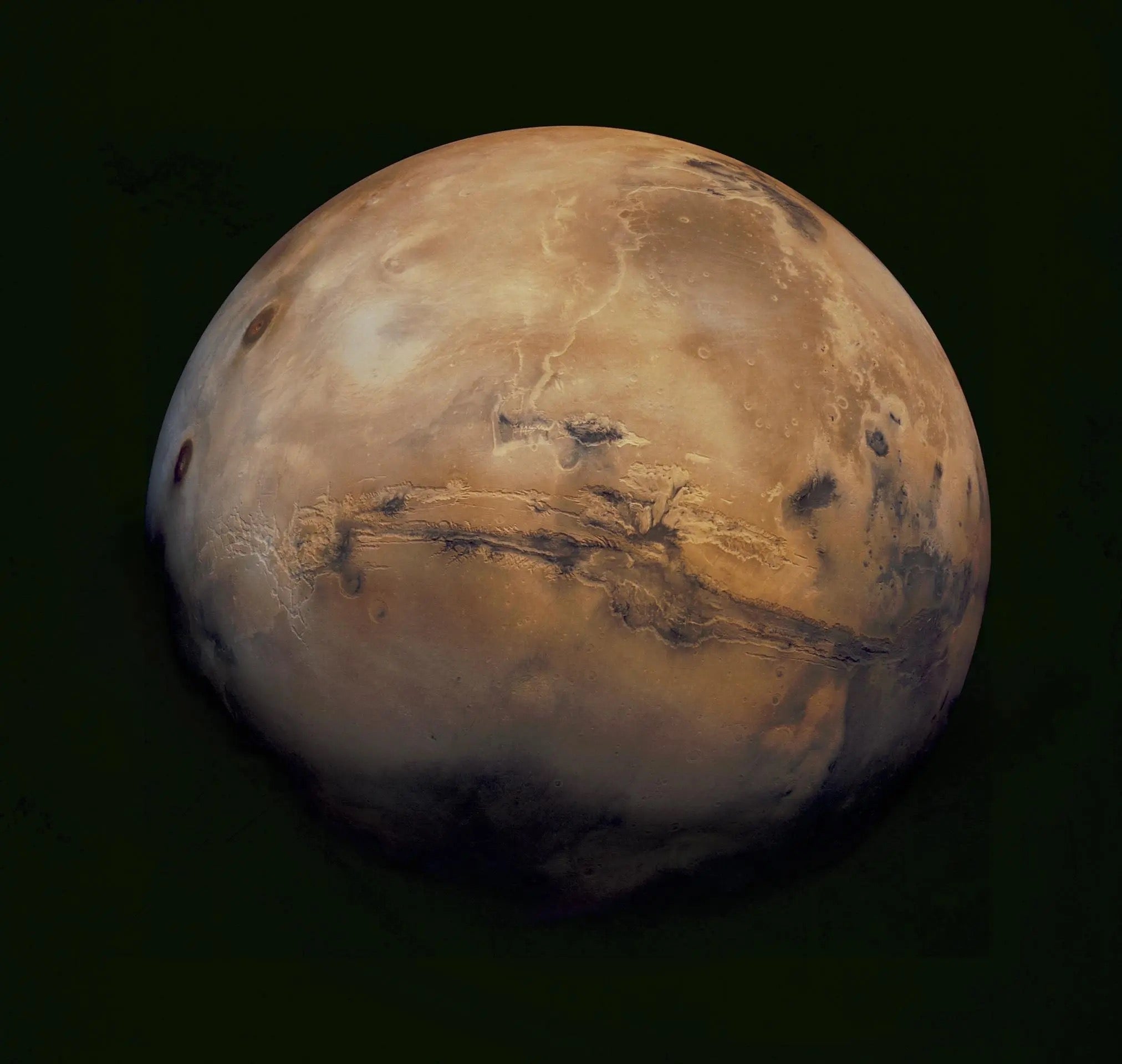

In early 2022, then-Ph.D. student Adomas Valantinas was at the University of Bern, sorting thousands of images of Mars snapped by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) spacecraft when he noticed vast swaths of odd material near the planet’s equator. Sifting through the pictures, he soon saw a pattern: the bluish deposits, which represent ice in TGO’s false-color images, were coating the tops of the tallest volcanoes on the planet near the parched martian equator, where planetary scientists thought it was impossible to form ice.

That’s because between Mars’ vanishingly thin atmosphere and the relatively abundant sunlight the equator receives, the region is too warm for frost to form — not just at the surface but also on mountaintops in the Tharsis region, which is home to numerous volcanoes including Olympus Mons, the largest in the solar system.

Frosty peaks

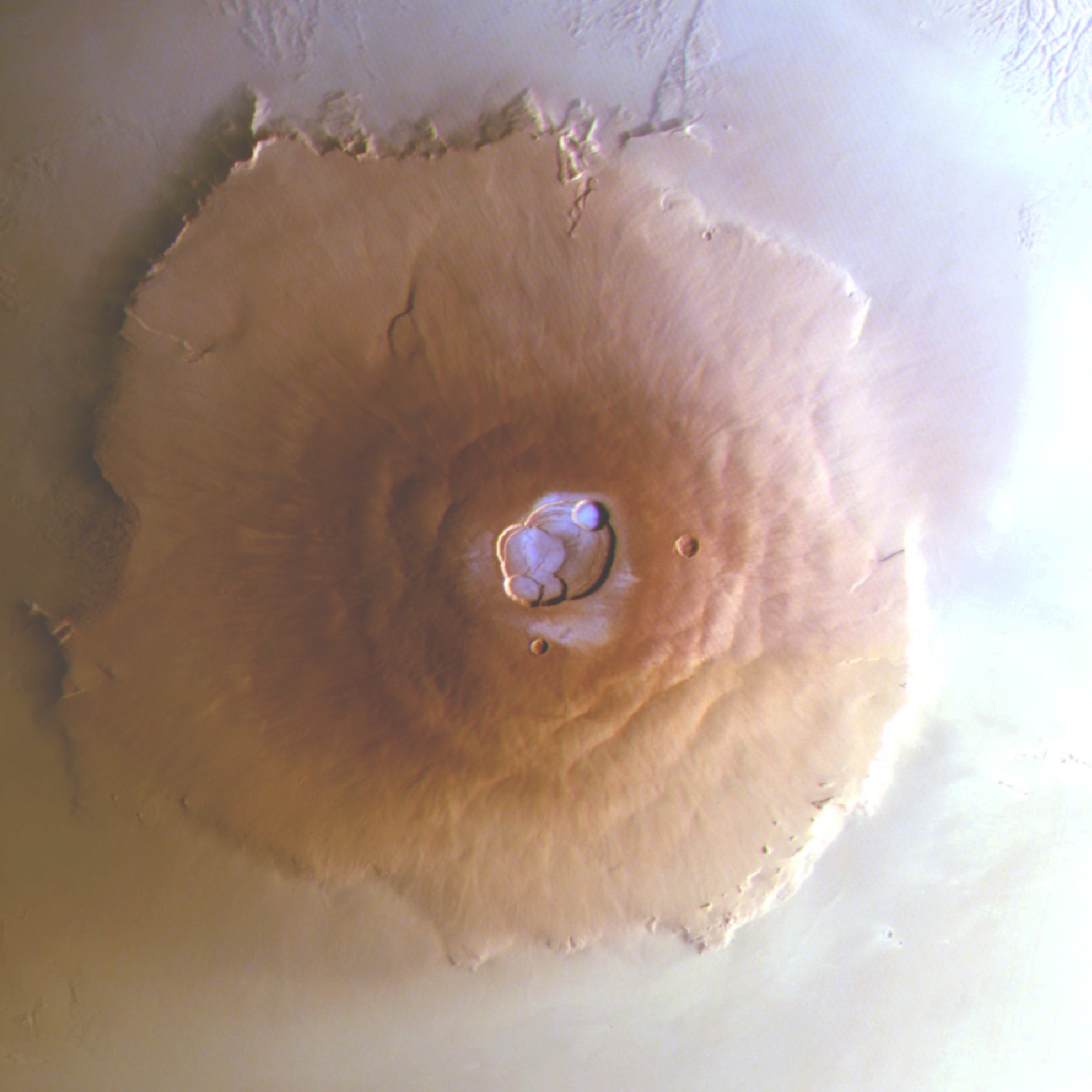

Yet, morning images during the wintertime from two instruments on TGO as well as from the Mars Express orbiter show frost briefly coating at least four colossal volcanoes: Olympus Mons, Arsia Mons, Ascraeus Mons, and Ceraunius Tholus. The newfound patches of ice, each only as thin as a strand of human hair, together contain 150,000 tons of water — enough to fill 60 Olympic swimming pools — the researchers estimate in a paper published June 10 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“Our study shows you can find water frost in areas where you would not expect,” says Valantinas, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University. “It is a modern-day process — it’s happening on present-day Mars.”

Related: Where did all the water on Mars go?

Every day during winter, early spring and late fall, the frost forms for a few hours around sunrise before evaporating into the thin martian air. While its ephemeral presence means future astronauts can neither use it for life support nor mine it for rocket fuel, scientists say the discovery can teach them plenty about Mars’ water cycle and will help them better decipher the planet’s complex atmospheric dynamics.

“It’s a desert planet but it still has this water cycle,” says Valantinas. “It could be that what we’re seeing now with this water frost is a remnant of this cycle that was more significant in the past.”

A unique microclimate

The morning frost was spotted in the volcanoes’ calderas, bowl-shaped features that form during eruptions when magma underneath oozes out and the sides of the volcano crumble inward. Valantinas and his colleagues propose that wind on Mars, which ferries moisture from the ice-capped poles, travels up the mountain slopes and into the calderas, where it condenses into patches of frost. By simulating wind patterns and speeds in the area, the researchers found the wind travels at lower speeds within the caldera than surrounding areas, thus allowing the frost to form. “It’s a special microclimatic condition there,” says Valantinas.

The team has ruled out other explanations for the frost, such as ice from carbon dioxide molecules, which constitute 95 percent of the planet’s air. Temperatures within the calderas when TGO snapped its images suggest “it is too warm for carbon dioxide frost to form,” says Valantinas. Another explanation for the ice could be that it forms from gases belched by the dormant volcanoes, which can then freeze to form frost, but “it would be quite difficult to explain why volcanic outgassing is seasonal,” he says.

Rather, water ice from the caps at the north and south poles evaporates during local summers, traveling to the opposite hemisphere and moving through the equatorial regions, where the Tharsis volcanic range resides. Valantinas and his team suggest that some of this water gets trapped in the volcanoes, which tower at heights up to two times that of Mount Everest.

This is “a decidedly Earth-like phenomenon,” Colin Wilson, a project scientist at ESAfor both TGO and Mars Express missions, who wasn’t directly involved with the new study, said in a statement. “Understanding exactly which phenomena are the same or different on Earth and Mars really tests and improves our understanding of basic processes happening on not only our home planet, but elsewhere in the cosmos