Astronomers may have witnessed the death of one of the most massive stars that can exist. A global collaboration of astronomers, led by Queen’s University in Belfast, teamed up with Japanese supernova-hunter Koichi Itagaki to report the discovery. This double explosion, the first of its kind to be observed, challenges our understanding of star-deaths.

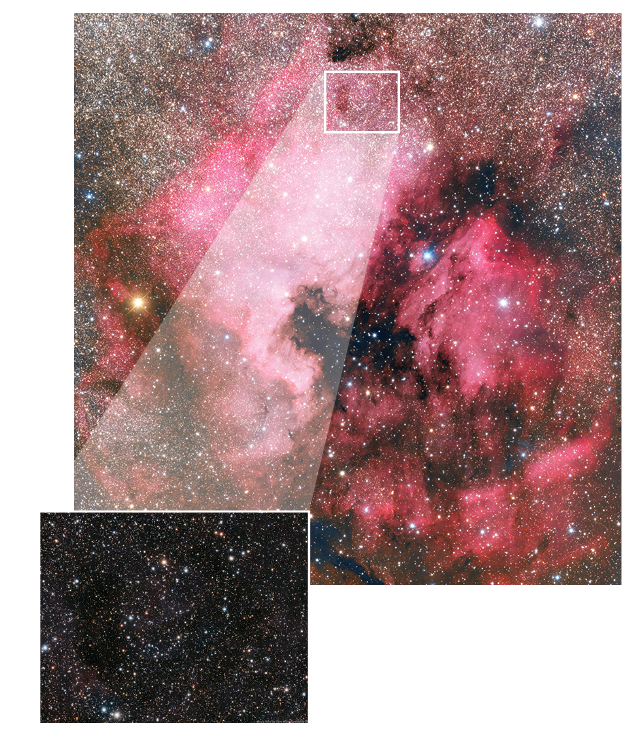

In 2004, Itagaki discovered an exploding star in the galaxy UGC4904 (78 million light-years away in the Lynx constellation), which rapidly faded from view throughout the next 10 days. The discovery was never formally announced to the community. Two years later, Itagaki found a new, much brighter explosion in the same place, which he proposed as a new supernova. Professor Stephen Smartt and Dr. Andrea Pastorello, astronomers at Queen’s, immediately realized the implications of such a finding.

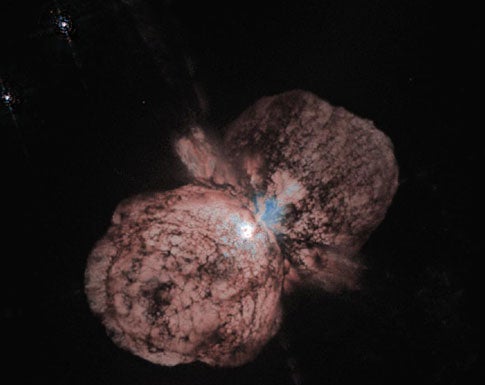

They began observing the 2006 supernova (SN2006jc) with a wide range of large telescopes, and analyzed Itagaki’s images to show that the two explosions were in exactly the same place. The most likely explanation for the 2004 explosion was an outburst of a star like Eta Carinae, which was observed to have a similar giant outburst in the 1850s. The 2006 supernova was the final death of the same star.

“We know that only the most massive stars can produce this type of outburst. So the 2006 supernova must have been the death of the same star, possibly a star 50 to 100 times more massive than the Sun,” Pastorello said. “And it turns out that SN2006jc is a very weird supernova — unusually rich in the chemical element helium, which supports our idea of a massive star outburst, then death.”

Pastorello used UK telescopes (the Liverpool Telescope and the William Herschel Telescope) on La Palma in a combined European and Asian effort to monitor the energetics of SN2006jc. He showed that the exploding star must have been a Wolf-Rayet star, the carbon-oxygen remains of originally high-mass stars.

Smartt received funding from a prestigious EURYI fellowship to study the births and deaths of stars. “The supernova was the explosion of a massive star that had lost its outer atmosphere, probably in a serious of minor explosions like the one Koichi found in 2004. The star was so massive it probably formed a black

hole as it collapsed,” he said. “This is the first time two explosions of the same star have been found, and it challenges our theories of the way stars live and die.”

Although this is the first time two such explosions have been found to be coincident, they could be more frequent than previously thought. The future Pan-STARRS telescope, which will contain the world’s largest digital camera, will be capable of surveying the whole sky once a week, and could search for these peculiar supernovae. Queen’s is a partner in the Pan-STARRS science team, and hopes to use it to understand how the universe’s most massive stars die.