Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius invented Canes Venatici in 1687 to honor the two hounds of Boötes the Herdsman, which he uses to drive Ursa Major the Great Bear away from his flock. To create the constellation, Hevelius used a scattering of stars “floating” between Boötes and Ursa Major. The southern hound he named Chara, the Greek word for “joy,” and the northern one he called Asterion, meaning “little star.”

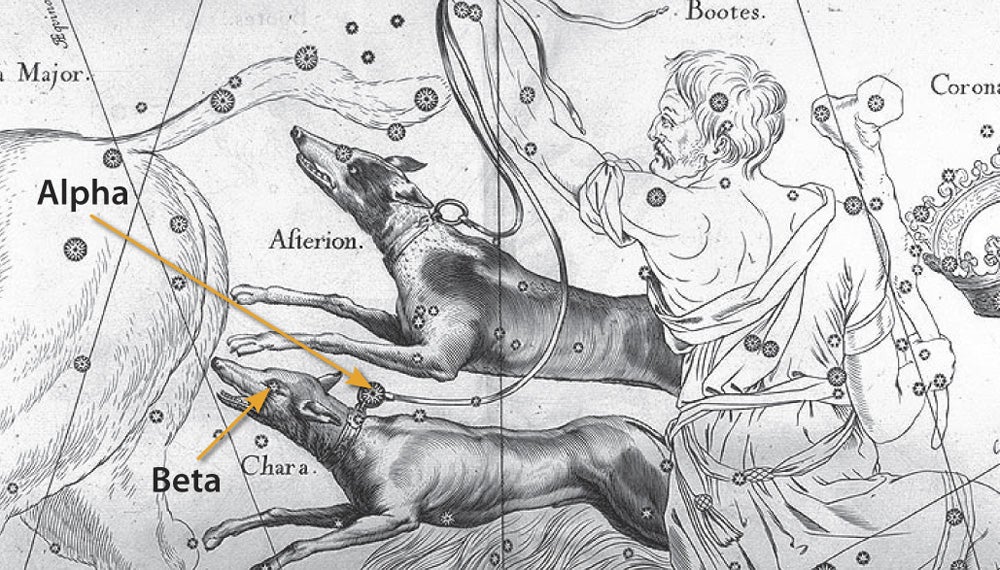

Hevelius depicted the two dogs in his 1690 star atlas. Here, Chara alone contains the constellation’s two brightest stars: 3rd-magnitude Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum, which marks the loop in Chara’s collar, and 4th-magnitude Beta (β) Canum Venaticorum, which marks that dog’s eye. Today, these are the two stars that most amateur astronomers recognize as Canes Venatici (CVn), but more on that later.

Stars of Asterion

Asterion’s stars pale in comparison to Chara’s, shining no brighter than 5th magnitude, making them a bear to see. The northern hound’s brightest, 20 CVn, burns at lowly magnitude 4.7, yet it has a prominent rank within about a 1°-wide asterism of four 5th- to 6th-magnitude stars lying about 5° to the east-northeast of Alpha CVn (which is a gorgeous telescopic double). This asterism marks Asterion’s right shoulder and is a guiding light to M63, a stunning Messier galaxy known as the Sunflower, just 1½° to the north-northwest.

Asterion’s next brightest star, 21 CVn, marks the back of the dog’s snout. It shines at magnitude 5.1 and lies only about 3° north-northwest of another extragalactic dynamo: the famous Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), which tickles one of Asterion’s ears.

Asterion’s northern leg also contains the variable star Y CVn, one of the coolest, reddest stars visible without optical aid. Known as “La Superba,” it varies from about magnitude 5.2 to 6.6 over 158 days.

While Asterion contains only these faint treasures, at one time during the hounds’ history, astronomers considered bright Beta CVn to be part of Asterion.

In 1725, English astronomer Edmond Halley officially bestowed upon Alpha CVn the name “Cor Caroli,” which honors King Charles I of England and means “Charles’ heart.” When King Charles II (yes, that King Charles II) returned to London at the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Alpha CVn was said to have blazed with uncommon brilliancy. While this is an interesting story, there is no relation between the name of the star and the celestial dog in which it lies.

England’s first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, did not include that new moniker in his 1729 Atlas Coelestis. He did, however, reposition Asterion further to the north, so that its body no longer hugged its companion, creating space for future renderings of Cor Caroli, like the one in Johann Bode’s 1801 Uranographia Sive Astrorum Descriptio: an image of Charles’ heart capped with a crown. In an attempt to link the politics to the dogs, Bode placed the heart at the top of Chara’s collar, where it connected to the leash that Boötes held.

And this is how matters more or less stood until the 1950 Skalnate Pleso Atlas of the Heavens came on the scene. Its creator, Czech astronomer Antonin Becvar, assigned Alpha CVn to Chara and Beta CVn to Asterion and connected the two stars with a leash. Now, many beginning observers learn to identify the two hounds based on Becvar’s image. While this notion erases a fascinating history, it at least makes sense: It associates the “little” star, Beta CVn, with Asterion, and the more “joyous” star, Alpha, with Chara, who wears the king’s heart collar.

But that’s just not how it is on many modern atlases, and not how it was when Hevelius first depicted the dogs. Alpha still remains Cor Caroli; Beta, however, is no longer Asterion, but Chara. Asterion has vanished from the scene — a faded memory of a dog that once guided backyard astronomers to deep-sky riches. Asterion’s region has, once again, become a large and lonely void. Without your careful eye, Hevelius’ original artistry may be forgotten.

As always, send thoughts to someara@interpac.net.