Scholars have long known the Classic Maya (300-900 C.E.) were astronomers. Their pyramids at sites like Tikal and Chichen Itza were precisely aligned with solstices, equinoxes, and planetary cycles, and their surviving texts, like the Dresden Codex, contain sophisticated tables for predicting solar eclipses.

New research published Nov. 5 in Science Advances on the oldest and largest monument yet found in the Maya area, Aguada Fénix, proposes that this deep connection to the sky may extend back even further. The authors of the paper, led by University of Arizona archaeologist Takeshi Inomata, argue this massive site, built between 1050 and 700 B.C.E., was likely designed as a “landscape-wide cosmogram.” Serving as a physical representation of their cosmology, or knowledge of the universe, the Maya constructed this cosmogram using sacred astronomical knowledge centuries before the rise of powerful kings.

The authors propose this massive project wasn’t led by a powerful ruler, but by “leading figures, who had specialized skills and knowledge of astronomical observations and calendrical calculations.” These early astronomers, the authors write, “probably did not have coercive power, but their esoteric knowledge may have earned them respect, enabling them to persuade large numbers of people to participate in constructions and rituals.”

Mesoamerican cosmological context

For millennia, premodern societies created maps of the skies, and for the ancient Maya, the gods and heavens were inseparable. Scholars understand their worldview as a sacred, ordered space, often based on a cruciform, or cross, shape representing four cardinal directions. Each direction had associated meanings, all meeting at a central point connecting the heavens, Earth, and underworld.

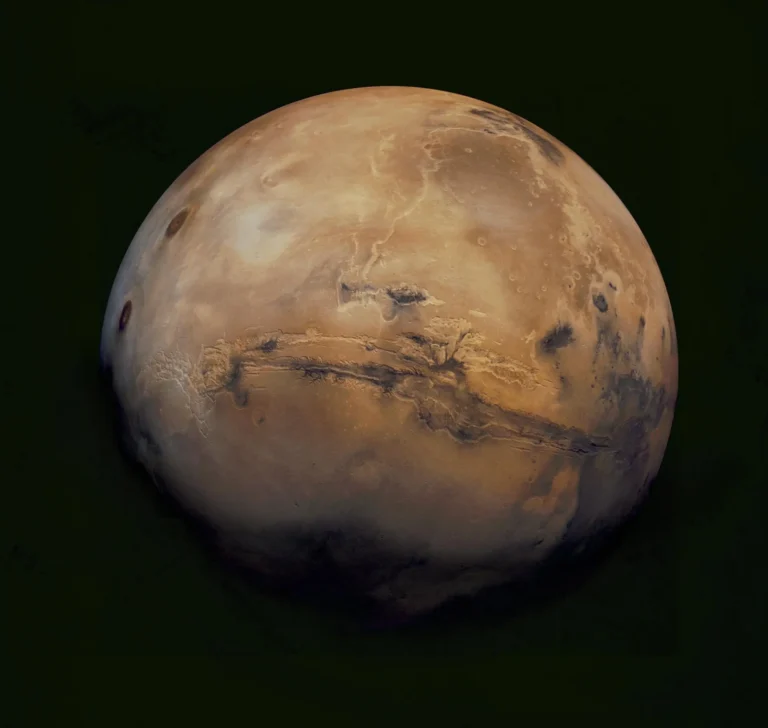

Using their knowledge of astronomy and mathematics, the ancient Maya developed one of the most accurate calendar systems in human history. This system was governed by interweaving cycles of time, chief among them the Haab, a 365-day solar-year calendar, and the Tzolk’in, a 260-day sacred calendar. The Tzolk’in is not divided into months. It functions like two interlocking gears: a smaller gear with the numbers 1 through 13, and a larger gear with 20 different day glyphs. A single day is named by the combination of a number and a glyph. Because the two gears have different numbers of “teeth,” it takes 260 days for a specific combination to repeat itself. This sacred calendar was the heart of Mayan ritual life; its 260-day length matches the gestational period of humans, nine cycles of the Moon, is related to the movements of the zenith Sun, and aligns with the growing cycle of corn.

The discovery at Aguada Fénix

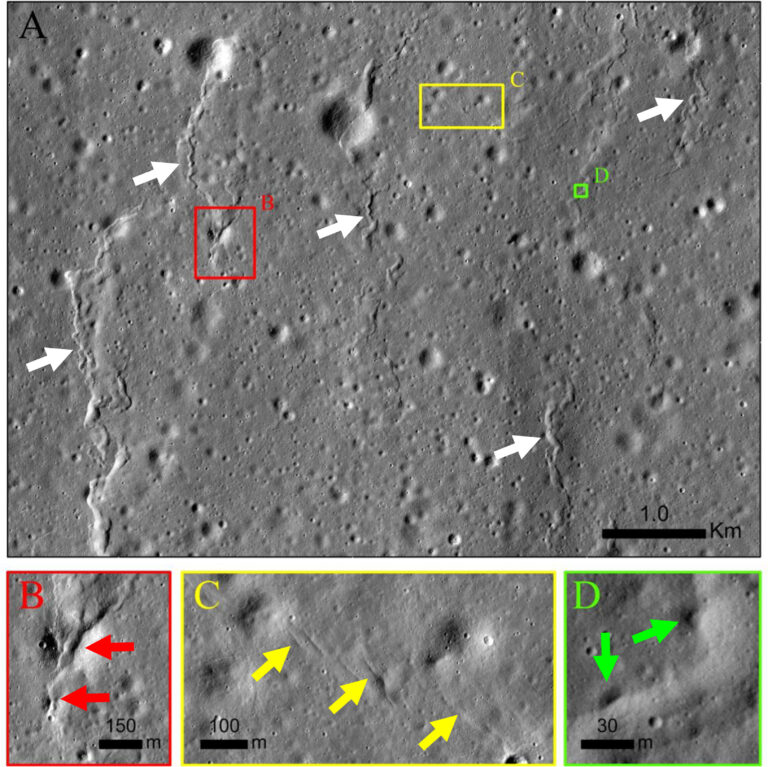

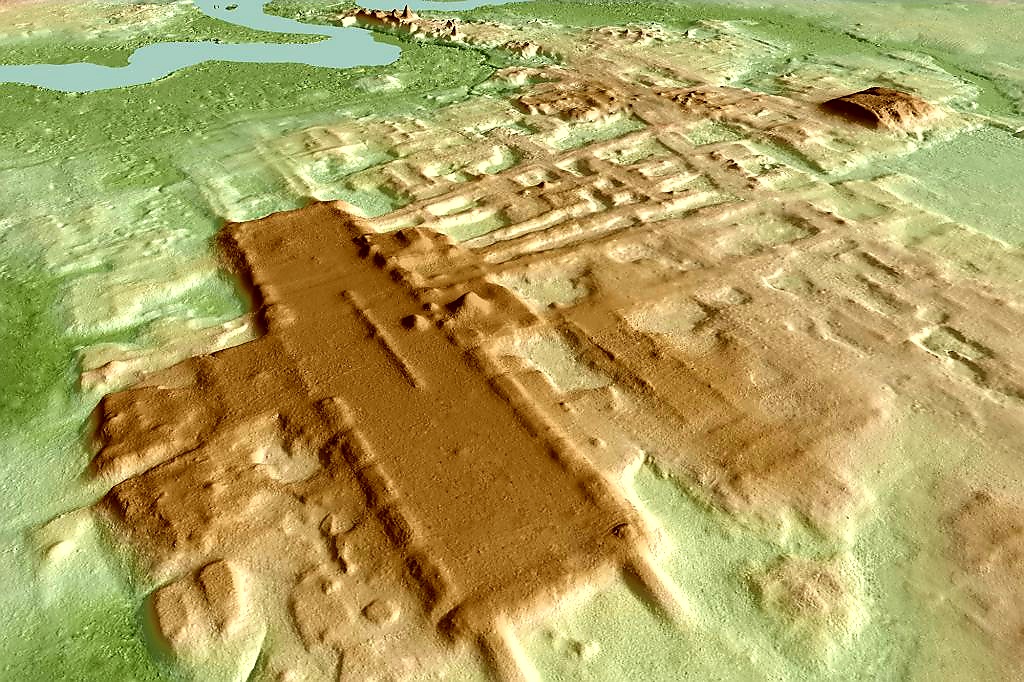

The new paper focuses on Aguada Fénix, located in southeastern Mexico in the state of Tabasco. Using airborne lidar – a remote-sensing method that allows archaeologists to see beneath vegetation to landforms and structures, using lasers to determine distances by measuring the time a pulse takes to return – archaeologists uncovered a monumental artificial plateau. It is described as the largest in Maya history, measuring 4,593 by 1312 feet (1400 by 400 meters).

The site’s construction is dated to between 1050 and 700 B.C,E., placing it centuries before the rise of later, well-known Maya cities. While the platform itself is massive, the authors argue it is only the center of a far grander design. They suggest the entire site, defined by corridors and canals with axes stretching 5.5 by 4.6 miles (9 by 7.5 kilometers) across the landscape, was laid out as a deliberate cosmogram.

Evidence for a cosmic blueprint

The paper lays out several lines of evidence to support the claim that the site was a massive cosmogram and ritual complex.

First, the site’s central architectural feature is a specific layout known as an E Group. This is a general term for an architectural arrangement found at many Maya sites, typically consisting of two western mounds and an elongated eastern platform, which served as a focal point for community rituals. The name comes from the first discovery of this arrangement at Uaxactún, in an area of the site archaeologists labeled “Group E.” The paper highlights that the E Group at Aguada Fénix was potentially purpose-built to align with the sunrise on Feb. 24 and Oct.17.

The authors note that those dates are not random. The interval between them is 130 days – a significant number, as 130 is exactly half of the 260-day sacred Tzolk’in calendar. The authors posit that this alignment represents a link between the monument’s orientation and this key ritual cycle.

Further supporting the cosmogram theory is a key discovery made at the very center of the E Group. Archaeologists found a large ritual pit, measuring roughly 19 by 18 feet (5.8 by 5.5 m), dug in a cruciform shape. The paper notes it had stepped accessways on each of its four sides and was coated in white clay. Inside this pit, they found a ritual cache containing a lump of black clay adorned with blue pigment in its northern part, green in the east, and yellow in the south, alongside symbolic marine shells (thought to also represent the cardinal directions), and 24 axe-shaped clay objects.

The paper describes this discovery as the “earliest known expression of directional color symbolism in Mesoamerica.” While the act of assigning colors to directions became a core concept for the later Maya, the authors note that the specific colors at Aguada Fénix (blue/north, green/east, yellow/south) differ from the Classic Maya pattern (red/east, white/north, black/west, yellow/south) that researchers have been familiar with for years. The authors also find it intriguing that blue and green pigments were used for different directions, as many later Maya languages used a single word, yax, to describe both colors.

The authors propose that this combination of a cross-shaped pit — mirroring the four cardinal directions — and the deliberate placement of specific colors in their corresponding directions was a way of physically marking the symbolic center of the site-wide cosmic map.

A new picture of early Maya society

If this interpretation is correct, the finding challenges previous assumptions that such large-scale, cosmically-aligned projects only appeared much later with the rise of centralized, king-led polities.

The authors propose that the spiritual and communal significance of building this massive cosmogram — a physical manifestation of the order of the universe for the Maya — likely provided the shared rationale for such a large number of people to participate in the project. The paper suggests this was a community coming together, united by a shared set of cosmic beliefs.

Instead of a king, the authors suggest the project was likely designed by central figures with specialized skills in astronomical observation and calendrical calculations. The paper posits that these “calendrical specialists” were not rulers, but community leaders who likely lived at Aguada Fénix year-round to conduct astronomical observations from fixed locations.

According to this model, these specialists did not exert state power to force participation. Instead, their knowledge of the cosmos and calendar may have earned them the respect needed to persuade large numbers of people to join the rituals and construction. The paper suggests these specialists formed an “emergent elite” who also managed trade for prestige items like jade and pigments.

This group, the authors conclude, provided the “prototype for later Maya rulers.” In later Classic Maya civilization, kings and elites would similarly derive their authority from acting as the holders of sacred calendrical and astronomical knowledge, positioning themselves as the “embodiment of universal orders.” The authors conclude that the Maya’s fascination with the cosmos was not just a late-stage feature of their civilization, but may have been the very “blueprint” for it.