First the Moon. All future strangeness happens because Earth’s tidal bulge doesn’t sit precisely under the Moon. Our rapid spin pushes the ocean’s yard-high surge ahead of the Earth-Moon line. So, the Moon actually pulls backward on this bulge, slowing the Earth’s rotation gradually. Earth’s day lengthens by 1¼500 of a second per century.

This additional time is not enough for us to meddle with clocks annually, contrary to the leap-second myth. Still, 1 second each 500 centuries does add up. We’ll have a 30-hour day in just a billion years. Before you know it, you’ll have enough time to call Mom.

Then, for millions of years, one side of Earth will face the Moon. Half the world will watch the Moon hover above for what seems like forever, while the other half will never see it. Who gets the Moon: China or us? No way to know — the continents will have drifted into new patterns by then.

This stable situation is where the story might end, except the Sun has something to say about it, too. Today, the Sun’s tidal pull on Earth is only half as strong as the Moon’s. But as the Moon departs, the Sun grows relatively more influential.

Ultimately, it makes Earth spin even slower than its new once-a-month rotation. Angular momentum then harasses the Moon again, this time by robbing it of energy. Thus begins the era when the Moon starts falling toward us.

Fortunately for humanity’s fate, the Moon will break apart before it reaches 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers) away because its silicate rocks are only half as dense as Earth’s heavier materials.

Voilà! Earth gets a ring even more glorious than Saturn’s. Pencil it in around 3 billion years from now.

Along the way, total solar eclipses will end. In another 60 million years or so, the Moon will appear too small to cover the Sun. And lunar tides, which vary with the cube (not square) of the Moon’s distance, will become pussycat weak.

Have you seen the tidal bore at Truro in Nova Scotia? From a hilltop, you watch a 2-foot wall of ocean march around a bend and turn the sandy beach below you into a rushing river. Later, it reverses direction. You gotta see it! It’ll cease in less than a billion years, so don’t wait.

Before then, expect the next big asteroid impact. The K-T extinction 65 million years ago wasn’t too bad if you’re pro-mammal and anti-reptile. But the one before that, 251 million years ago, left only 2 percent of Earth’s species intact. Could we fare better than those creepy trilobites? If so, could we handle a planet where only 2 percent of our favorite snacks remain? Supermarkets with nothing but row after row of different brands of kelp?

Say we make it through that. The next challenge comes in 1.1 billion years, when the Sun is 10 percent brighter and the oceans have boiled off. Do we head below ground and wait it out? We could learn from the Canadians, whose amazingly vast labyrinths beneath Toronto and Montreal house rock concerts and restaurants. By then, maybe we’ll have emigrated to a planet with lower taxes.

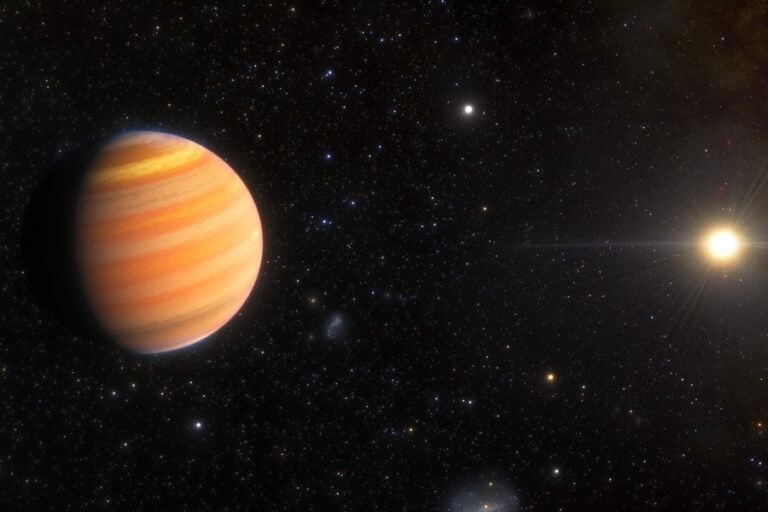

If we stay, things only get worse. In 7 or 8 billion years, the Sun turns into a red giant. Its surface expands beyond Venus’ orbit and could venture past us (see May 2005’s Ask Astro, page 66). Although we shouldn’t knock something we haven’t tried, orbiting inside the Sun can’t be a great experience.

So off we’ll go, bringing stockcar racing to Mars. We load up a spacefaring ark with two of each of Earth’s species, except for amoebas, where one is enough.

Hmm, let’s see, 90 million species, times 2. No small job. We could save room by leaving mosquitoes and those nervous little dog-breeds behind. Too complicated.

We’ll just have to take care of this place now. And “now” is what matters because we — not the Moon — likely will decide if this will be a Paradise Lost.