For millions of students and teachers, September means back to school. And that means tests. For many, this topic may be a bit traumatic.

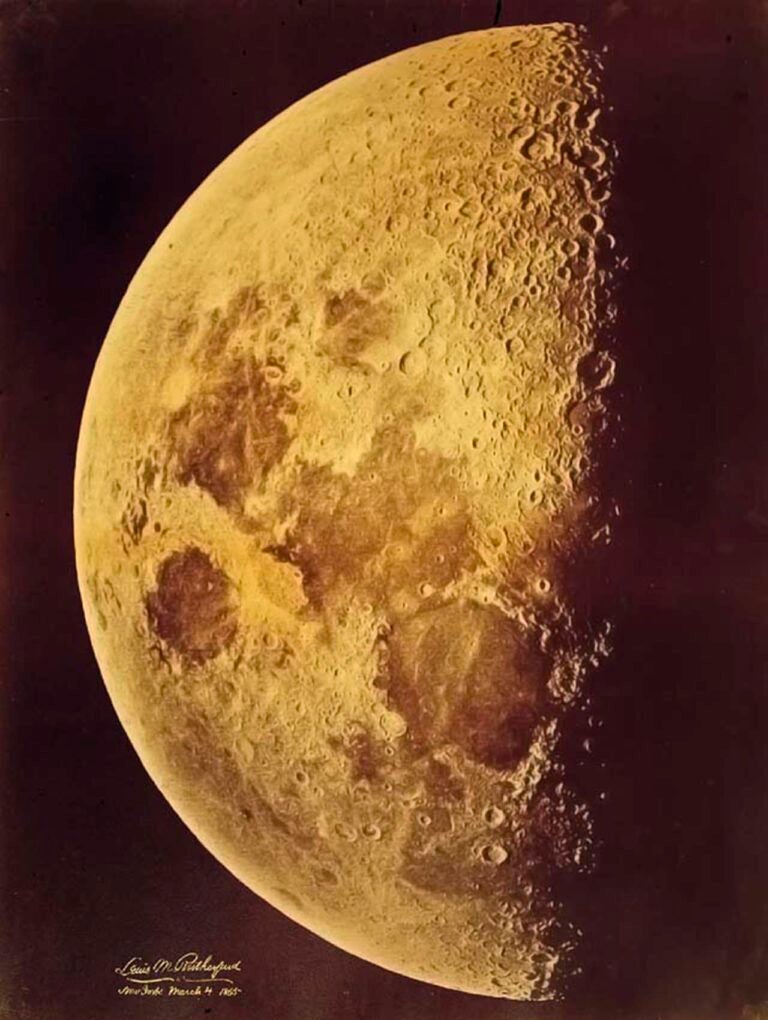

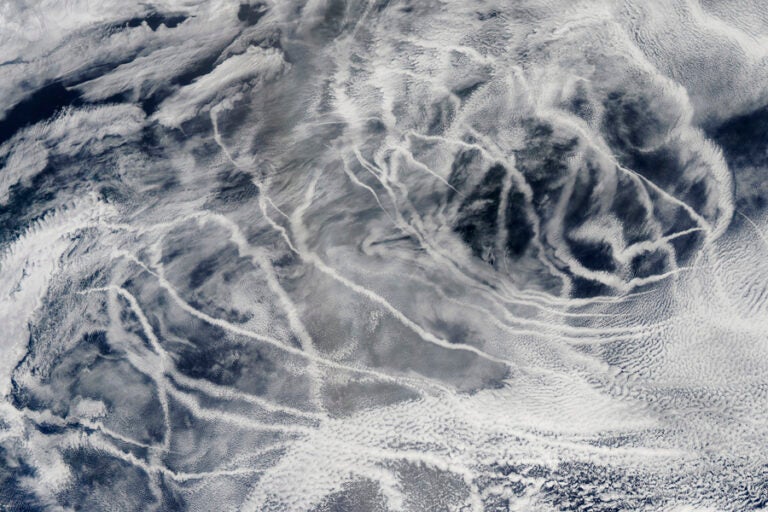

Yet we backyard astronomers seem to enjoy testing ourselves and our friends. We change the eyepiece, focus on the Moon’s bright face, and ask, “Can you see the five little craters inside of Clavius?” Maybe we just love challenges. Various celestial disciplines such as optics, planetary observing, and even meteorology have unique tests, like being able to identify rare phenomena like the amazing circumzenithal arc. (You may have spotted one of these “upside-down rainbows” in the past without knowing its true identity!) Let me salute this academic month by offering a few of my favorite sky challenges.

There’s a unique one on September 2. That evening, Jupiter hovers next to the crescent Moon. It should be gorgeous. The problem is, they’re really low and twilight is still bright. If you look west 25 minutes after sunset, the Moon will be only 3° high, slender as a hair, and bright with earthshine. Can you see it? Can you spot Jupiter next to it? If so, give yourself an A for astronomical. If not, use binoculars, which should make it easy if you have a truly unblocked horizon.

Our second test involves vision and sky darkness. It’s not your fault if your eyes are awful or you live in Phoenix. But if you’re away from city lights during the moonless parts of September (the first and last weeks), see how many Pleiades you can count. Average eyesight sees six of the “sisters.” If you can see the seventh faint member, then your keen eyes should observe an eighth, too. Good eyes under dark skies can see all nine that have names. Award yourself 3,100 arbitrary asteroid fragments if you succeed.

In this same faintness category lays an old classic test: glimpsing Uranus with the naked eye. It’s in Pisces, with its exact nightly position findable online, or by using a program like Stellarium. It’s magnitude 5.7 this month, similar to globular cluster M13. Can you see it naked eye? If so, pick up 63 imaginary ether points. (Forget this if you live near Seattle’s bright lights.)

Our next test checks whether you can ascertain a small brightness difference. The star at the point of the V in Taurus is Gamma. The entire V points to a star of similar brightness, and this is Lambda. Now, every four days or a shade less than that, Lambda loses half its light as it’s eclipsed by an unseen companion star. These very cool eclipses are obvious because you merely need to ask yourself: Which is brighter tonight, Gamma or Lambda? If it’s Gamma, then Lambda is in eclipse. Simple! But do those stars show any brightness difference when Lambda shines at full light? Because then, Lambda beats Gamma by only one-third of a magnitude. Discerning that difference is barely doable. You win 98 dark energy units if you can.

“MAYBE WE JUST LOVE CHALLENGES.”

The next test requires a telescope. It involves the outermost ring (the A-ring) of Saturn, which this month forms a striking triangle with orange Mars and orange Antares, the bright star of Scorpius. You can’t miss it. For the first time since 2004, Saturn is so tilted that the edge of the A-ring goes completely around the body of Saturn. It’s not blocked by Saturn’s disk at any point. Can you see this? It’s a bit challenging because Saturn’s body does block the Cassini division between the A and B rings at the far side. Also, Saturn is at quadrature this month, forming its largest angle with Earth and the Sun. This means the ball of Saturn throws its biggest possible shadow upon the rings. Can you see that bit of inky shadow? Bingo: another one billion cosmic fulfillment coins.

The final test involves satellites, which cross the sky every few minutes. Can you tell specifics about each, like its altitude (the slower it is, the higher up), whether it’s still functioning (the answer is no if it blinks on and off, indicating rapid tumbling) and its purpose? (A north-south path means it’s likely a spy satellite.) If yes, you win the Eternally Clear Skies Prize.

Hope these challenges are fun. I’d love to hear some of yours. And just in case you find all tests obnoxious, we won’t do this again for quite a while. Fair enough?