First, some history: It’s known that air grows colder and thinner with altitude, but in 1902 a scientist named Léon Teisserenc de Bort, using instrument-equipped balloons, found a point in Earth’s atmosphere at about 40,000 to 50,000 feet (12,000 to 15,000 meters) where the air stops cooling and begins growing warmer.

He called this invisible turnaround a “tropopause,” and coined the terms “stratosphere” for the atmosphere above, and “troposphere” for the layer below, where we live — terms still used today.

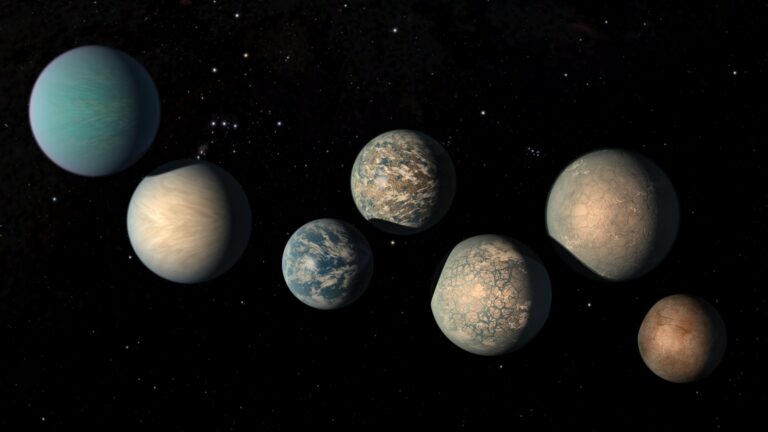

Then, in the 1980s, NASA spacecraft discovered that tropopauses are also present in the atmospheres of the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, as well as Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. And remarkably, these turnaround points all occur at roughly the same level in the atmosphere of each of these different worlds — at a pressure of about 0.1 bar, or about one-tenth of the air pressure at Earth’s surface.

Now, Tyler Robinson and David Catling from UW have used basic physics to show why this happens and suggests that tropopauses are probably common to billions of thick-atmosphere planets and moons throughout the galaxy.

“The explanation lies in the physics of infrared radiation,” said Robinson. Atmospheric gases gain energy by absorbing infrared light from the sunlit surface of a rocky planet or from the deeper parts of the atmosphere of a planet like Jupiter, which has no surface.

Using an analytic model, Catling and Robinson show that at high altitudes atmospheres become transparent to thermal radiation due to the low pressure. Above the level where the pressure is about 0.1 bar, the absorption of visible, or ultraviolet, light causes the atmospheres of the giant planets — and Earth and Titan — to grow warmer as altitude increases.

The physics, they write, provides a rule of thumb — that the pressure is around 0.1 bar at the tropopause turnaround — which should apply to the vast number of planetary atmospheres with stratospheric gases that absorb ultraviolet or visible light.

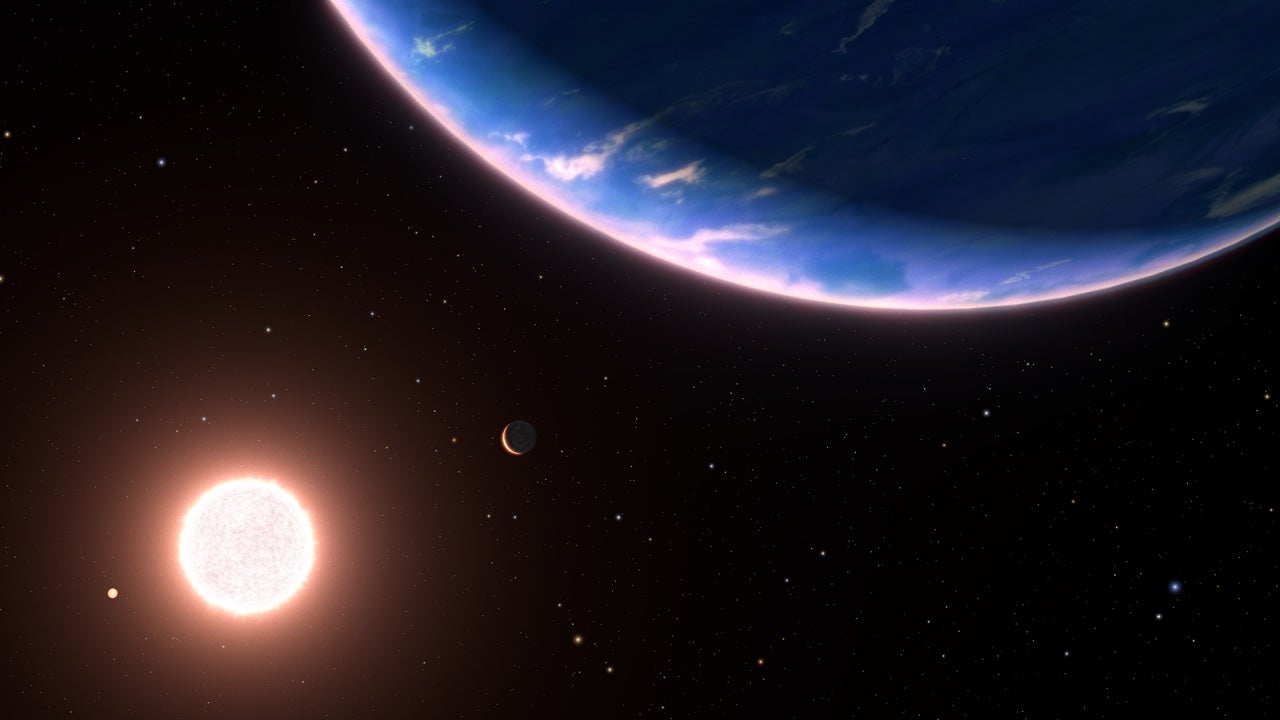

Astronomers could use the finding to extrapolate temperature and pressure conditions on the surface of planets and work out whether the worlds are potentially habitable — the key being whether pressure and temperature conditions allow liquid water on the surface of a rocky planet.

“Then we have somewhere we can start to characterize that world,” Robinson said. “We know that temperatures are going to increase below the tropopause, and we have some models for how we think those temperatures increase — so given that leg up, we can start to extrapolate downward toward the surface.”

“It’s neat that common physics not only explains what’s going on in solar system atmospheres, but also might help with the search for life elsewhere,” Robinson said.