Can a black hole form without a parent star?

A few different kinds of black holes exist. First are stellar-mass black holes, which can range from 3.3 to 100 times the mass of the Sun. These are the lowest-mass black holes that we’ve observed. One way these black holes form is when the most massive stars in the universe reach the end of their life. Alternatively, a neutron star can become a black hole if it either accretes enough material from a companion star or merges with another star, pushing it over the neutron star mass limit.

But stellar-mass black holes are on the low-mass side of the spectrum. On the heavier side are supermassive black holes. These heavyweights lie at the hearts of most galaxies and weigh millions to billions of solar masses. Between them lie intermediate-mass black holes — ranging from 100 to 1 million solar masses.

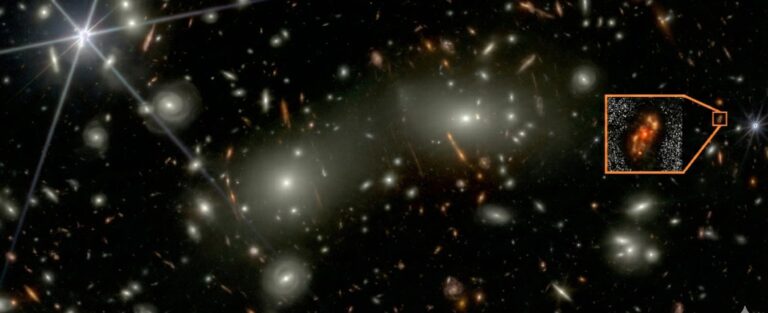

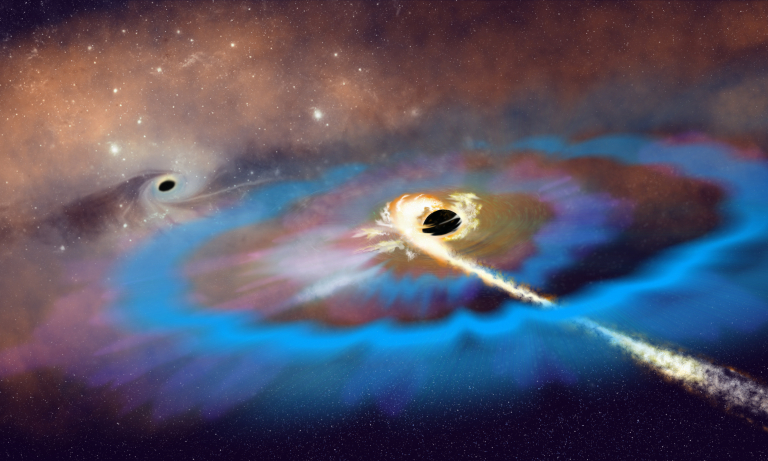

Although researchers have the basic formation of stellar-mass black holes down, supermassive black holes have posed a problem because scientists don’t yet understand how they grew so big so fast in the early universe. While it’s true that stellar-mass black holes could merge and create a supermassive one, there just isn’t enough time for stars to die in great enough amounts to account for the behemoths seen in the cosmos’ early galaxies.

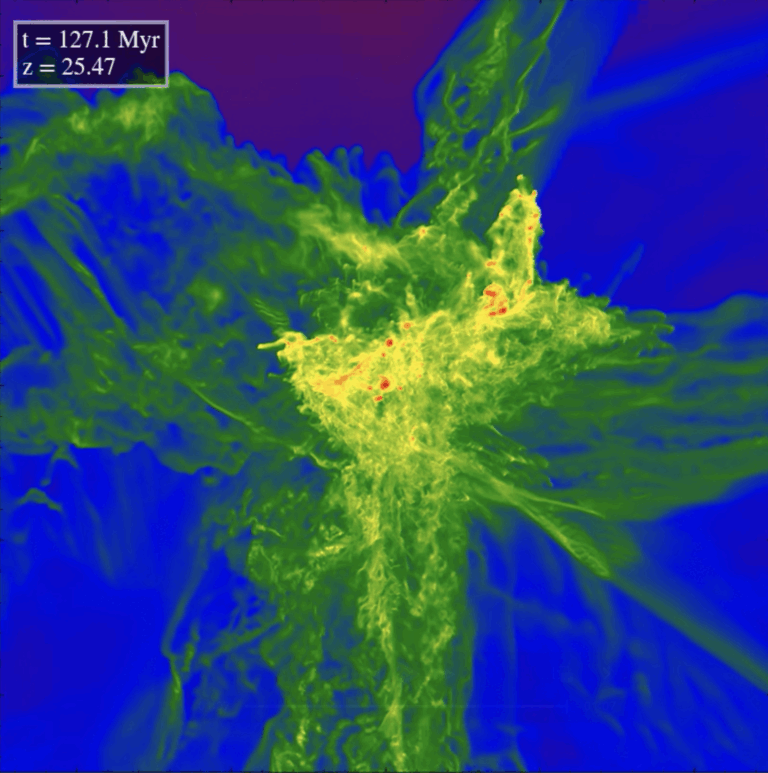

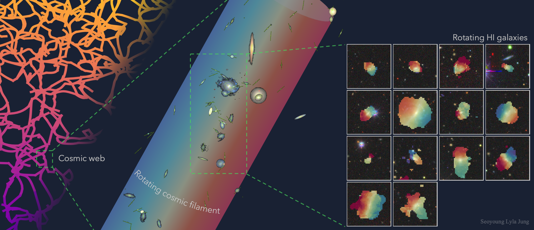

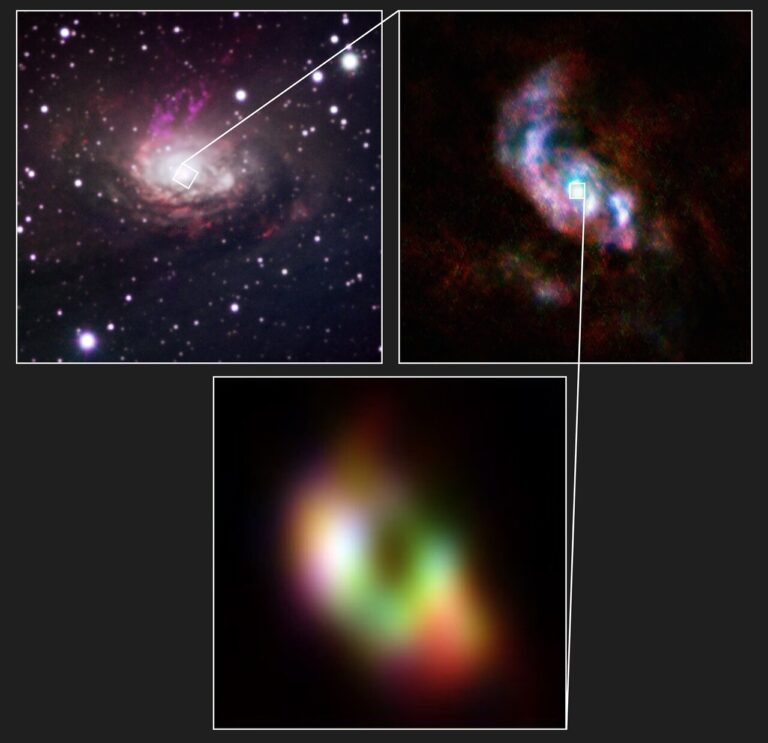

But there is a starless route that could lead to these monsters, one that was only possible in the early universe. So-called direct-collapse black holes wouldn’t need to wait for a star to die to form them. Instead, clusters of early galaxies could influence each other. If you have two or more early galaxies near each other, one may undergo rapid star formation. This heats up the gas within a neighboring galaxy, preventing that gas from fragmenting into clumps that would eventually become stars. This monolith of gas is then overcome by gravity and collapses into an intermediate-mass black hole. Such events could occur throughout the young galaxy, forming a few intermediate-mass black holes that eventually coalesce at the center of the galaxy, creating a supermassive black hole.