Michael E. Bakich

Modern star atlases are the amateur astronomer’s guides to the stars. In Phil Harrington’s review of star atlases, a number of excellent beginner, intermediate, and advanced atlases are listed. But star atlases have a long and storied history. Prior to the twentieth century, most star atlases were designed to look good as well as to guide observers through the sky. In this short look, I’ve listed nine examples of earlier star atlas entries.

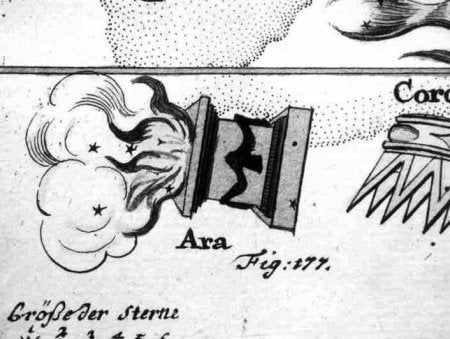

Ara the Altar

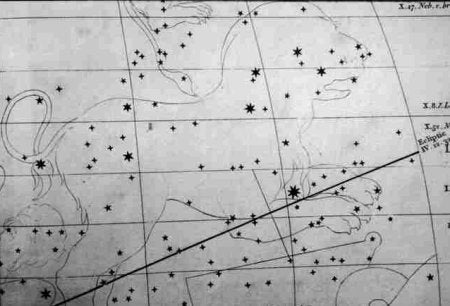

by Johann Leonhard Rost, from Atlas Portatilis Coelestis, Nuremburg, 1793.

Rost’s modest star atlas demonstrated reasonable accuracy and displayed many constellations. Ara the Altar is a small, southern-hemisphere constellation located under the tail of Scorpius. Ara is completely invisible for observers living at latitudes above 45° north. The nearest globular cluster to us — NGC 6397 — may be found in Ara. This magnitude 7.5 object lies at a distance of only 8,400 light-years.

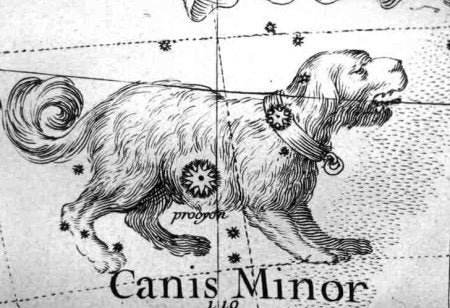

by Ignace Gaston Pardies, from Globi Coelestis in Tabulas Planas Redacti Descriptio, Opus posthumus, Paris, 1674.

The star atlas published by Pardies drew heavily on Bayer’s Uranometria for inspiration. Even so, it has been called one of the most stylistically attractive ever published. Here we see Canis Minor the Lesser Dog, a small but easily viewed constellation best seen in the winter sky in the Northern Hemisphere. Its brightest star, Procyon, is the 8th brightest star in the night sky. At least some part of this constellation is visible anywhere in the world, and it is completely visible from latitudes north of -70°.

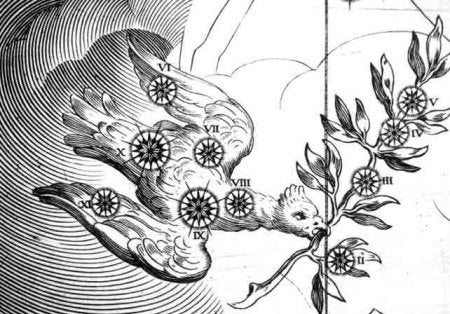

by Julius Schiller from Coelum Stellatum Christianum, Augsburg, 1627.

Schiller’s star atlas, which translates as “Christian Starry Heavens” was set up exactly as Bayer’s Uranometria, although the plates are a bit smaller. Schiller replaced the traditional constellations with Christian counterparts. Columba the Dove, pictured here, is the only surviving constellation named after an object in the Bible. Columba represents the dove that Noah sent out to test whether the waters from the Great Flood had receded. The point in the sky away from which our Sun seems to be heading, known as the solar antapex, lies within the boundaries of this constellation.

by Johann Elert Bode, from Uranographia Sive Astrorum Descriptio, Berlin, 1801.

One of the finest star atlases ever produced appeared in the first year of the 19th century. Bode’s atlas, though large and expensive, was an immediate sensation. This illustration from the atlas shows Crux the Southern Cross, the smallest of the 88 constellations. It is completely invisible for observers north of latitude +35°. Despite its size (or perhaps because of it), Crux is the brightest constellation. Three of the twenty-five brightest stars lie in Crux. Early European explorers formed this constellation. The first reliable reference we have about Crux comes from a letter written by the Italian navigator Amerigo Vespucci, in 1503. Crux was important to early navigators because a line drawn from two of its stars (Gamma Crucis through Alpha Crucis) and extended 25° roughly points to the south celestial pole.

by Elijah Hinsdale Burritt from Atlas Designed to Illustrate the Geography of the Heavens, Hartford, 1835.

Not all star atlases depict the constellations as florid figures overflowing with detail. Wollaston’s atlas, which appeared in the early part of the 19th century, shows a very simple figure: Leo the Lion, well known as being one of the constellations of the zodiac. Its two main parts, the “sickle” and a triangle of stars, do suggest the shape of a reclining lion. Leo contains four stars ranked in the top 100 by brightness. Leo’s brightest star, Regulus, was one of the four Royal Stars of the ancient Persians.

by Francis Wollaston, from A Portrature of the Heavens, as They Appear to the Naked Eye, London, 1811.

Not all star atlases depict the constellations as florid figures overflowing with detail. Wollaston’s atlas, which appeared in the early part of the 19th century, shows a very simple figure: Leo the Lion, well known as being one of the constellations of the zodiac. Its two main parts, the “sickle” and a triangle of stars, do suggest the shape of a reclining lion. Leo contains 4 stars ranked in the top 100 by brightness. Leo’s brightest star, Regulus, was one of the four Royal Stars of the ancient Persians.

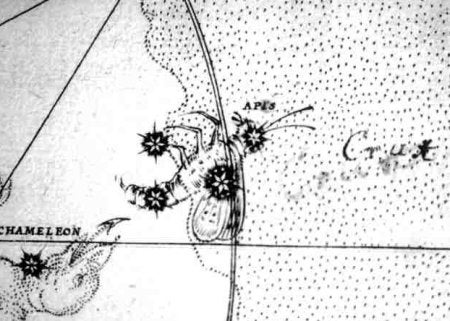

by Johann Bayer from Uranometria, Augsburg, 1603.

Of all star atlases, the most famous is probably Bayer’s Uranometria, which appeared in 1603. Bayer was the first to use Greek letters to designate stars in constellations. In all but a few cases he labeled the brightest star in the constellation Alpha (the first Greek letter). This was followed by Beta (second brightest), Gamma (third brightest), and so on. In the case of 11 constellations, Bayer’s atlas represents the earliest existing picture of each. For example, Musca the Fly (labeled “Apis” on this chart) was a southern constellation invented by two Dutch navigators, Pieter Dirksz Keyser and Frederick de Houtman, during a three-year voyage they took beginning in 1595. Musca first appeared on a celestial globe by Petrus Plancius, but that globe has not survived.

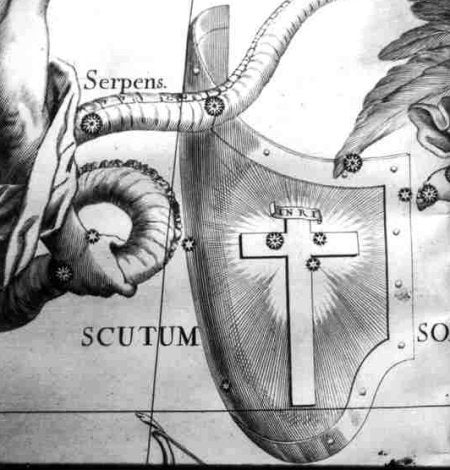

by Johannes Hevelius, from Firmamentum Sobiescianum, sive Uranographia, totum Coelum Stellaatum, Gdansk, 1690.

Hevelius’s Firmamentum, which appeared in 1690, was the first star atlas to rival Bayer’s Uranometria in scope, accuracy, and usefulness. It differs from the other atlases pictured here because Hevelius chose to picture the constellations as they would be seen from the outside of a celestial globe. This image shows Scutum the Shield, one of seven constellations still in use invented by Hevelius. Scutum is a tiny constellation that is completely visible for anyone living south of latitude +74°.

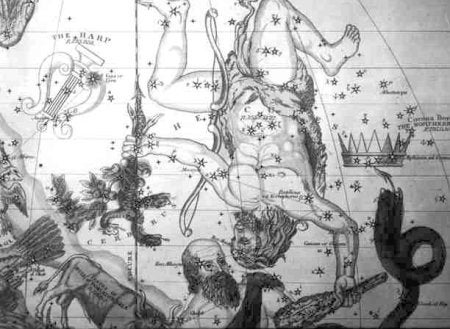

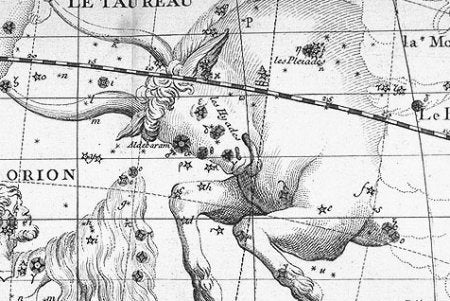

by John Flamsteed from Atlas Coelestis, London, 1729.

This image from Flamsteed’s atlas represents the last of the five grand star atlases (along with Bayer, Hevelius, Schiller, and Bode). The zodiacal constellation Taurus the Bull is shown. Though considered a northern constellation, Taurus is completely visible from latitudes north of -59°. The brightest cluster in the sky, the Pleiades (M45), also known as the Seven Sisters, lies within the boundaries of Taurus. Two thousand years ago and earlier, the Pleiades was considered a distinct constellation.