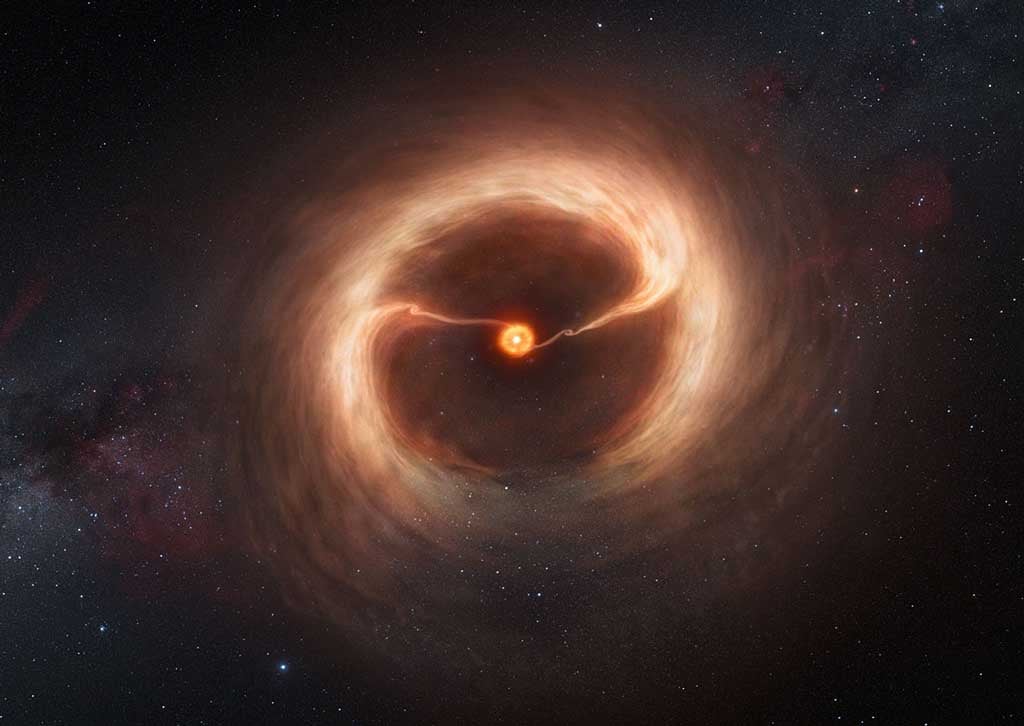

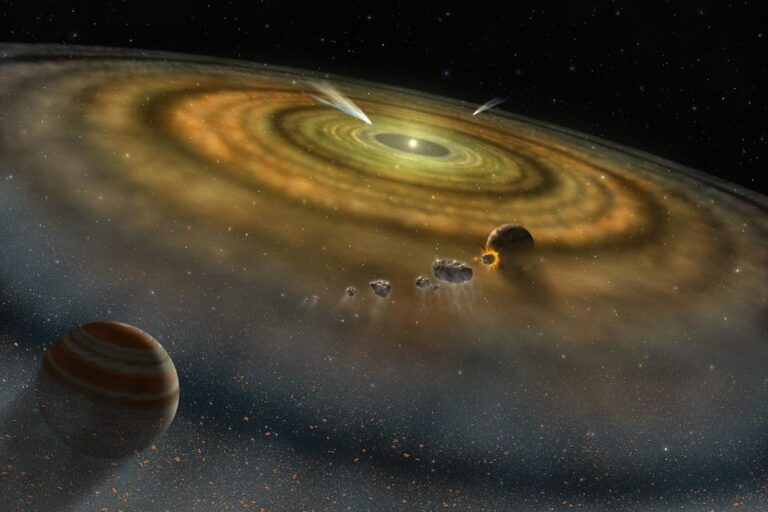

The international team of astronomers studied the young star HD 142527, more than 450 light-years from Earth, which is surrounded by a disk of gas and cosmic dust — the remains of the cloud from which the star formed. A gap, which is thought to have been carved by newly forming gas giant planets clearing out their orbits as they circle the star divides the dusty disk into an inner and an outer part. The inner disk reaches from the star out to the equivalent of the orbit of Saturn in the solar system, while the outer disk begins about 14 times farther out. The outer disk does not surround the star uniformly; instead, it has a horseshoe shape, probably a result of the gravitational effect of orbiting giant planets.

According to theory, the giant planets grow by capturing gas from the outer disk in streams that form bridges across the gap in the disk.

“Astronomers have been predicting that these streams must exist, but this is the first time we’ve been able to see them directly,” said Simon Casassus from the University of Chile. “Thanks to the new ALMA telescope, we’ve been able to get direct observations to illuminate current theories of how planets are formed.”

Casassus and his team used ALMA to look at the gas and cosmic dust around the star, seeing finer details and closer to the star than could be seen with previous such telescopes. ALMA’s observations, at submillimeter wavelengths, are also impervious to the glare from the star that affects infrared or visible-light telescopes. The gap in the dusty disk was already known, but they also discovered diffuse gas remaining in the gap and two denser streams of gas flowing from the outer disk across the gap to the inner disk.

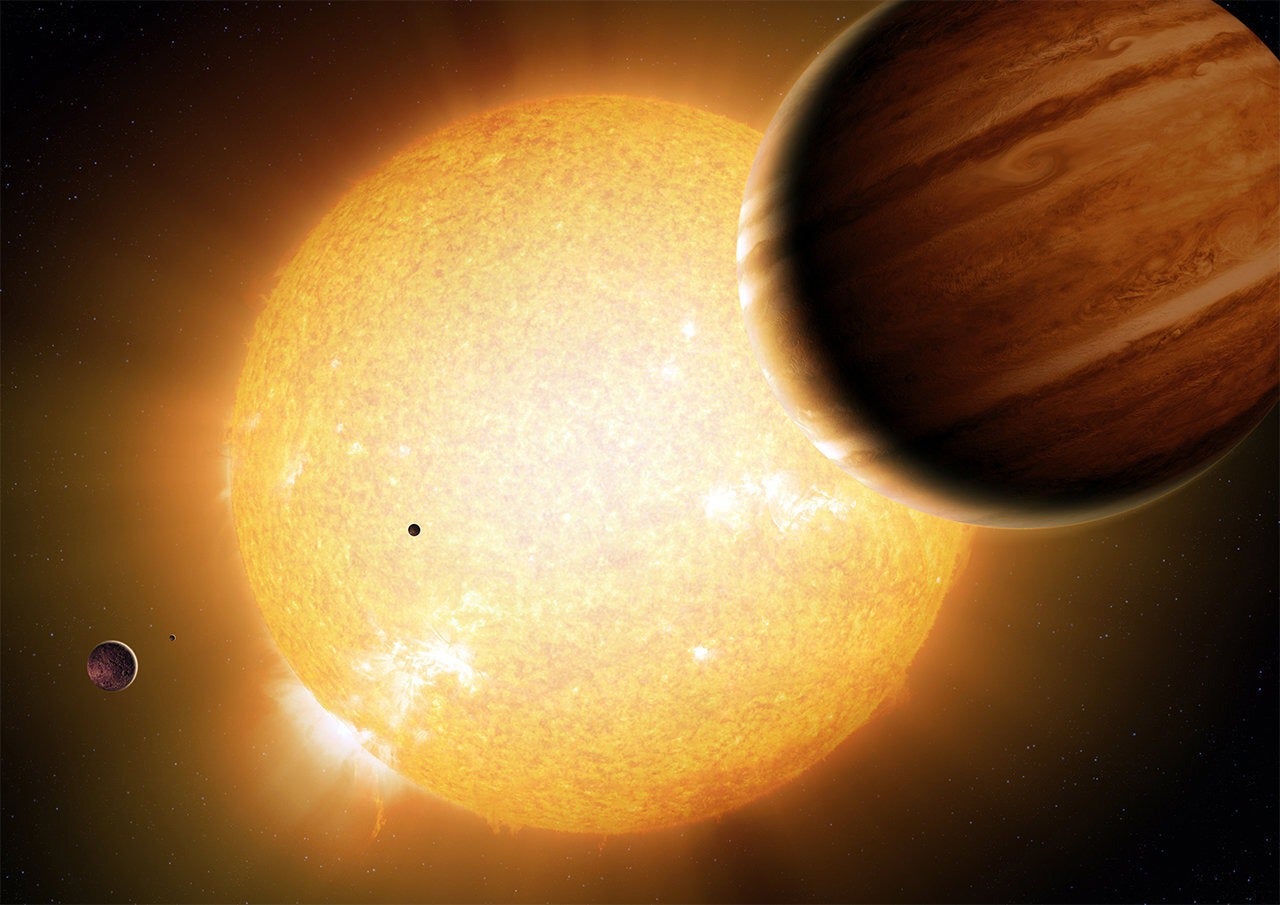

“We think that there is a giant planet hidden within and causing each of these streams,” said Sebastian Perez from the University of Chile. “The planets grow by capturing some of the gas from the outer disk, but they are really messy eaters; the rest of it overshoots and feeds into the inner disk around the star.”

The observations answer another question about the disk around HD 142527. As the central star is still forming by capturing material from the inner disk, the inner disk would have already been devoured if it was not somehow topped up. The team found that the rate at which leftover gas streams onto the inner disk is just right to keep the inner disk replenished and to feed the growing star.

Another first is the detection of the diffuse gas in the gap. “Astronomers have been looking for this gas for a long time, but so far we only had indirect evidence for it,” said Gerrit van der Plas from the University of Chile. “Now, with ALMA, we can see it directly.”

This residual gas is more evidence that the streams are caused by giant planets, rather than even larger objects such as a companion star. “A second star would have cleared out the gap more, leaving no residual gas,” said Perez. “By studying the amount of gas left, we may be able to pin down the masses of the objects doing the clearing.”

What about the planets themselves? Casassus explains that, although the team did not detect them directly, he is not surprised: “We searched for the planets themselves with state-of-the-art infrared instruments on other telescopes. However, we expect that these forming planets are still deeply embedded in the streams of gas, which are almost opaque. Therefore, there may be little chance of spotting the planets directly.”

Nevertheless, the astronomers aim to find out more about the suspected planets by studying the gas streams as well as the diffuse gas. The ALMA telescope is still under construction and has not yet reached its full capabilities. When it is complete, its vision will be even sharper, and new observations of the streams may allow the team to determine properties of the planets, including their masses.