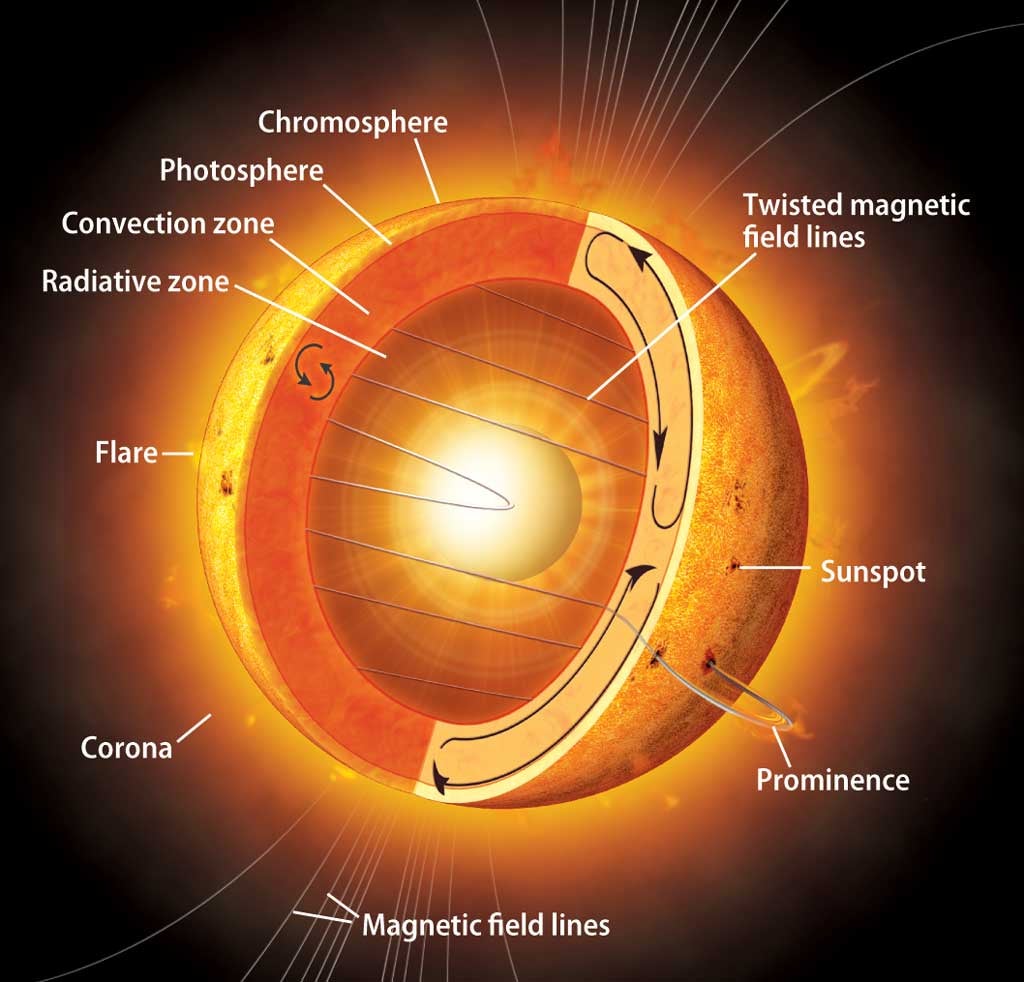

The Sun’s radiative interior extends to about two-thirds of the solar radius and is the source of our star’s rotation; photons and other particles carry heat in this region of the solar interior. This, in turn, feeds convection, which stirs the plasma under the Sun’s visible surface (called the photosphere). The interaction between convection and rotation in the upper third of the Sun’s interior creates strong magnetic fields, which rise through the interior and thread through the surface, making sunspots, prominences, and all kinds of beautiful structures.We think the balance between the pressures (or forces) of magnetism and convective plasma motion is critical in heating the Sun’s outermost atmospheric layer, the corona. In our star’s interior, the pressures of plasma motions are typically much larger than those exerted by the magnetic field; in the corona, however, the opposite is true, and the magnetic field dominates the plasma motions. Just above the Sun’s surface is a layer called the chromosphere where these forces nearly balance each other. In that “transition” layer, plasma motions can drive magnetic fields, and vice versa.

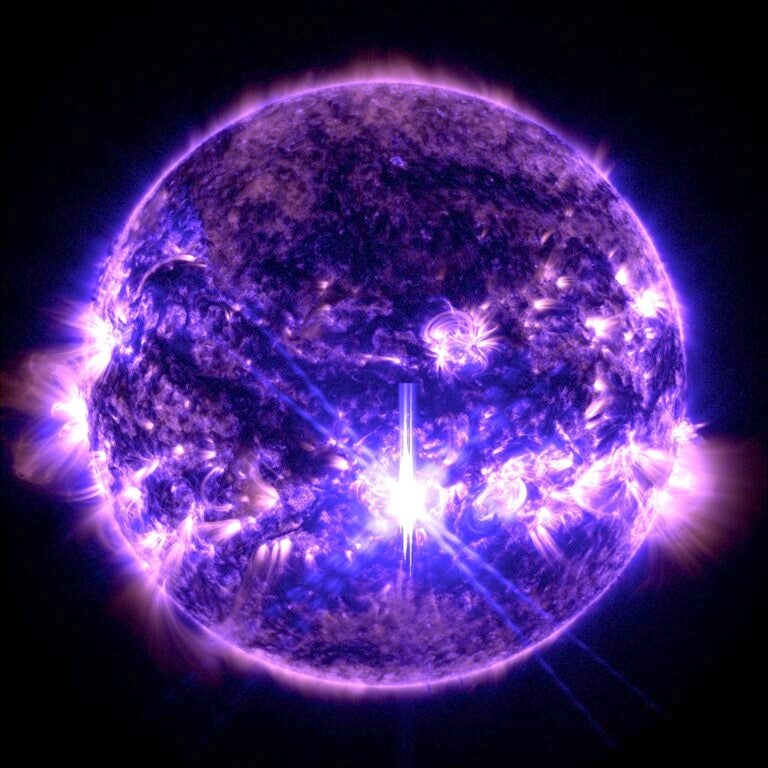

The Solar Dynamics Observatory and Hinode have given us clearer-than-ever observations that show rapid heating events like fast jets of hot material triggered in or just above the chromosphere. The convection within the Sun generates small but violent changes to the magnetic field, which then create these jets. We see in these jets some portion of the hot plasma that fills the coronal loops — one component of the coronal heater.

Another likely component of the heater comes in the form of magnetic (or Alfvén) waves. The convective motions also generate these waves, which “ride” on the same hot jets and roar into the corona at even higher speeds. The Alfvén waves likely dump their energy in the corona, too, but the means by which that happens is a topic of great debate. So, we still don’t know exactly why the Sun’s corona is hot, but we are finding some of the components of the system. This helps us considerably in trying to understand how the complete coronal heater works.

Scott McIntosh

National Center for Atmospheric Research,

Boulder, Colorado