Key Takeaways:

- September offers various celestial events, including Saturn and Neptune's oppositions, Mars's approach to solar conjunction, and favorable viewing of Uranus and Jupiter.

- Multiple transits of Saturn's moons, particularly Titan, are predicted for September, including shadow transits visible from the U.S. on September 3/4 and 19/20. Titan's occultations by Saturn are also noted.

- Close conjunctions are highlighted: Venus with M44 (Beehive cluster) early in the month, then with Regulus and the crescent Moon near the end of September; Saturn and Neptune remain in close proximity throughout the month.

- Observational opportunities for other celestial objects are detailed, including Jupiter's Galilean moons transits, Uranus's visibility near the Pleiades, and the comet C/2024 E1 Wierzchoś and asteroid 4 Vesta.

September’s sky is rich with opportunities. Titan’s shadow continues to transit Saturn. The ringed planet reaches opposition along with Neptune, with both worlds in the same region of the sky. Mars is descending toward solar conjunction. Uranus is a fine binocular target, while Jupiter dominates the early morning. Venus starts the month near M44, then inches closer to a conjunction with Regulus and the crescent Moon.

Mars continues its long slide toward solar conjunction in early 2026 and is visible low in the west after sunset. It shines at magnitude 1.6 in Virgo. On Sept. 11, Mars is 2.4° north of Spica, which shines at magnitude 1.0. Both star and planet set before 9 p.m. local daylight time, and you’ll need a clear western horizon to spot them. Mars is too small to see any appreciable detail visually.

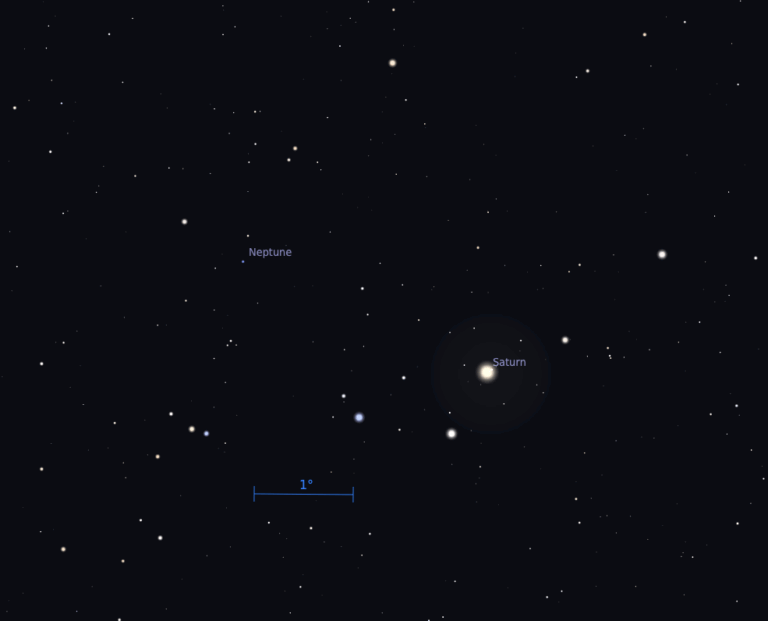

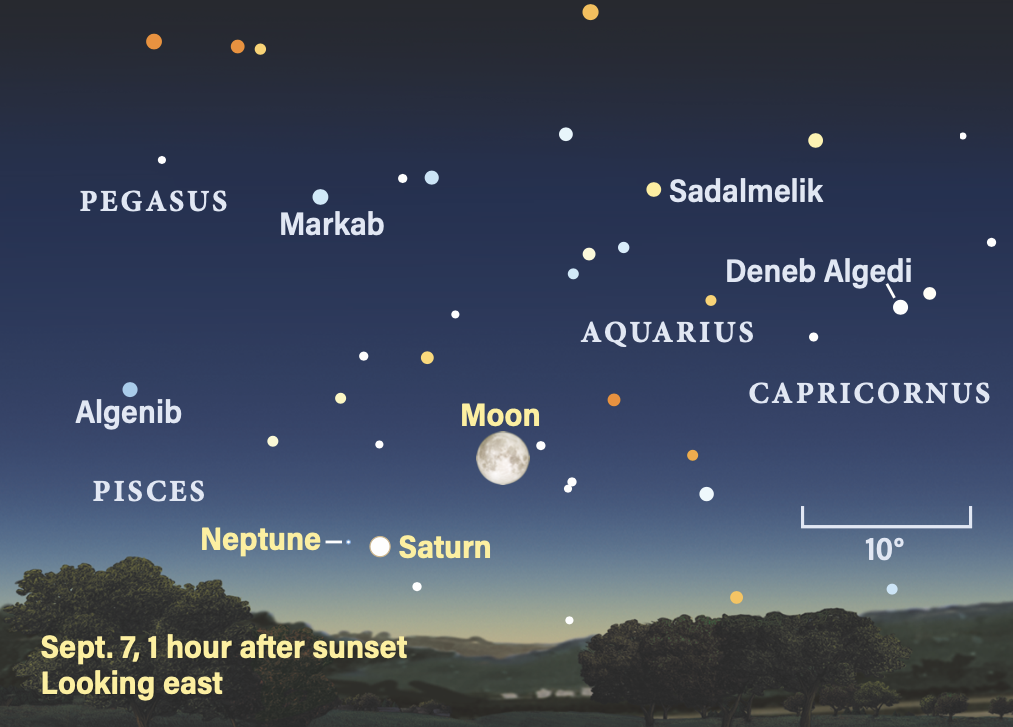

Neptune and Saturn remain near each other in the sky. They rise before 9 p.m. local daylight time in early September and by 6:30 p.m. on the 30th. Both reach opposition this month.

Saturn, in Pisces, moves toward Aquarius, arriving the 29th. There are a half-dozen 5th-and 6th-magnitude stars in the vicinity, making a great view in binoculars. The Sept. 7 Full Moon rises half an hour before Saturn, with 9° between them.

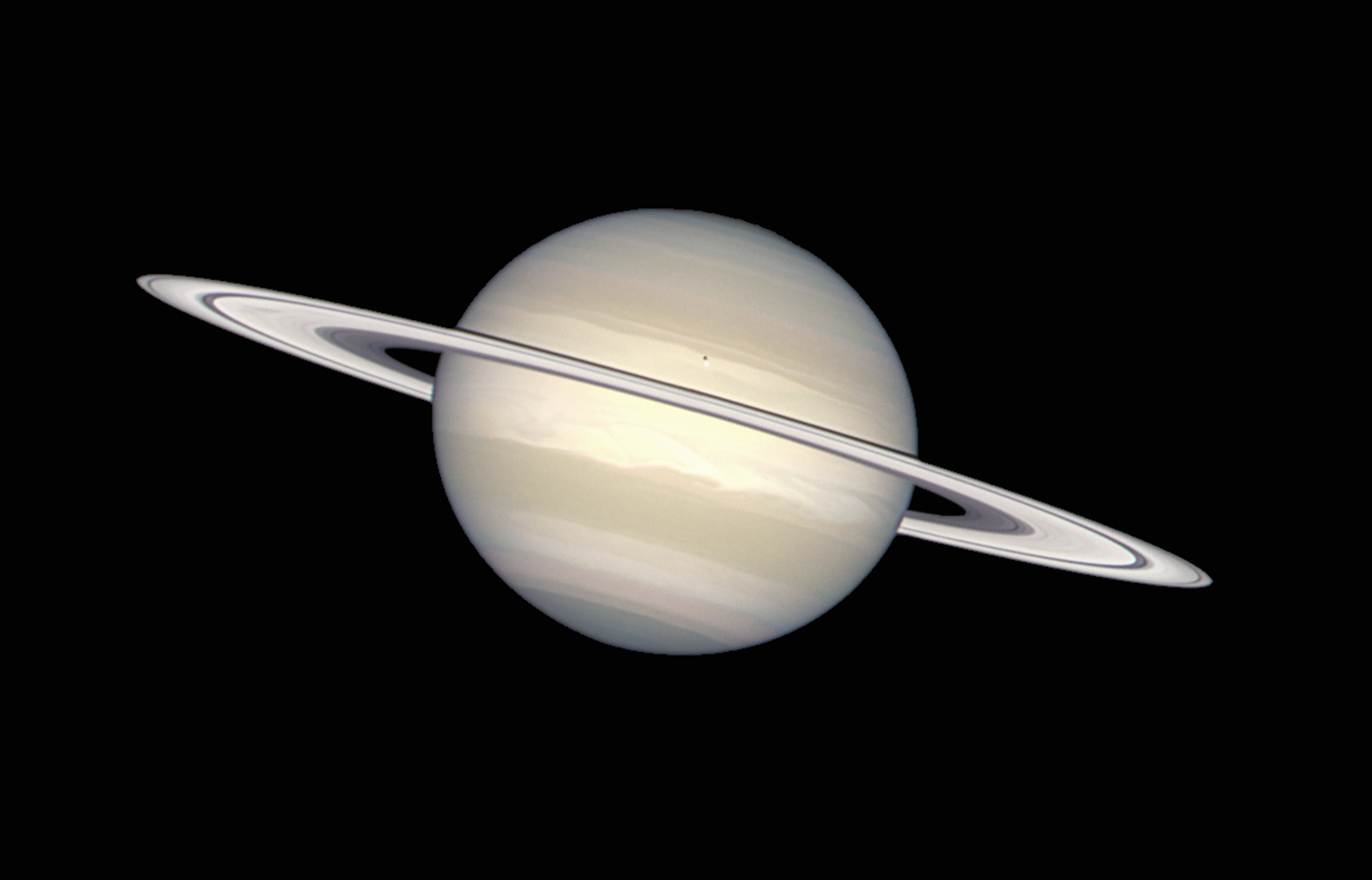

Saturn shines at magnitude 0.6 and reaches opposition Sept. 21. This is the closest it gets to Earth: 794.8 million miles away. In a telescope the disk spans 19″, while the narrow rings, tilted by only 2° to our line of sight, span 44″. Their low tilt offers a broad view of both hemispheres of the planet.

Five of Saturn’s moons are relatively easy to track: Titan, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and Iapetus. Titan is brightest (magnitude 8.5) and visible through any small telescope. It circles the ringed planet every 16 days.

We now see the major moons transit the face of Saturn. Most are too small to view easily, but Titan casts an obvious black dot on the disk, visible in most telescopes. There are two transits visible from the U.S. this month.

The first occurs Sept. 3/4 at 1 a.m. EDT (early on the 4th in the Eastern and Central time zones). It takes about 25 minutes for the full shadow to appear. You should notice a distinct notch forming at Saturn’s northeastern limb by 1:12 a.m. EDT. Local conditions will affect how well you see ingress. Notice how far Titan is from the limb. We are still more than two weeks from opposition.

The shadow reaches the midpoint of the disk around 3 a.m. EDT; just under two hours later, Titan begins a transit across the northern polar region. The moon stands partially in front of Saturn’s north pole at 5 a.m. EDT, shortly after its shadow began its egress.

The shadow is fully gone by 5:15 a.m. EDT and Titan’s transit ends by 5:30 a.m. EDT. (Planetary imagers, note that Tethys and its shadow transit between about 4:30 a.m. EDT and 6:25 a.m. CDT, with the transit ending in twilight across the Midwest. The tiny shadow is unlikely to be visible through most telescopes.)

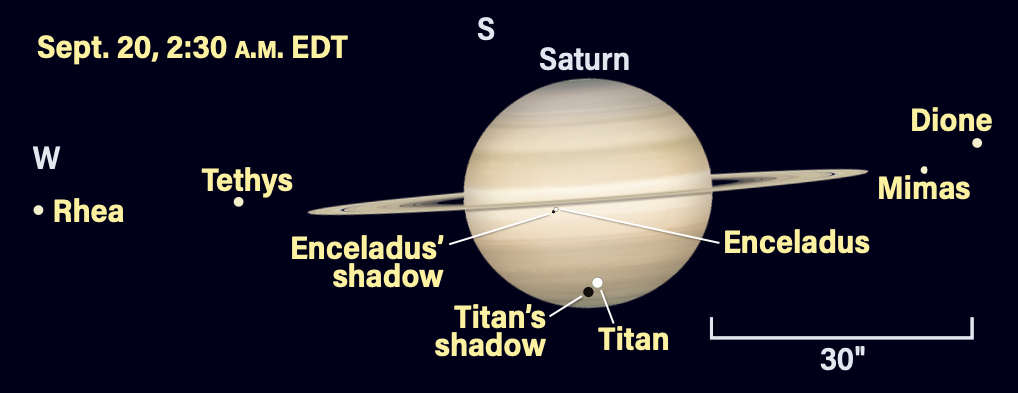

A second Titan transit occurs Sept. 19/20, just one day from opposition. Now Titan and its shadow almost overlap! Titan’s transit begins at the northwestern limb of Saturn at 12:33 a.m. EDT. The shadow’s ingress begins about two minutes later, although it will be difficult to tell them apart due to atmospheric conditions blurring the view. The dark notch of the shadow should be visible by 12:45 a.m. EDT. Titan is fully on Saturn’s disk by 1:02 a.m. EDT.

Titan and its shadow, just arcseconds apart, travel across the northern polar region of Saturn. They’re midway around 2:30 a.m. EDT. The shadow reaches the northwestern limb of Saturn just before 3:30 a.m. EDT and leaves by 4:05 a.m. EDT Titan remains fully on the disk another three to four minutes and exits fully by 4:37 a.m. EDT.

Titan is also occulted by Saturn. Late on Sept. 11, Titan enters Saturn’s shadow just beyond the southwestern limb. Watch closely as it begins fading at about 11:10 p.m. EDT; it’s midway into the eclipse seven minutes later. The moon has disappeared by 11:33 p.m. EDT. Between 3:30 a.m. and 4:05 a.m. EDT on the 12th, Titan reappears from behind the southeastern limb.

Spot Titan again disappearing at the southwestern limb of Saturn Sept. 27, starting soon after 9:30 p.m. EDT (not visible in the Pacific time zone). The moon’s reappearance at the southeastern limb begins around 2:07 a.m. EDT (now the 28th for some) and it is clear of the limb 27 minutes later.

Tenth-magnitude Tethys and Dione cross Saturn’s disk the morning of opposition, Sept. 21. Dione leads around 4:03 a.m. EDT; Tethys follows less than five minutes later. Around 5:30 a.m. EDT, both moons lie roughly in the middle of the disk, just north of the rings.

On Sept. 1, Iapetus is two days past its brighter western elongation, 9′ west of Saturn. Iapetus then fades to 11th magnitude as it approaches superior conjunction on the 18th, when it is only 1.3′ due south of the planet. By Sept. 30, Iapetus reaches 8′ east of Saturn and is nearing 12th magnitude.

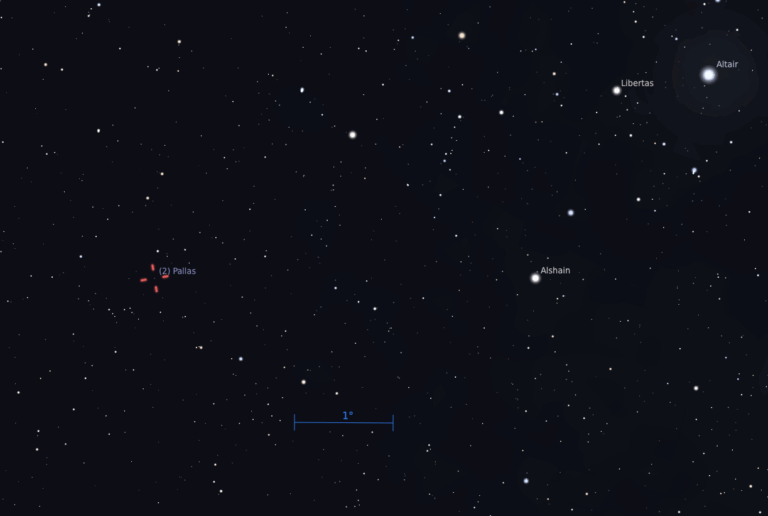

Neptune remains together with Saturn within the field of view of binoculars, starting September 1.7° northeast of the ringed planet and ending the month 3° away. Saturn’s motion causes the change — Neptune is so far that its own retrograde motion is barely perceptible.

Neptune shines at magnitude 7.7 and reaches opposition on the 23rd, two days after Saturn. On the 9th, the bluish planet stands a Moon’s width south of a 6th-magnitude field star. It should be easy to spot. Simply center Saturn in a pair of binoculars, move northeast about half a field, and Neptune will be near the center of your view.

Uranus rises about an hour before midnight on Sept. 1 and is roughly 4.5° south-southeast of the Pleiades (M45). It reaches a stationary point Sept. 6 and moves westward the rest of the month. It shines at magnitude 5.7, an easy binocular object.

Uranus forms the base of a triangle together with 4th-magnitude 37 Tauri, which stands 3° northeast of Uranus and 4.5° southeast of M45 (the triangle’s apex). The 4″-wide planetary disk is visible through a telescope. By the end of September, Uranus rises around 9 p.m. local daylight time and is 30° high in the east at midnight.

Jupiter is up in the east by 3 a.m. local daylight time on Sept. 1. Its northern declination affects rising times significantly, depending on your latitude. It’s visible a few hours earlier by the end of September.

Jupiter dominates the constellation Gemini at magnitude –2.0. Atmospheric details are obvious through a telescope. Its disk spans 34″, growing to 37″ during the month.

Three of the Galilean moons — Io, Europa, and Ganymede — orbit in a 4:2:1 resonance. This causes simultaneous transits to repeat. The action begins Sept. 20 as Io and Europa transit, underway as Jupiter rises along the East Coast. The low altitude makes observation difficult. Seven days later, on Sept. 27, Io and Europa again cross the disk with their shadows as the planet rises. By 12:59 a.m. EDT, Io’s shadow is noticeable on the eastern limb, with Europa’s shadow near the western limb. Twenty-five minutes later, Europa begins its transit. Europa’s shadow leaves the disk at 1:40 a.m. EDT.

Io begins to transit at 2:09 a.m. EDT; its shadow leaves the disk 61 minutes later. Europa’s transit ends at 4:14 a.m. EDT, and Io follows nine minutes later. But it’s not over yet: Io catches up with Europa and passes partially behind it between about 4:49 a.m. and 5:09 a.m. EDT.

Ganymede’s shadow is transiting Sept. 7 as Jupiter rises in the Midwest. The shadow leaves Jupiter beginning at 5:33 a.m. EDT and takes about 10 minutes to exit. Ganymede itself is near the southeastern limb, reaching it at 5:55 a.m. CDT. West Coast observers will see Ganymede in the middle of the disk roughly an hour before sunrise.

Io and its shadow transit Sept. 18 after Ganymede reappears from occultation (egress at 4:17 a.m. EDT is visible from the Eastern and Central time zones). Io’s shadow appears at 4:34 a.m. EDT and Io itself begins a transit at 5:44 a.m. EDT.

Venus rises just before 4 a.m. local daylight time Sept. 1, shining at magnitude –3.9. Rising more than 2.6 hours before the Sun, Venus is visible in the eastern sky. It stands some 20° high at 6 a.m. local daylight time.

Don’t miss the binocular view on this morning with the Beehive star cluster (M44) just 1° north of the planet. It’s also stunning in a low-power scope.

On this day, Venus displays a 84-percent-lit disk 12″ wide. By the end of September, the phase has expanded to 91 percent and the disk shrunk to 11″, owing to increasing distance from Earth.

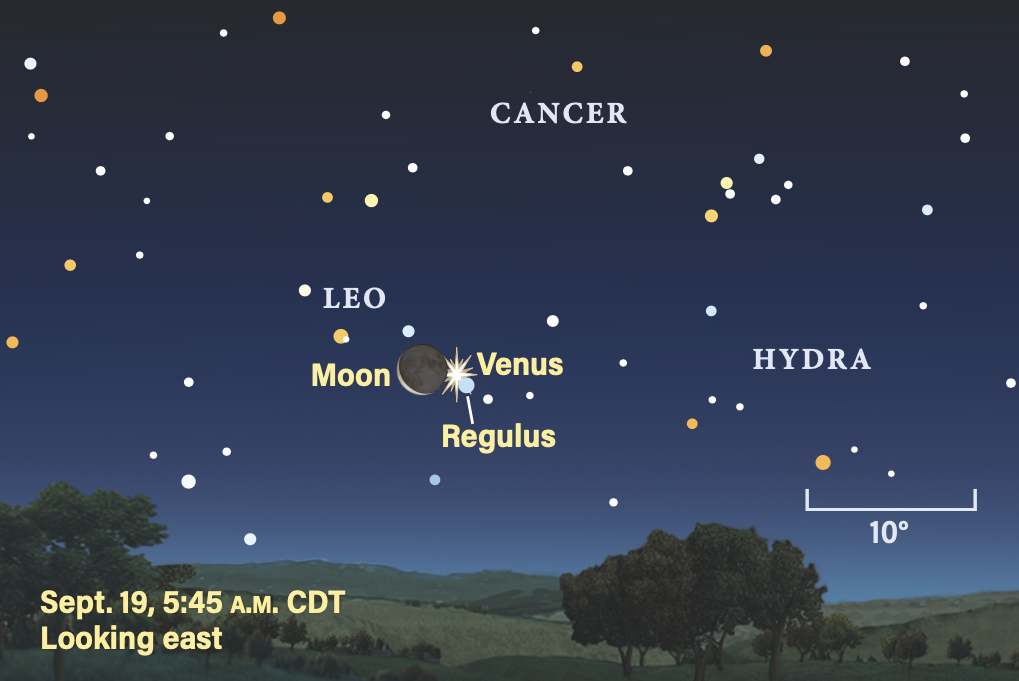

Venus moves east into Leo by Sept. 10 and reaches a wonderful event Sept. 19, when the brilliant planet stands one Moon’s width due north of Regulus.

The waning crescent Moon is also very close; its position depends on your time zone and latitude. Observers in the northeastern U.S. see the Moon about 1° northwest of Venus at 4:30 a.m. EDT, moving to a position about 0.5° due north of Venus just before sunrise. Venus is occulted by the Moon from Northern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, and Europe.

Kansas City sees the Moon, Venus, and Regulus in a straight line shortly after rising, the Moon still 0.5° north of Venus. Within an hour, the Moon moves northeast of the planet. As the trio rises farther west, the Moon stands a greater distance northeast of Venus.

Mercury is a challenge, rising an hour before the Sun on Sept. 1. It shines at magnitude –1.3 and stands 2.5° northwest of Regulus, also challenging in twilight. On the 2nd, Mercury is 1.2° due north of Regulus. The planet quickly drops out of view and reaches superior conjunction with the Sun on the 13th. It will reappear low in the evening sky by October.

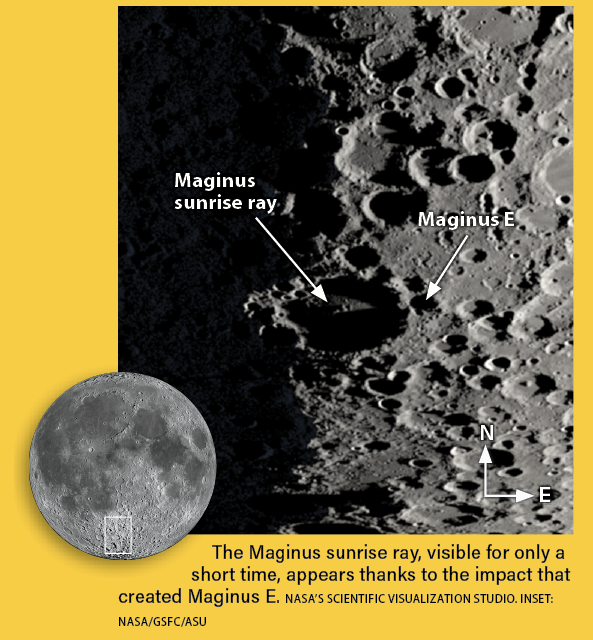

Rising Moon: The Maginus sunrise ray

As if piercing a crater wall, the rising Sun first lights up the central peaks of Maginus. Within 60 minutes, the light spreads into a long and narrow torch splitting the 100-mile-wide bowl into two dark halves. Over the following two hours, the Maginus sunrise ray spreads into a wider triangular beam.

The First Quarter Moon on Sept. 29 has the specific orientation to show off the ray to most of North America. If it is cloudy, give it another try on Nov. 27. The impact that created Maginus E to the east was big enough to blow through the wall, which lets the rising Sun shine through. You’d think this story would be common enough across the Moon’s face, but there are very few hits that are both large enough and facing due east.

The unwrapping of this gift is so gradual that there’s time to take your viewing party on a tour up the terminator. Is the sky steady enough to see the rille in the Alpine Valley? Get back to Maginus to note any change, then soak in the toothy black shadows cast into Archimedes. After another examination of the sunrise ray, jump to Plato, then have a final look at the cone of light on the crater floor before the Moon gets too low.

Maginus is named for Giovanni Antonio Magini, Italian mathematician and astrologer. He died in 1617 — might he have looked through Galileo’s telescope before then?

Meteor Watch: Looking for light in the lull

No major meteor showers are active in September, so we enter a bit of a lull after the excitement of August.

Meteoritic dust from thousands of comets passing over the eons is visible before dawn as the zodiacal light, as sunlight reflecting off the dust creates a faint glow. You’ll need a very dark eastern horizon with no streetlights nearby; higher elevations get a better view, too.

The zodiacal light appears as a faint cone-shaped glow aligned with the ecliptic. On September mornings well before dawn, the high angle of the ecliptic benefits views of it. The broad base of the glow is in Leo as that constellation rises, and narrows higher in the sky through Cancer and Gemini. Catch it on moonless nights in the third and fourth week of September for the darkest skies.

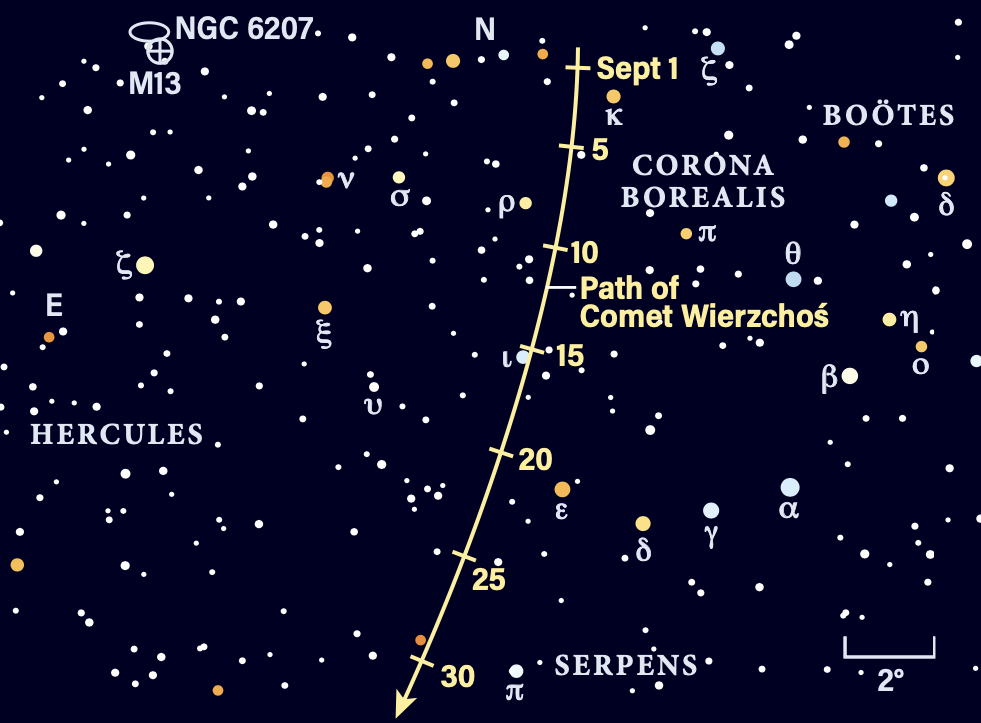

Comet Search: Brightening prospects

C/2024 E1 Wierzchoś ends the months of drought, chaseable with an 8-inch scope as long as you’re out under dark country skies. There’s no evening rush because it floats high to the west in Corona Borealis.

The easiest nights to find Wierzchoś are the 15th and 16th, when it lies half a degree from Iota (ι) Coronae Borealis, the last (easternmost) jewel in the Northern Crown. Dropping inside the orbits of main-belt asteroids, the small comet is just waking up, its coma of dust only a couple arcminutes across and barely out of round, mimicking an elliptical galaxy. Use 150x or more to study its shape and compare it to the spiral galaxy NGC 6207, which flanks M13.

This classic Oort Cloud object was picked up by Kacper Wierzchoś working at Arizona’s Mount Lemmon. Newsfeeds may be touting a light-up-the-sky naked-eye show for January, but it will be a modest 4th-magnitude peak favoring observers south of the equator.

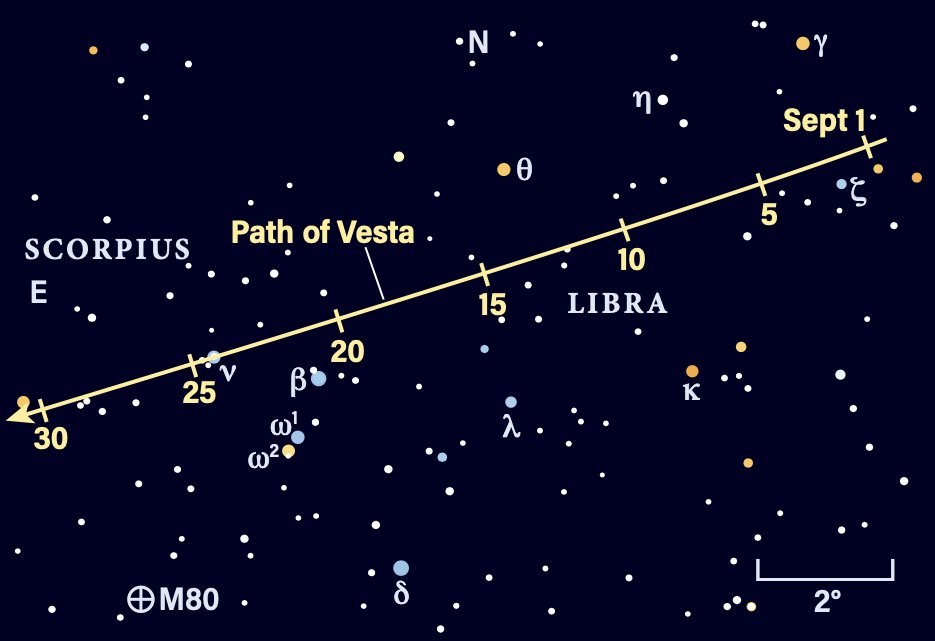

Locating Asteroids: Past its peak but holding the torch

It’s time to use a small scope to locate 4 Vesta. Slowly fading through magnitude 7.8, it also lies low in the southwestern sky, where its light will be attenuated by the longer path through our atmosphere. Don’t wait for full darkness. Fortunately, it’s a simple hop from ruby Antares up to the showcase double star Beta (β) Scorpii and a slide westward toward the lozenge-shaped quad of Zeta (ζ) Librae stars.

On the 12th, Vesta creates an optical double star with a slightly brighter companion only a couple of arcminutes away. Is the asteroid’s light somewhat “flatter” than the star’s? Egg-shaped Vesta is 330 miles across, appearing to us 0.3″ wide — size of a star’s Airy disk in a 12-inch scope.

The highlight of the month takes place on the 24th, when Vesta becomes the 5th component of Nu (ν) Scorpii. In 1905, Agnes Clerke called this star “perhaps the most beautiful quadruple system in the heavens.”

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. September 1

9 p.m. September 15

8 p.m. September 30

Planets are shown at midmonth