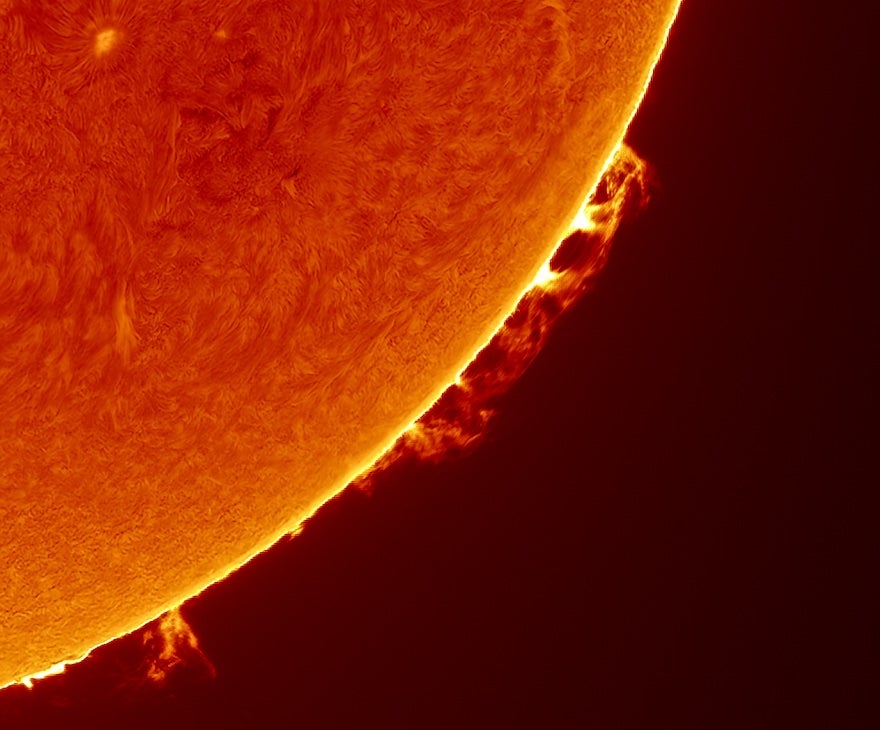

The Sun’s magnetic field constantly blasts particles from its surface into space. On Earth, we experience this steady stream of charged particles as the regular solar wind, which fuels aurorae. But our planet also must deal with the occasional fallout from strong outbursts during particularly powerful solar storms. However, for all of the downstream effects Earth experiences thanks to the Sun’s magnetic field, the true nature of this enigmatic field remains one of Sun’s most elusive mysteries.

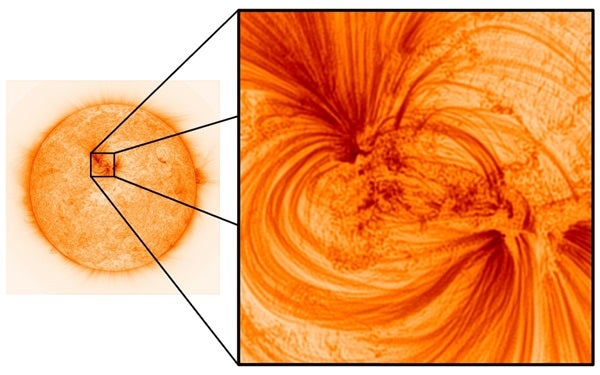

Now, new images are bringing scientists one step closer to understanding this important phenomenon by revealing, for the first time, the extremely fine details of our star’s magnetic field — details too intricate to have previously been seen.

Viewing the Sun’s delicate features

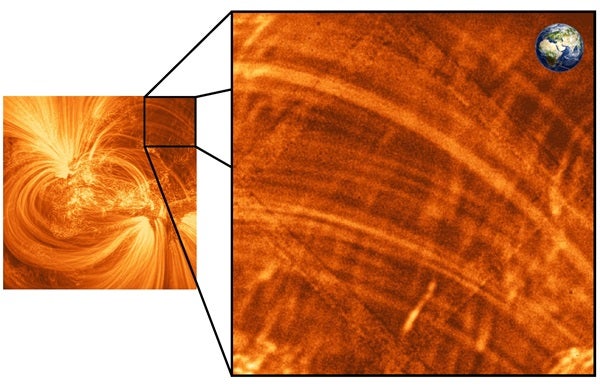

The new close-up images were taken by NASA’s High Resolution Coronal Imager, or Hi-C. They show never-before-seen bundles of delicate magnetic field lines threading across the Sun’s atmosphere. These lines, which trace the magnetic field itself, are visible thanks to the particles of million-degree plasma trapped within. Each field line is only about 310 miles (500 kilometers) across, about the driving distance between Chicago and Cleveland.

What we can learn from the life cycles of stars? Astronomy’s free downloadable eBook, Stars: The galaxy’s building blocks contains everything you need to know about how stars live, die, and change their galactic homes over time.

By capturing views of these previously invisible filaments, the researchers are now forced to reconsider what other features could be hiding in the regions of the Sun’s atmosphere that appear dark or bland. Thanks to Hi-C’s impressive resolution, astronomers have turned an unknown unknown into a known unknown.

Hi-C is not aboard a spacecraft; instead, it’s briefly carried aloft by a suborbital-flight rocket. Once in the air, the telescope is capable of zooming in on solar features just 43 miles (70 km) across, or just 0.01 percent the width of the entire Sun. That makes these photos of the Sun’s atmosphere the highest-resolution versions ever taken.

Switching to high-def

“Until now, solar astronomers have effectively been viewing our closest star in ‘standard definition,’ whereas the exceptional quality of the data provided by the Hi-C telescope allows us to survey a patch of the Sun in ‘ultra-high definition’ for the first time,” Robert Walsh, institution lead for the Hi-C team and an astrophysicist at the University of Central Lancashire in the U.K, said in a press release.

“Think of it like this: If you are watching a football match on television in standard definition, the football pitch looks green and uniform. Watch the same game in ultra-HD and the individual blades of grass can jump out at you — and that’s what we’re able to see with the Hi-C images. We are catching sight of the constituent parts that make up the atmosphere of the star.”

Now that we’ve actually seen these delicate threads, the next step is to understand them. Researchers aren’t yet sure what generates these fine magnetic field lines. They also don’t know how they affect observed things like the solar wind and coronal mass ejections, with the latter capable of pumping out billions of tons of material into space.

Moving forward, the international Hi-C team is working to plan the telescope’s next suborbital flight, where they hope to combine their observations with data taken simultaneously by the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter.

The new research was published April 1 in The Astrophysical Journal.