Key Takeaways:

- The Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra is visible with a 4-inch or larger telescope during the Northern Hemisphere's summer and fall, located midway between Beta Lyrae and Gamma Lyrae.

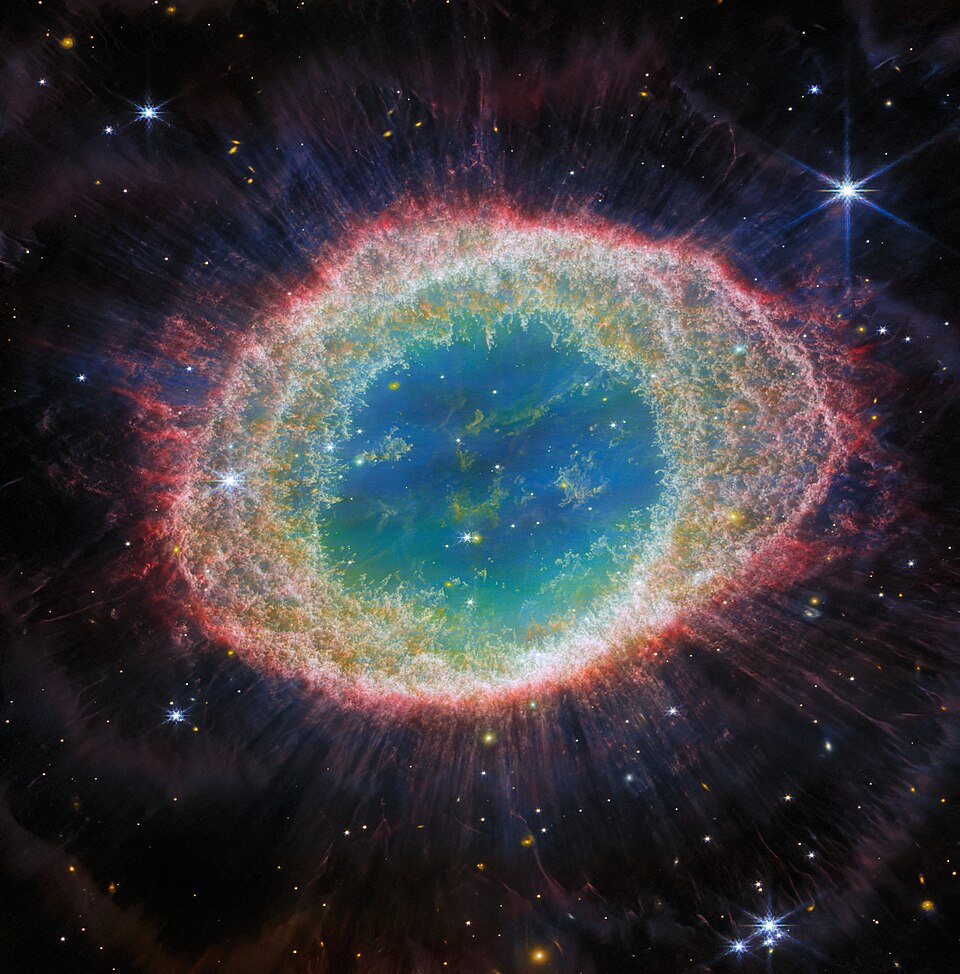

- M57, with a magnitude of 9.7 and an apparent size of 71 arcseconds, appears as a brighter, thicker ring at higher magnifications (100x or more) due to its concentrated light.

- Classified as a planetary nebula, M57 is a gas shell ejected from a Sun-like star, leaving behind a white dwarf star that is no longer generating energy.

- Observing M57's 15th-magnitude central white dwarf star presents a significant challenge, requiring a telescope of 16 inches or larger, high magnification (300x-400x), and excellent viewing conditions.

If you own a telescope with an aperture (the size of the lens or mirror) of 4 inches or more, there’s a wonderful object now high in the sky as darkness falls. It’s called the Ring Nebula, also known as M57 — the 57th object on French comet hunter Charles Messier’s famous list. He discovered the Ring in 1779.

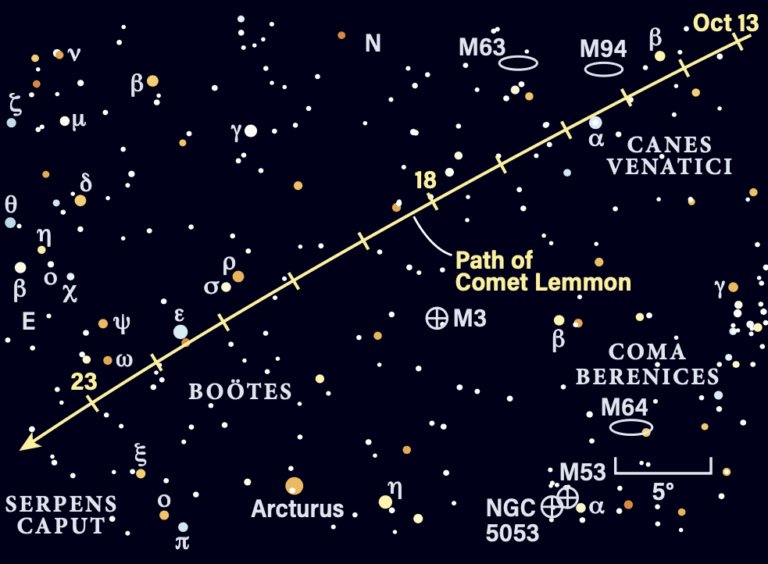

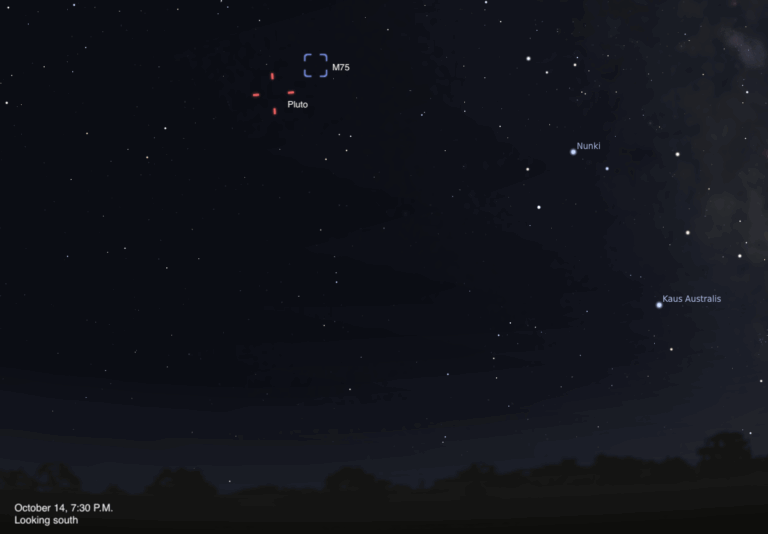

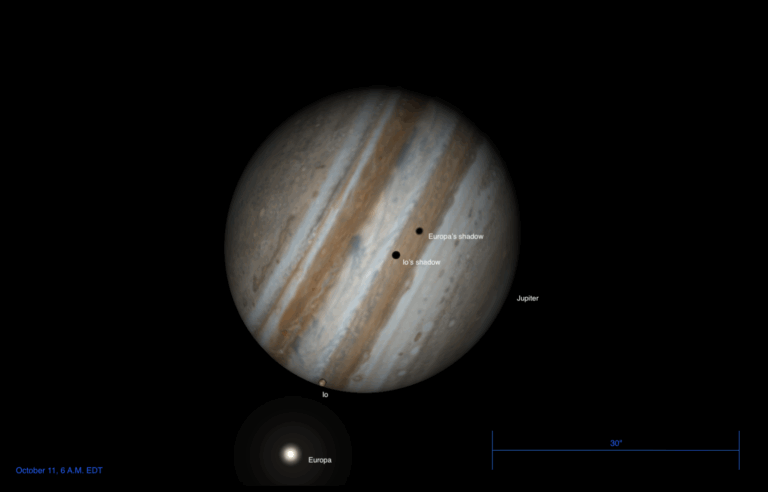

The Ring Nebula lies in the direction of the constellation Lyra the Harp, which we see best during the Northern Hemisphere’s summer and fall. The main part of Lyra is one brilliant star — Vega — and a crooked box of four fainter stars nearby. On a star chart (and then in the sky), locate Beta Lyrae and Gamma Lyrae. These two stars make the end of the box that lies farthest from Vega. Roughly midway between them, you’ll find the Ring Nebula.

The Ring glows at magnitude 9.7, which is relatively bright for such objects. Its small size, only 71″ across, concentrates that light, making it easier to see. By the way, you can spot the Ring Nebula through a telescope smaller than 4 inches. With that size of an instrument, however, it will appear as a pale gray ball. Through larger scopes, and at a magnification of 100x or more, you’ll notice the outer part of the ball looks thicker than the central region. This gives M57 its distinctive ‘‘ring’’ appearance.

Scientists classify M57 as a planetary nebula. In the 19th century, observers using small scopes with optics not as good as those we currently use likened the appearance of these objects to planets. In reality, a planetary nebula is a shell of gas ejected from a Sun-like star that has gone through its life and used up its nuclear fuel. What remains where the star used to be is a white dwarf, a still-hot object, but one that isn’t generating energy like the Sun does. It’s simply a celestial cinder that will cool for billions of years.

Spotting M57’s central white dwarf star ranks as a difficult observing challenge that will test you, your telescope, and the quality of your observing site. Through a 16-inch or larger telescope on a night of excellent seeing, use an eyepiece that yields between 300x and 400x. Keep in mind you’re searching for a 15th-magnitude star against a background that’s not completely dark. if the central star doesn’t show itself immediately, gently tap on the telescope’s tube. At such high magnification, tapping with one finger should do. Because the human eye is sensitive to motion, you may see the white dwarf at this point. German astronomer Friedrich von Hahn discovered the star in 1800.