Key Takeaways:

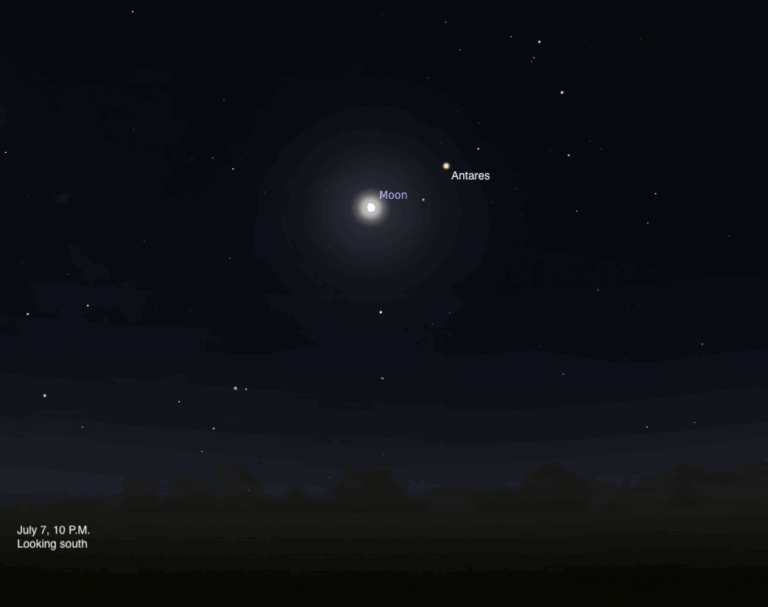

Now is the time when Moon-watchers try for a glimpse of a young Moon — one that is roughly 1 day past new phase. Your best dates to see a day-old crescent are February 28 and March 30. You’ll need an observing location that affords a low, open western horizon. Skies must be clear — low-lying haze will conceal the Moon.

Begin your search 10 to 15 minutes after sunset. The Moon will be no more than 10° above the horizon (remember, the Full Moon appears ½° wide), so concentrate on the area above and slightly left of the point on the horizon where the Sun set. If your unaided eyes fail to capture the Moon, try using binoculars. A young Moon will appear as a glimmering hairline curve, barely visible in the evening twilight.

The waxing crescent Moon most casual observers notice appears between 2 and 4 evenings after New Moon. We’ll have two opportunities this month to enjoy an early evening audience with this “Cheshire cat” Moon — the 1st through the 3rd, and again from March 31 through April 2.

What causes earthshine? Leonardo da Vinci explained it 5 centuries ago. A master at understanding the interplay of light and shadow, he reasoned that sunlight reflected from Earth illuminates the lunar surface. He understood that, viewed from a crescent Moon, Earth would appear as a dazzling, nearly full orb. The nighttime lunar landscape would be bathed in brilliant earthlight — the light we see as earthshine.

Because earthshine is a reflection of Earth’s atmospheric conditions, its intensity varies. Clouds reflect more sunlight than land or sea, so a cloudy Earth produces a more prominent earthshine than a fair-weather Earth. Earthshine diminishes as the Moon’s crescent widens and brightens.

March is Messier marathon month. I’ll be “duking it out” with Phil Harrington again. For the past 2 years, clouds have scuttled the event here in the Northeast. Last year, I tried a make-up marathon in April. Final tally: 98 “kills.” I’ll have to do much better this year if I want to beat the Binocular Man — especially now that I’ve learned the secret to his Messier marathon success.

Around sunset on a Messier marathon evening, Phil drives out to his dark-sky site on Long Island. On the side of a barn, he tacks up a poster depicting all of the Messier objects. Once evening darkness sets in, he illuminates the poster with a lantern, then trudges to a spot 100 yards away. He scans the chart with his binoculars, dutifully checks off everything on his Messier list, then packs up and heads home for a good night’s sleep. When Phil says he was “clouded out,” he really means the batteries to his lantern failed!

Next month: Will the Cheshire cat devour the Pleiades? Plus, it’s party time — astronomically speaking.