Key Takeaways:

The universe is full of extreme phenomena. Perhaps this is what draws some people to astronomy — it has some of the most extreme physics out there. And supernovae are some of the most extraordinary objects that also have the benefit of being visible to astronomers here on Earth, even long after the explosive event itself.

An incredible amount of energy is involved in a supernova explosion. When I was preparing a talk on how all the elements are made for the 2018 Texas Star Party, I came across a figure for how much energy is output from a single supernova: 1044 Joules (J). A 1 followed by 44 zeroes is an enormous number — 100 million trillion trillion trillion. I wanted to translate that to a somewhat more comprehensible number: How many nuclear bombs is that? The bomb dropped on Hiroshima during World War II was 15 kilotons (kt); 1 kt is about a trillion joules (1012 J) of energy, so one Hiroshima detonation is about 1013 J. This means that one supernova is equivalent to 1031, or 10 million trillion trillion Hiroshima detonations.

This figure blew me away. Even more incredible is that this represents the kinetic energy of the ejected particles alone — neutrinos carry away another 1046 J. As bright as they are, sometimes outshining their host galaxies, the light output from a supernova is only a small fraction of its total energy release.

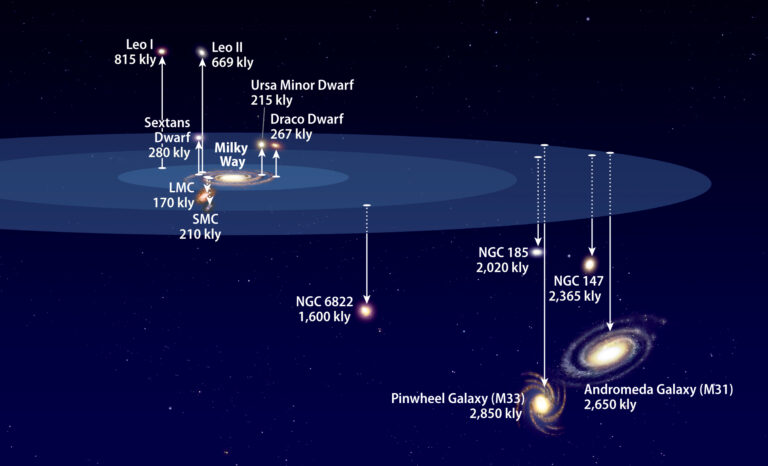

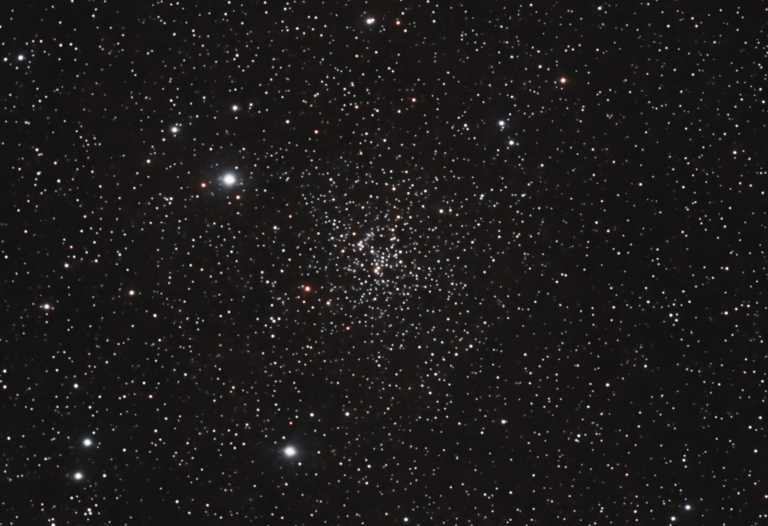

Supernovae are bright enough that even those in other galaxies are often visible through amateur telescopes — sometimes visually, such as SN2023ixf in M101 in May 2023. I had the pleasure of seeing that one with my own eye through a 16-inch Dobsonian. With a camera, backyard observers can often spy supernovae in galaxies tens of millions of light-years away. In fact, many supernovae are discovered by amateurs.

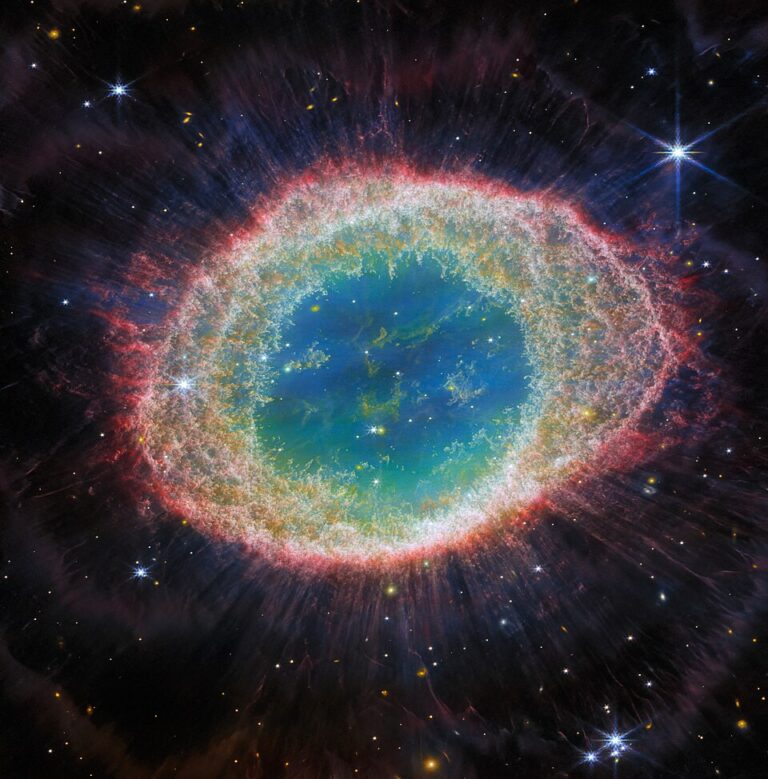

Even when there’s not a new stellar explosion in the sky, there are several ancient supernova remnants to explore. Most easily visible in amateur scopes is the Crab Nebula, or M1, located in Taurus. The supernova was recorded by several societies in 1054 c.e. when it was visible during the day for three weeks, and only faded from nighttime skies two years later. The stellar core left behind is now a rapidly spinning neutron star known as a pulsar. It emits enough energy to light up the still-expanding cloud of stellar ejecta that surrounds it, making it visible as a fuzzy splotch at the eyepiece and in spectacular detail with a camera.

Another supernova remnant accessible to visual astronomers is the sprawling Veil Nebula (NGC 6960, among others) in Cygnus, also known as the Cygnus Loop. The star that created it 10,000–20,000 years ago was 20 times the mass of the Sun, and the supernova would have been visible during the day, outshining Venus. The still-glowing arcs of stellar material are best seen with a nebula filter under a dark sky — the Eastern Veil, Western Veil, and central Pickering’s Triangle regions are breathtaking in my 16-inch Dobsonian with an Oxygen-III filter. Like the Crab, the Veil is also still expanding, at a rate of some 932,000 mph (1.5 million km/hr).

Supernovae have captured the imagination and delighted stargazers all over the world. Both recent and ancient supernovae are worth exploring with a telescope. Perhaps you’ll discover the next one!