Key Takeaways:

- Mars, though past opposition, remains visible in the evening sky, exhibiting a magnitude of 1.6 and appearing near Spica, but its small apparent size limits telescopic detail.

- Saturn, approaching opposition in September, offers a favorable telescopic view in August with a 19" disk and 43" rings, and is significantly brighter than surrounding stars at magnitude 0.7.

- Venus and Jupiter, visible in the early morning, present a close conjunction around August 12th, with Venus significantly brighter than Jupiter, though telescopic views may be hampered by atmospheric conditions.

- Mercury reaches greatest elongation on August 19th, becoming visible before dawn, and a lunar occultation of Antares is visible from specific locations in South America and New Zealand.

Although Mars reached opposition in January, it remains a fixture on August evenings. In fact, it’s the only planet visible as twilight fades to darkness. The planet moves eastward against the background stars of Virgo, approaching that constellation’s luminary, 1st-magnitude Spica. The magnitude 1.6 Red Planet makes a nice color contrast with the blue-white star.

Unfortunately, Mars lies on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth and thus appears small through a telescope. Its 4″-diameter disk won’t show any detail.

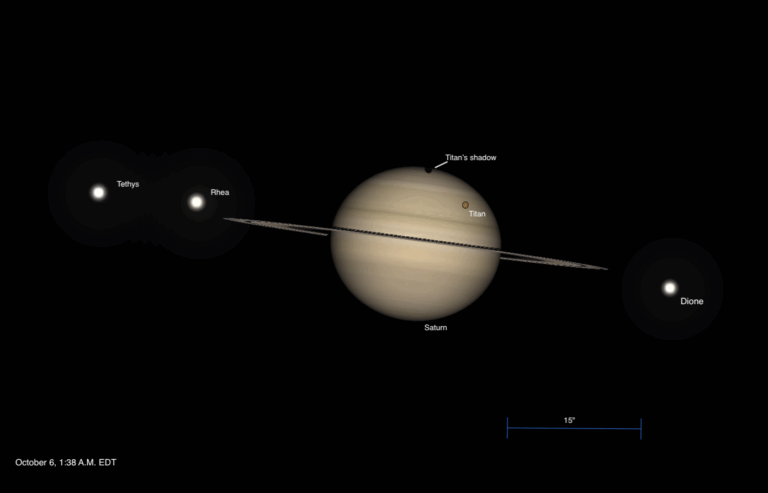

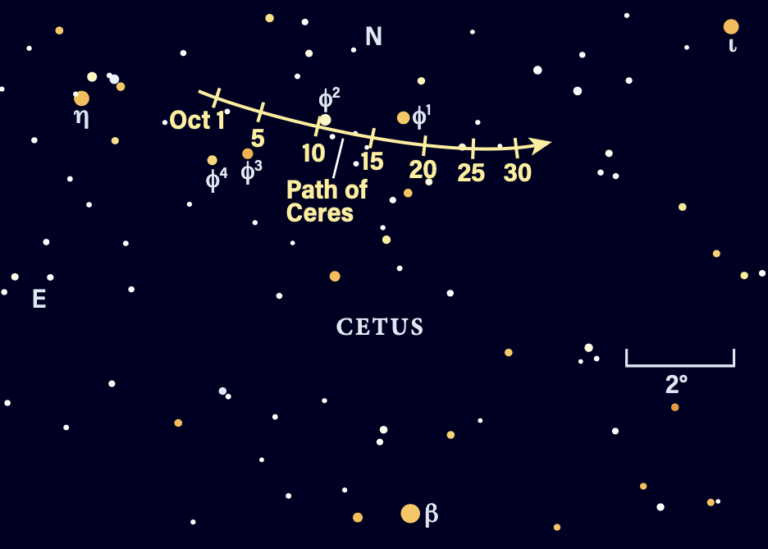

Later in the evening, Saturn pokes above the eastern horizon. You can find it in southern Pisces, near that constellation’s borders with Aquarius and Cetus. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.7, significantly brighter than any nearby star.

This gas giant world will reach opposition in September, but the view through a telescope this month is nearly as good. In mid-August, the planet’s disk measures 19″ across while the rings span 43″ and tilt 3° to our line of sight.

No other naked-eye planet appears until the wee hours. Soon after Orion the Hunter’s impressive figure clears the eastern horizon, the solar system’s two brightest planets come into view.

Venus rises first in early August, a bit more than two hours before the Sun. It starts the month in far western Gemini, quickly traverses the Twins, and then enters Cancer in August’s final week. On the 31st, Venus lies 2° southwest of the Beehive star cluster (M44).

The dazzling inner planet fades imperceptibly this month, from magnitude –4.0 to –3.9. Yet this brilliance doesn’t portend a great telescopic appearance. Venus’ diameter shrinks from 14″ to 12″ during August while its phase waxes from 75 percent to 84 percent lit.

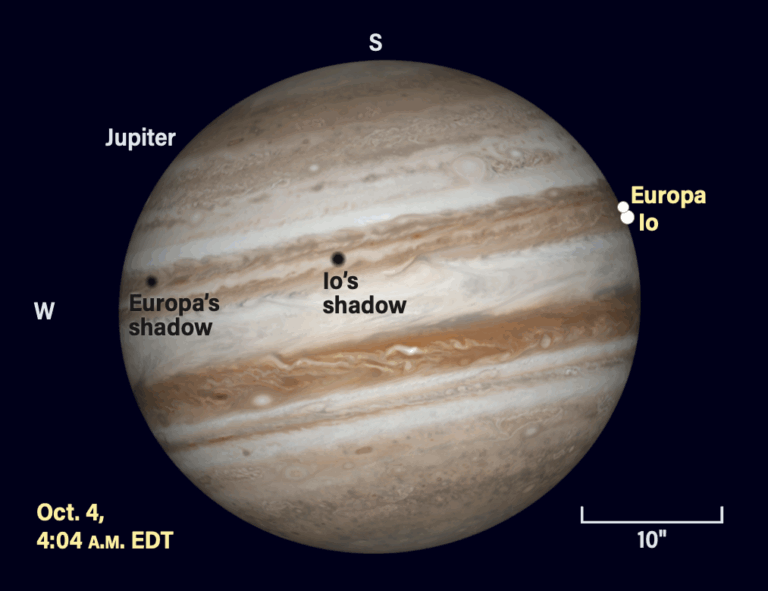

On Aug. 1, Jupiter rises nearly an hour after Venus. The outer planet climbs higher with each passing day, however, and soon catches up to its sibling. The two meet on the 12th, with Venus sliding 0.9° south of Jupiter. For a couple of mornings, they will look like a pair of bright headlights in the twilight. Venus appears seven times brighter than magnitude –1.9 Jupiter.

Because the giant planet lies low in the morning sky, where the seeing tends to be poor, don’t expect sharp views through your telescope. Still, you should see its 33″-diameter disk and its four largest moons.

Mercury emerges briefly before dawn in mid-August. The innermost planet passes between the Sun and Earth at inferior conjunction on the 1st and then climbs rapidly into view. Mercury reaches greatest elongation Aug. 19, when it lies 19° west of the Sun and stands 6° high in the east-northeast a half hour before sunrise. To find the planet, draw a line from Jupiter to Venus and extend it a bit more than twice that distance. Mercury shines at magnitude 0.0.

A waxing gibbous Moon occults the 1st-magnitude star Antares twice this month. The Aug. 4 event favors observers at the southern tip of South America. From Punta Arenas, Chile, the star disappears at 2h31m UT and reappears at 3h33m UT. Viewers in parts of New Zealand’s South Island can witness the Aug. 31 occultation. From Christchurch, Antares disappears at 11h49m UT and reappears at 12h05m UT.

The starry sky

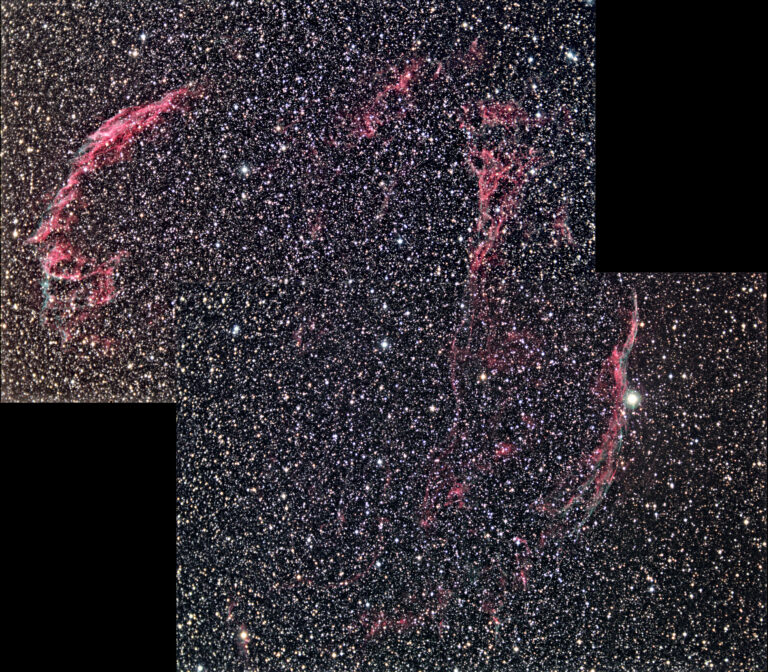

August certainly offers some of the finest evening views of the starry sky. Nothing quite compares with being under the spectacular Milky Way on a moonless night away from the lights of any towns or cities. This year, the Moon abandons the evening sky from around Aug. 12 to 24.

People sometimes ask me where the best place is to see the Milky Way. The easiest answer is any place without light pollution. But if you want a more technical answer, I would say the best latitude from which to view the Milky Way is around 29° south. That’s where the center of the Milky Way passes directly overhead when the sidereal time is about 17h45m (early evening in mid-August). This latitude corresponds to southern Australia, southern Brazil and northern Argentina and Chile in South America, and South Africa.

That said, the brightest part of the Milky Way lies a few degrees east of the galactic center, in the so-called Large Sagittarius Star Cloud. It’s easy to mistake this huge starry assemblage for our galaxy’s entire central bulge. It is not, however — it represents only about one third of the bulge. The rest remains hidden behind thick clouds of galactic dust. As you gaze at the Milky Way, remember that its equator actually runs through the dark region adjacent to the Large Sagittarius Star Cloud.

Within this cloud lies the globular star cluster NGC 6522. English astronomer William Herschel discovered the cluster in 1784, three years after he first spotted the planet Uranus. The 8th-magnitude globular resides just 37′ northwest of the magnitude 3.6 star Gamma2 (γ2) Sagittarii, making it easy to spot through a telescope or binoculars with an aperture of at least 50mm.

The region centered on NGC 6522 exhibits far less absorption of light than nearby areas. German astronomer Walter Baade studied this area with the 100-inch Hooker Telescope on California’s Mount Wilson during the 1940s, which allowed him to estimate the distance to the center of our galaxy. Astronomers now refer to this relatively transparent part of the sky as Baade’s Window.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 30° south latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

9 p.m. August 1

8 p.m. August 15

7 p.m. August 31

Planets are shown at midmonth