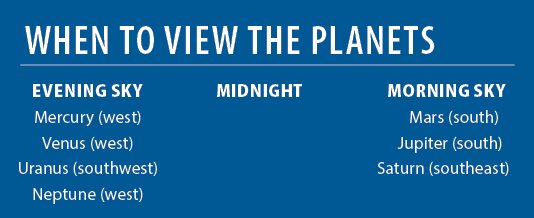

But the month’s best planet action occurs before dawn. Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn congregate in the morning sky, where they provide exceptional views for casual and serious observers alike.

Our tour of the night sky begins low in the west after sunset in late February. On the 28th, Venus lies only 12° east of the Sun and stands 5° above the horizon a half-hour after sundown. The planet shines brilliantly, however, at magnitude –3.9, and shows up despite the bright twilight.

If you target Venus with binoculars, you also might spot Mercury. The innermost planet passes on the far side of the Sun on February 17 and reappears at dusk soon thereafter. By the 28th, it lies 2.3° to Venus’ lower right. Because Mercury shines more dimly, at magnitude –1.4, and has a lower altitude than its neighbor, glimpsing it requires an unobstructed horizon and a clear, haze-free sky.

Distant Neptune lies near Venus in late February, passing within 1° of the brilliant planet the evenings of February 20 and 21. But the eighth planet glows at 8th magnitude and will be invisible in twilight.

Fortunately, Neptune is far better positioned in early February. On the 1st, the planet stands 10° high in the west-southwest as the last glints of twilight fade away. You can find it through binoculars against the backdrop of Aquarius. First, locate 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii. Neptune lies 1.1° due east (upper left) of this star. The pair dips lower with each passing day and disappears in twilight during February’s second week.

Uranus stands halfway to the zenith in the southwest as twilight closes in early February. The 6th-magnitude planet resides among the background stars of eastern Pisces. On the 1st, it lies 3° from both 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Piscium and 5th-magnitude Mu (μ) Psc. Uranus’ eastward motion carries it to a point 2.3° west of Omicron on the 28th.

Uranus sets shortly after 11 p.m. local time in early February and close to two hours before that at month’s end. You’ll get your best views through a telescope in early evening when the planet still lies reasonably high. The ice giant’s 3.5″-diameter disk glows with a distinctive blue-green hue.

Although the midnight sky is devoid of planets for most of February, the wait for the next batch of solar system worlds is well worth it.

A trio of spectacular planets stretches out across the southeastern sky before dawn all month. Jupiter, Mars, and Saturn line up along the ecliptic — the Sun’s apparent path across our sky that the planets follow closely. They form a beautiful wintery scene once Saturn, the last to rise, clears the horizon by 5 a.m. local time. But the most stunning vistas come when the trio becomes a quartet as a waning Moon slides past from February 7 to 11.

Jupiter is the first to rise. It pokes above the horizon shortly before 2 a.m. local time in early February and nearly two hours earlier by month’s close. It lies in Libra, a constellation that climbs 30° high by 5 a.m. The brilliant orb dominates the predawn sky throughout February, brightening from magnitude –2.0 to –2.2 during the month. The Last Quarter Moon passes 4° to Jupiter’s upper right on the 7th.

Patient viewers are rewarded with remarkable views of delicate wisps and swirls in Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere. The gas giant’s cloud tops resolve into a series of alternating belts and zones adorned with dark spots and feathery festoons.

Jupiter’s four bright moons provide a constantly changing tableau visible through any telescope. Innermost Io moves fastest, completing an orbit every 1.8 days, while Europa takes 3.6 days, Ganymede 7.2 days, and Callisto 16.7 days. Sometimes a satellite may disappear behind the giant planet or get eclipsed by its shadow. On the opposite side of its orbit, a moon can cast a distinct shadow onto the planet’s cloud tops or hide in plain sight as it passes in front of the gaseous world.

In its quick orbit, Io experiences more of these events. A good example occurs February 3. At 4:00 a.m. EST, the satellite’s shadow falls near the center of Jupiter’s disk while Io itself lies just off the planet’s eastern limb. The scene dramatically reveals the geometry of the Sun’s illumination relative to our viewpoint. The other three moons stretch out west of Jupiter in reverse order of their orbital distances.

East Coast observers can see Ganymede eerily fade away west of Jupiter on February 6 starting at 2:43 a.m. EST. As the moon enters the planet’s shadow, it takes about 15 minutes to disappear completely. If you return to Jupiter at 4:24 a.m. EST, you can see it gradually return to view as it exits the shadow.

Because the orbital plane of the satellites tilts slightly to our line of sight, outermost Callisto does not pass in front of or behind the planet’s disk. You can spot this moon due south of Jupiter just before dawn February 11. That morning brings two other intriguing events: Europa disappears into Jupiter’s shadow starting at 5:08 a.m. EST, and Io reappears from behind the planet 10 minutes later.

Mars lies 12° east of Jupiter on February 1 and rises an hour after the giant planet. You’ll find the Red Planet against the backdrop of Scorpius, 0.4° south of 2nd-magnitude Beta (β) Scorpii and 8° northwest of its stellar look-alike, Antares. Mars’ eastward motion carries it into Ophiuchus on the 8th, when a fat crescent Moon lies between it and Jupiter. The following morning, a slimmer crescent Moon appears 5° to Mars’ upper left. Astroimagers will want to be ready February 24, when the planet passes 15′ north of 9th-magnitude globular star cluster NGC 6287.

On February 10, Mars passes 5° due north of Antares. It’s a perfect morning to compare the brightnesses and colors of the two objects, and come to understand why ancient observers named the star Antares, which literally means “rival of Mars.”

The gap between Mars and Earth closes during February, and the ruddy planet brightens as a result. It shines at magnitude 1.2 on the 1st, magnitude 1.0 on the 15th, and magnitude 0.8 on the 28th.

As Mars approaches Earth, it also appears to grow larger when viewed through a telescope. It swells by nearly 20 percent in February, reaching 6.6″ across by the end of the month. Although still too small to show much detail, the planet’s diameter will be nearly four times bigger by the time it reaches opposition in late July.

The final member of our planetary trio rises just before 5 a.m. local time February 1. Saturn climbs 10° above the southeastern horizon an hour before sunup and appears obvious in the gathering dawn. It shines at magnitude 0.6, noticeably brighter than any of the background stars in its host constellation, Sagittarius. It’s only real competition comes when a slender crescent Moon appears 2° above it the morning of February 11.

Viewing conditions improve noticeably by the end of February, when Saturn stands 15° high at the start of twilight. First, scan the area with binoculars and enjoy the rich backdrop of the Milky Way. Then, grab a telescope and catch your first good looks of the planet this year. Any instrument should show the planet’s 16″-diameter disk wrapped in a glorious ring system that spans 36″ and tilts 26° to our line of sight. The 8th-magnitude dot you see lurking beyond the rings is Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

Shortly after the Moon finishes its trek past the morning planets, it passes in front of the Sun. On the afternoon of February 15, people in most of Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay can view a partial solar eclipse. From the southern tip of South America, the Moon covers 35 percent of the Sun’s diameter at maximum. Greatest eclipse occurs in Antarctica, where 60 percent of the Sun will be hidden from view. As with any partial solar eclipse, use a safe solar filter to view it directly.

The waxing crescent Moon not only thrills neophyte viewers, but it also delights veteran selenophiles. Late winter and early spring are the best times to view this lunar phase because the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun across our sky that the Moon and planets follow closely — makes a steep angle to the western horizon after sunset. Thus, the waxing crescent Moon appears higher in the sky than it does at other times of year.

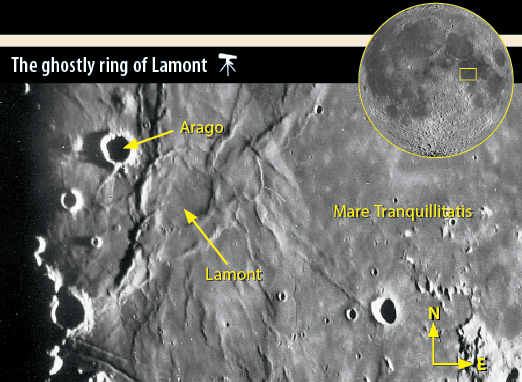

Let’s focus on Luna the evening of February 20, less than three nights before First Quarter phase. The 25-percent-lit Moon stands more than 40° high in the southwest an hour after sunset and remains on view well past 10 p.m. local time. Aim your telescope toward Earth’s satellite and focus your attention just north of the equator. On the western shore of Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), you’ll find a zone rife with sinewy ridges adorning the mare’s frozen face.

Literally buried under Tranquility’s mostly north-south ridges is a ghostly ring named Lamont. Astronomers think this was a fairly normal impact crater in the Moon’s youth. But lava welling up from beneath the surface flooded the crater to its rim a few billion years ago, leaving behind the ghostly ring. A second ring, about twice Lamont’s size and concentric with it, is trickier to see under less-than-ideal conditions.

Long after Lamont formed, a smaller impactor carved out the 16-mile-wide crater Arago to its northwest. Look just north of Arago and you’ll see a modest bump, which is the largest of a family of volcanic domes in this neighborhood. The rings and domes have such gentle slopes that they disappear under the higher Sun angle the following evening.

The annual calendar of meteor showers suffers a lull between early January’s Quadrantids and the Lyrids of late April. Observers under a dark sky typically can see a half dozen or so meteors per hour shortly before morning twilight begins.

But the tiny dust particles that cause these sporadic meteors also permeate the inner solar system. These fine grains show up as a cone-shaped glow in the west on dark February evenings. Because the dust hugs the solar system’s plane, or ecliptic, the glow aligns with the zodiacal constellations and astronomers call it the “zodiacal light.” It appears best on evenings in February and March because the ecliptic then makes a steep angle to the western horizon.

Look for this soft glow under a dark sky from February 2 to 16, when the Moon is out of the early evening sky.

The roller coaster from faint to bright comets and back continues in 2018. The first months of this year find us near the bottom of the ride. February’s best entry is Comet PANSTARRS (C/2016 R2), which should glow at 10th or 11th magnitude. You’ll need a 5- or 6-inch telescope to capture its light under a dark sky, and you’ll want to avoid the month’s first few evenings and its final 10 days when the Moon shares the stage.

The comet rides high in the south as darkness settles in. It appears against the backdrop of Taurus, near the sparkling Pleiades star cluster (M45). The star-hop to the comet won’t be easy because the background here has few obvious patterns.

You’re looking for a small, round, diffuse glow similar to a companion galaxy in the Virgo Cluster but without the bright parent to guide you. PANSTARRS may not be visible at low power. If a quick scan doesn’t reveal it, use medium power (around 100x) and search near the position shown on the finder chart.

Once you spot it, bump up the magnification to 150x or so. This darkens the field and makes the comet more noticeable. The glow you see comes mostly from sunlight reflecting off dust particles. PANSTARRS’ gas output should be weak because the comet lies nearly three times as far from the Sun as Earth does.

The robotic Pan-STARRS system picked up C/2016 R2 in September 2016, nearly three months after discovering C/2016 M1, which soon will take over R2’s spot at the top of our observing list. Thankfully, the comet roller coaster will return us to much brighter subjects this fall, when 46P/Wirtanen could reach naked-eye visibility.

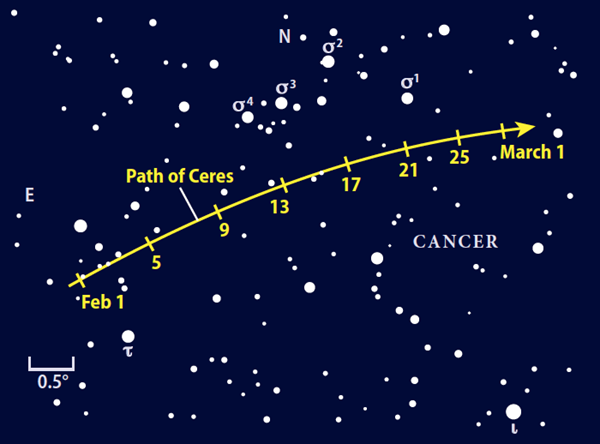

If you’re new to tracking objects in the asteroid belt, Ceres offers a perfect starting point. With just binoculars or a small telescope, you can watch this dwarf planet shift positions relative to the background stars from night to night, an unambiguous sign that it belongs to our solar system.

To find Ceres, start with the Star Dome map at the center of this magazine. Locate the bright stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini just left of center and then the constellation Cancer the Crab closer to the eastern horizon. The star at the northern end of this pattern is 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Cancri, and it’s the brightest object in the chart below. From there, head a few degrees northeast to the four 5th- and 6th-magnitude stars labeled Sigma1 (σ1) to Sigma4 (σ4) Cancri. Just south of them lies a relatively empty region through which 7th-magnitude Ceres slowly treks.

On a sheet of paper, sketch a handful of the brightest stars. Then, drop a tiny point into this framework to represent which object you suspect to be Ceres. Refer to this page when you return to the area a night or two later. You should notice right away that the dot marking Ceres has moved.

We’re fortunate to live at a time when we can connect this moving mote of light to the magnificent world being revealed by the Dawn spacecraft. A few years ago, scientists could only guess at what lies on its surface — and no one expected mountains of salt.