For millennia, the planet Jupiter appeared to our ancestors as little more than a starlike point of light. The Romans revered it enough to name it for the lord of their gods. But not until the invention of the telescope did we discover more about it: four huge moons (and many smaller ones); the roiling Great Red Spot, a storm wider than Earth; and the planet’s sheer magnificence as the largest and most massive world in the solar system.

Half a billion miles (800 million kilometers) away, Jupiter languished at the ragged edge of human knowledge, seemingly unreachable. Then, 50 years ago today, a tiny probe roared into the Florida night to unmask this monstrous world for the first time. Pioneer 10 would teach and surprise us in equal measure, and provide a pathfinder for missions to come.

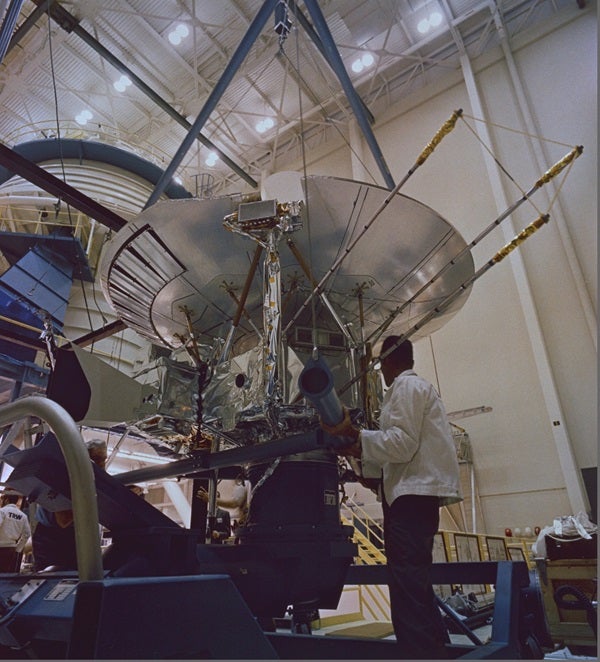

The quarter-ton, car-sized Pioneer 10 probe was designed to survey not just Jupiter but the entire solar system environment beyond Mars — including the never-before-crossed asteroid belt — for the first time. After passing Jupiter, Pioneer 10 would plunge into the outer solar system and ultimately leave the Sun’s realm forever.

An auspicious start

Twice thwarted by a power cut and high winds, its Atlas Centaur rocket finally rose from Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 36A at 8:49 P.M. EST on March 2, 1972. Pioneer 10 started knocking down records right off the bat. It became the fastest human-made object to leave our planet, barreling away from Earth at 32,000 miles (51,500 km) per hour and passing the Moon within its first half-day of flight. It was an auspicious start for a voyage that may never end.

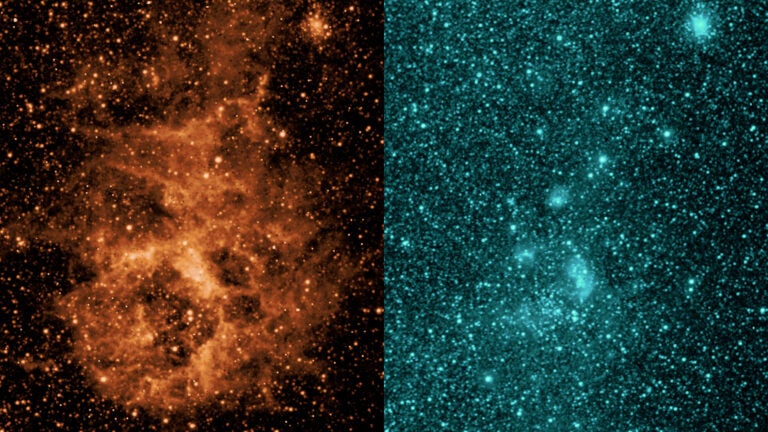

The craft was brimming with detectors for plasma and charged particles; cosmic-ray and Geiger-tube telescopes; asteroid, meteoroid and radiation sensors; infrared and ultraviolet scanners; an imaging photopolarimeter; and a magnetometer. To provide power in a realm where sunlight grew progressively weaker, Pioneer 10 carried four plutonium generators as the world’s first nuclear-powered deep-space probe.

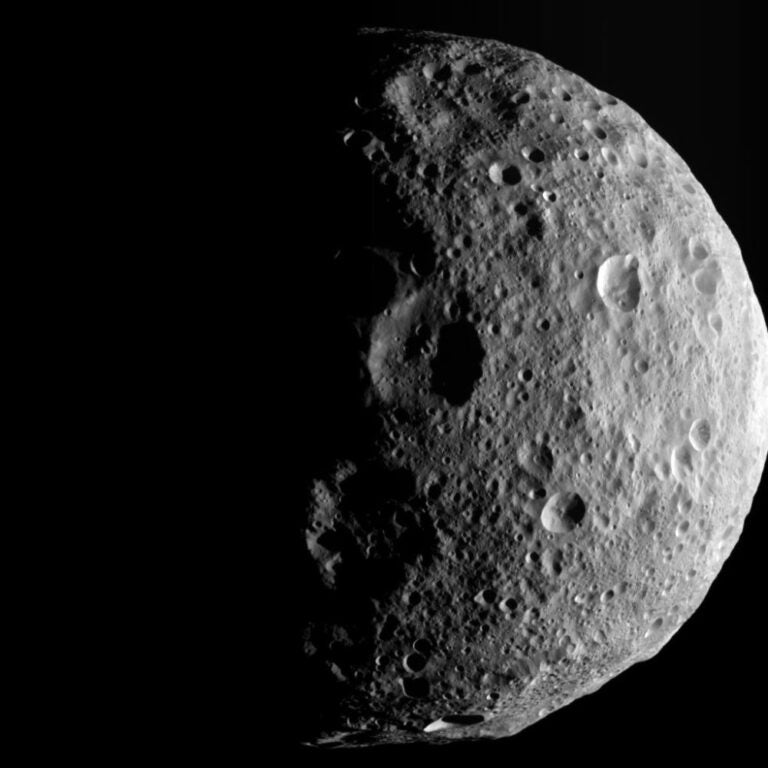

Pioneer 10’s journey into the unknown was fraught with risk. On July 15, 1972, after crossing Mars’ orbit, it entered the asteroid belt and for seven months traversed its 270-million-mile (434 million km) radial extent. Such a trip had never before been attempted. But contrary to some doomsday predictions, Pioneer 10 suffered only small-scale scarring from particle impacts along the way. “Happily,” noted the Baltimore Sun after the probe emerged from the belt in February 1973, “it has registered contact only with the sort of fine-grained debris that litters space in general.”

Encounter with the king

Pioneer 10’s encounter with Jupiter encounter commenced in November 1973. On Nov. 25, from a distance of 7 million miles (11 million km), the craft began to detect intense radiation. It found that Jupiter’s magnetosphere — a huge magnetic cavity carved by the planet into the solar wind — extended 4.3 million miles (6.9 million km) toward the Sun and likely wound backward, corkscrew-like, beyond Jupiter. Its strength was far greater than Earth’s magnetosphere and tended to ebb and flow in rhythmic harmony with the planet’s nearly 10-hour rotation.

As the spacecraft drew closer, the Great Red Spot popped into view: a churning anticyclonic storm far wider than Earth. Pioneer 10 data published in April 1974 hinted that the centuries-old spot was likely a towering mass of clouds, arising from thermal sources deep within the jovian interior.

After traveling for 641 days, at 9:25 P.M. EST on Dec. 3, 1973, the probe swept just 82,178 miles (132,253 km) above Jupiter’s cloud tops to reveal a colorful, stormy world of striking latitudinal belts and zones of vivid reds, creams, and browns. Forty-six minutes later, its first data reached the eyes and ears of the Pioneer 10 team at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. “So deluged were Pioneer scientists with transmissions of the spacecraft’s instruments,” opined the Washington Post, “they were literally changing their minds about Jupiter’s physics and chemistry every hour.”

The excited fervor was palpable. “Some of us have been looking through telescopes at Jupiter since our early teens,” NASA Administrator James Fletcher said. “This is more than we ever dreamed of.” U.S. President Richard Nixon wired congratulations, noting that humanity’s ability to explore the heavens now sat “on the threshold of the infinite.”

But Pioneer 10’s margin of survival was closer to the knife-edge than it seemed. It absorbed a thousand times the lethal dose of radiation for a human, suffering darkened optics and fried transistor circuits. Other unwanted side effects included the generation of false commands, which caused the craft to lose at least one image of the moon Io and several shots of Jupiter.

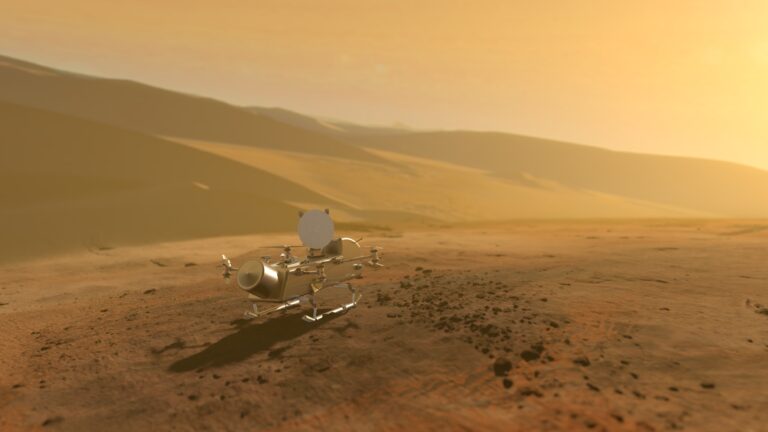

Fortunately, any changes to Pioneer 10’s systems induced by radiation disappeared in the following months, as it continued on its way. But they served as an acute reminder that future missions would need some serious beefing up to protect their equipment.

A lasting legacy

Pioneer 10’s whistle-stop tour of Jupiter officially ended Jan. 2, 1974. The brief visit nonetheless revealed much about the planet. We learned that Jupiter’s magnetic field is inclined 15° to its axis of rotation. Pioneer 10’s measurements allowed researchers to pinpoint the presence of helium in the atmosphere and confirmed long-held suspicions that this was a predominantly gaseous world with no discernible solid surface. And its data showed atmospheric temperatures were broadly the same during day and night.

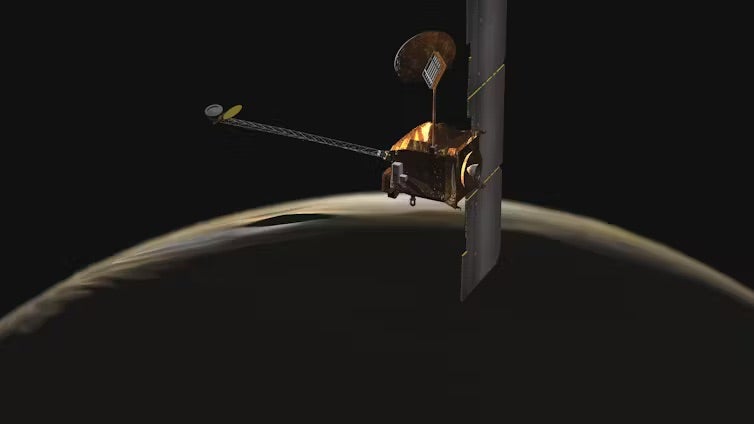

The probe’s passage through the Jovian system included a pass behind the Galilean moon Io, which astronomers suspected might possess an ionosphere of its own and, by extension, a substantial atmosphere. Pioneer 10’s data confirmed the ionosphere’s existence and even hinted that sulfur might be a key chemical component within it. But it would be several more years before the Voyagers fully revealed Io to be a world of ubiquitous, sulfur-driven volcanism.

Pioneer 10’s encounter with Jupiter was a great success. While its slow-scan images were deemed “passable” by some observers, they certainly whetted appetites for future endeavors. The probe crossed the orbits of Saturn in 1976, Uranus in 1979, and Neptune — then the solar system’s most distant planet while Pluto swung interior to the ice giant’s orbit — in 1983. NASA received the spacecraft’s last feeble radio signal in January 2003 from a distance of 7.4 billion miles (11.9 billion km). Efforts to contact Pioneer 10 two weeks later were met with silence.

Five decades after its launch, Pioneer 10 continues silently at a velocity that could zip between New York and London in eight minutes. Each year, it crosses 230 million miles (370 million km), more than twice the gulf separating Earth from the Sun, heading generally in the direction of the red giant Aldebaran, the brightest star in the constellation Taurus. It may take a couple million years to get there.

For now, the probe flies inexorably onward. The Sun remains visible in its rear view, a bright star with a magnitude of –16.3. It serves as a reassuring companion and sole reminder of a long-ago home that Pioneer 10 will never see again.