Key Takeaways:

The Perseid meteors are one of the year’s best shows for skywatchers. This year, the shower peaks on Thursday, August 12, offering great early-morning observing with no moonlight to interfere.

The Perseid meteor shower officially runs from July 17 through August 24. It’s possible to catch shower meteors at any point during that time frame — so don’t worry if your weather is poor this week — but the best time is around the shower’s peak on Thursday. If you aren’t able to catch the show Thursday morning, Friday’s prospects (August 13) are just as good. Both mornings, the shower’s radiant (the point from which shower meteors appear to originate) is high in the sky and there’s no moonlight to interfere.

Where and when to look

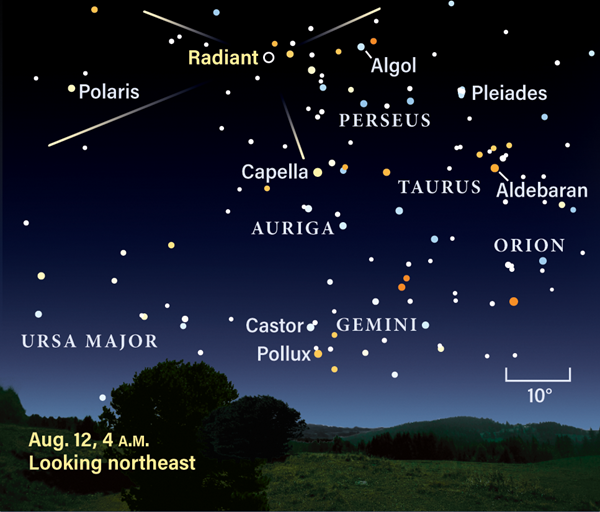

The Perseids are so named for their radiant in the constellation Perseus the Hero, who sits surrounded by several other star figures, among them Cassiopeia, Andromeda, Aries, Taurus, and Auriga. On early August mornings, you’ll find Perseus towering above Auriga the Charioteer and, closer to the horizon, Gemini the Twins.

The Perseids’ radiant sits roughly two-thirds of the way on a line drawn from Polaris — the North Star, located at the end of the Little Dipper — to Algol, the second-brightest star in Perseus. Closer to the radiant are 4th-magnitude Miram (Gamma [γ] Persei), which sits 2.5° southwest of the radiant, and 5th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Persei, just 0.7° south of the radiant. In the hour before dawn on the 12th and 13th, the radiant will be 60° high in the northeastern sky.

What to expect

The strength of a meteor shower is given by the zenithal hourly rate, or ZHR, at the shower’s peak. ZHR is a measure of the number of meteors an observer can expect to see when the radiant is at the zenith, or 90° high in the sky. This year, the Perseids’ expected ZHR at peak is 110 meteors per hour. Because the radiant won’t reach the zenith, however, most North American observers can expect to see a lower rate of about 60–90 meteors per hour, or roughly one meteor per minute, before dawn. Note, though, that a rate of 60 meteors per hour doesn’t mean you’ll see exactly one meteor each minute. Meteors are sporadic and unpredictable; you might see several over the course of just a few minutes, then none at all for the next short while.

If you prefer to watch at night, wait until moonset (around 10:30 P.M. local time on the 12th and 11 P.M. local time on the 13th) for the darkest skies. Note that at this time, Perseus has only recently climbed above the horizon and the shower’s radiant is only 20° high, cutting the number of meteors you’ll see each hour to 20 or so. The longer you stay out overnight, the higher the constellation will rise and the more meteors you’ll catch.

What’s happening

Perseid meteors are generated by debris left by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which swings close to the Sun every 133 years. Its last closest approach to our star was in 1992 and its next will be in about 100 years, in 2125. The comet was discovered in 1862 and linked shortly after to the Perseids in 1865. The shower itself has been popularly known since the 1830s, but likely appeared annually long before that date as well.

Because comets have well-defined orbits around the Sun, the debris they shed tends to stay on that orbit. When Earth’s orbit intersects the path, we see a meteor shower. As dust from Swift-Tuttle hits Earth’s atmosphere at speeds up to 133,000 mph (214,000 km/h), it burns up in a brilliant flare of light — a Perseid meteor. Most meteors burn up high in the atmosphere, more than 50 miles (80 kilometers) in altitude. None of the particles that generate meteor showers are large enough to survive their trip, so meteor showers do not produce meteorites, which are space rocks that make it through the atmosphere to hit the ground.

Top viewing tips

Watching the Perseids is easy — all you’ll need is a relatively dark sky and there’s no equipment required. It’s best to observe meteor showers with only your eyes, because meteors can appear over such a large swath of sky. Magnifying your view with binoculars or a telescope will dramatically reduce the amount of sky you’re looking at and make you miss out on much of the show.

Locate the radiant, then turn your gaze to a spot roughly the same height above the horizon but 40° to 60° away from the radiant’s position. This is the “sweet spot” where the brightest meteors with the longest trails are likely to appear. Meteors closer to the radiant will appear to have shorter trails, thanks to the perspective from which you’re seeing them.

You can opt to watch the show for as short or as long a time as you’d like — that’s one of the perks of meteor shower observing. If you’ll be outside for a while, make sure to consider your environment and, as needed, prepare with insect repellant, a blanket, hot or cold drinks, and snacks. You might also want to bring a reclining chair so you can simply relax and let your eyes scan the sky from a comfortable position.

Photographing meteors is relatively easy as well. You’ll likely want to set your camera up on a tripod with a remote for your shutter if possible. Aim your camera at the sweet spot and opt for a large aperture and long exposure time, which let you take in a good chunk of sky and can catch several trails in one shot. Be on the lookout for particularly good landmarks such as trees, mountains, lakes, or buildings you may also want to capture in addition to the sky.

Whether you’re a veteran skywatcher or a casual observer, this is one show that won’t disappoint. And while you’re out waiting to catch some shooting stars, there’s plenty of other observing targets in the sky as well — read through our weekly observing column to explore some of the other highlights in our sky this week.

Enjoy the show!