For space law to be effective, it needs to do three things. First, regulation must prevent as many dangerous situations from occurring as possible. Second, there needs to be a way to monitor and enforce compliance. And finally, laws need to lay out a framework for responsibility and liability if things do go wrong. So, how do current laws and treaties around space stack up? They do OK, but interestingly, looking at environmental law here on Earth may give some ideas on how to improve the current legal regime with respect to space debris.

What if a rocket landed on your house?

Imagine that, instead of landing in the ocean, the recent Chinese rocket crashed into your house while you were at work. What would current law allow you to do?

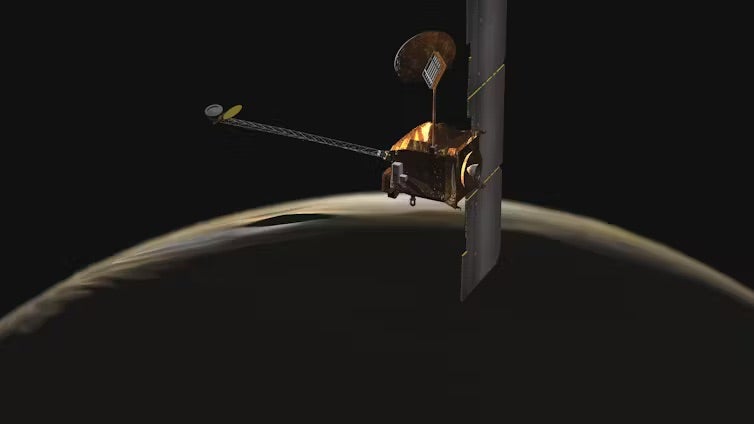

According to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and 1972 Liability Convention – both adopted by the United Nations – this would be a government-to-government issue. The treaties declare that states are internationally responsible and liable for any damage caused by a spacecraft – even if the damage was caused by a private company from that state. According to these laws, your country wouldn’t even need to prove that someone had done something wrong if a space object or its component parts caused damage on the surface of the Earth or to normal aircraft in flight.

Basically, if a piece of space junk from China landed on your house, your own country’s government would make a claim for compensation through diplomatic channels and then pay you – if they chose to make the claim at all.

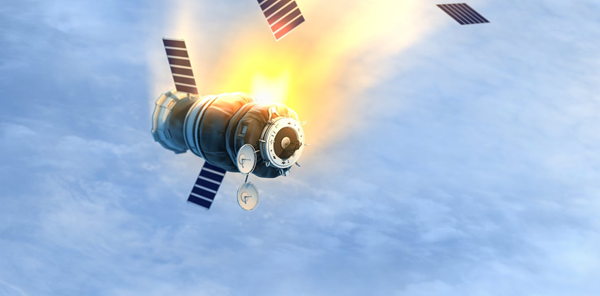

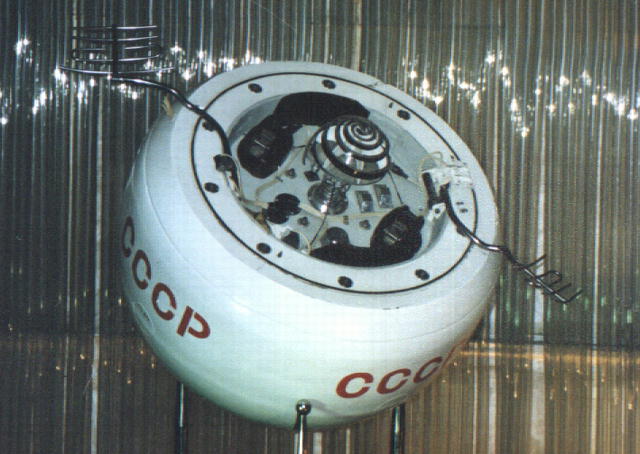

While the chances are slim to none that a broken satellite will land on your house, space debris has crashed onto land. In 1978, the Soviet Cosmos 954 satellite fell into a barren region of Canada’s Northwest Territories. When it crashed, it spread radioactive debris from its onboard nuclear reactor over a wide swath of land. A joint Canadian-American team began a cleanup effort that cost over CAD$14 million (US$11.5 million). The Canadians requested CAD$6 million from the Soviet Union, but the Soviets paid only CAD$3 million in the final settlement.

This was the first – and only – time the Liability Convention has been used when a spacecraft from one country has crashed in another. When the Liability Convention was put into use in this context, four governing norms emerged. Countries have a duty to: warn other governments about debris; provide any information they could about an impending crash; clean up any damage caused by the craft; and compensate your government for any injuries that might have resulted.

There have been other instances where space junk has crashed back to Earth – most notably when Skylab, a U.S. space station, fell and broke up over the Indian Ocean and uninhabited parts of Western Australia in 1979. A local government jokingly fined NASA AUS$400 (US$311) for littering – a fine that NASA ignored, though it was eventually paid by an American radio host in 2009. But despite this and other incidences, Canada remains the only country to put the Liability Convention to use.

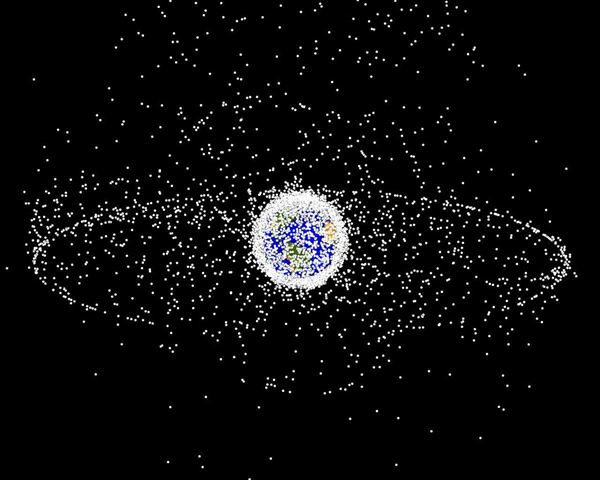

However, if you owned a small orbiting satellite that got hit by a piece of space junk, you and your government would have to prove who was at fault. Currently, though, there is no globally coordinated space traffic management system. With tens of thousands of tracked pieces of debris in orbit – and multitudes of smaller, untrackable pieces, figuring out what destroyed your satellite would be a very difficult thing to do.

Space pollution is the bigger problem

Current space law has worked so far because the issues have been few and far between and have been dealt with diplomatically. As more and more spacecraft take flight, the risks to property or life will inevitably increase and the Liability Convention may get more use.

But risks to life and property are not the only concerns about a busy sky. While launch providers, satellite operators and insurance companies care about the problem of space debris for its effect on space operations, space sustainability advocates argue that the environment of space has value itself and faces a much greater risk of harm than individuals on Earth.

The mainstream view is that degrading the environment on Earth through pollution or mismanagement is bad because of its negative impact on the environment or living beings. The same is true for space, even if there is no clear direct victim or physical harm. In the Cosmos 954 settlement, the Canadians claimed that since the Soviet satellite deposited hazardous radioactive debris in Canadian territory, this constituted “damage to property” within the meaning of the Liability Convention. But, as Article 2 of the Outer Space Treaty declares that no state can own outer space or celestial bodies, it is not clear whether this interpretation would apply in the event of harm to objects in space. Space is shaping up to be a new frontier on which the tragedy of the commons can play out.

Removing from orbit existing large objects that could collide with one another would be a great place for governments to start. But if the United Nations or governments agreed on laws that define legal consequences for creating space debris in the first place and punishment for not following best practices, this could help mitigate future pollution of the space environment.

Such laws would not need to be invented from scratch. The 2007 United Nations Space Debris Mitigation guidelines already address the issue of debris prevention. While some countries have transferred these guidelines into national regulations, worldwide implementation is still pending, and there are no legal consequences for noncompliance.

The chances of a person being killed by a falling satellite are close to zero. On the off chance it does happen, current space law provides a pretty good framework for dealing with such an event. But just like during the early 20th century on Earth, current laws are focusing on the individual and ignoring the bigger picture of the environment – albeit a cold, dark and unfamiliar one. Adapting and enforcing space law so that it prevents and deters actors from polluting the space environment – and holds them accountable if they break these laws – could help avoid a trash-filled sky.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 17, 2021. It has been updated to clarify the history of falling space debris.This story was originally published on the Conversation. Read the original here.