Key Takeaways:

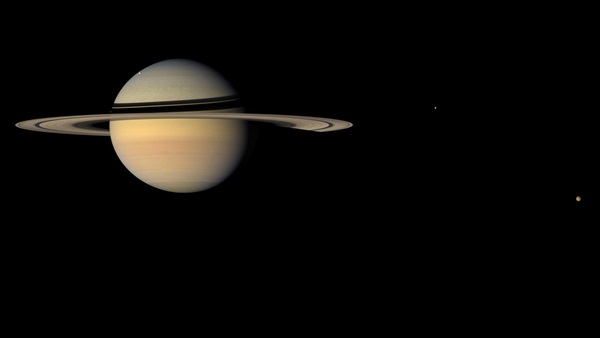

In a paper accepted November 28 to the journal Icarus, researchers from the Planetary Science Institute, the University of Arizona, NASA Ames Research Center, and the U.S. Geological survey report their measurements of isotope ratios in the Saturn system. Isotopes are atoms of a single element with the same number of protons and electrons, but differing numbers of neutrons. Studying the abundance of certain isotopes helps astronomers piece together an object’s history. Some isotopes were more or less common, particularly in certain areas of the solar nebula as it formed planets; others are more likely to stick around or appear after processes such as heating or evaporation. These researchers found that, based on spectroscopic observations of the Saturn system from Cassini, the water in Saturn’s rings and moons is surprisingly like the water on Earth — an unexpected result, given their disparate locations. Even stranger, the water on Saturn’s moon Phoebe (and only Phoebe) is unlike the rest of the water in the Saturn system, suggesting it formed even farther out in the solar nebula, rather than in place around the ringed planet.

Earthlike water

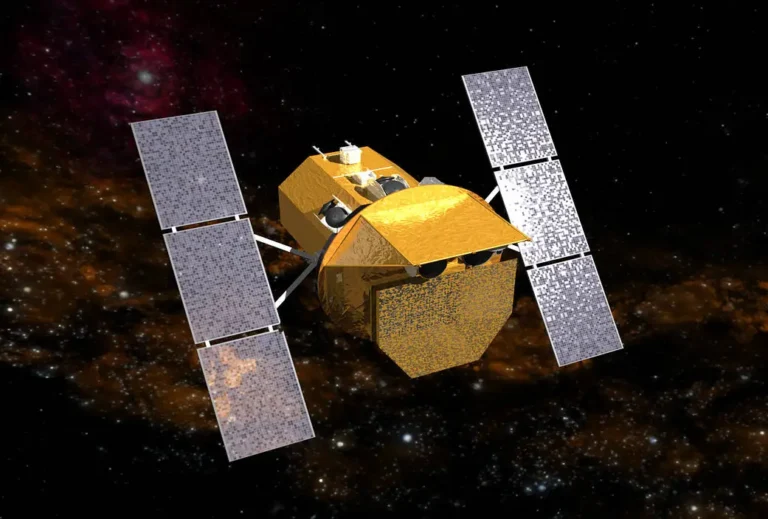

To make these discoveries, the team developed a new way to measure isotope abundances in the readings taken by Cassini’s Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS). In particular, they studied the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen (D/H) in the water in the Saturn system. Deuterium is an isotope of hydrogen with one proton and one neutron in its nucleus; D2O, which is water that contains deuterium instead of hydrogen, is commonly known as heavy water because of the added mass from the extra neutrons.

Each spectrum taken by VIMS breaks the light reflected from the surface of Saturn, its rings, or its moons into its constituent parts to identify the fingerprints of the elements contained within them. Based on comparison of laboratory spectra with the VIMS results, the team discovered the bulk of the Saturn system’s water, including the water in the planet’s rings and on its moons (except Phoebe), has a D/H ratio similar to terrestrial water. However, our current models for the formation of the solar system state that the D/H ratio farther out in the solar system should be higher than closer in; if Earth formed close to the Sun and Saturn far from it, why is their water so similar?

According to the team, the similarities indicate that the same type of water may have been found in the inner and outer solar system during its formation, which would require us to change our current models. “The terrestrial-like D/H of Saturn’s rings and satellites may indicate a similar water source for the inner and outer solar system, or at least a change in models where the D/H varies less from inner to outer solar system, less than a factor of two from Earth to Saturn,” the paper states.

One oddball

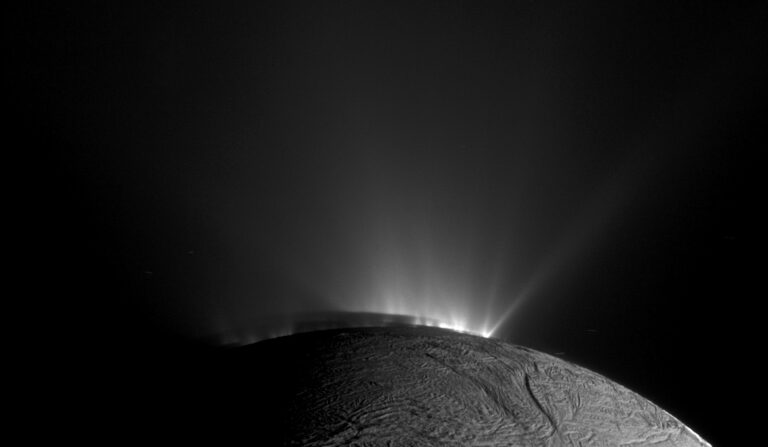

On Phoebe, the D/H ratio “is the highest value yet measured in the solar system, implying an origin in the cold outer Solar System far beyond Saturn,” said the paper’s first author, Roger Clark of the Planetary Science Institute, in a press release. In other words, Phoebe likely formed elsewhere, much farther from the Sun, and later became a part of the Saturn system through gravitational capture.

The only other way for Phoebe to have such a high D/H ratio, the paper says, is for processes to have enhanced its present-day deuterium supply over time. These processes, however, “[require] Phoebe to have present-day characteristics similar to objects that are composed primarily of rock and organics, which is not what we observe,” the paper states.

Too much deuterium isn’t the only thing that makes Phoebe odd. In addition to measuring the D/H ratio, the researchers were also able to measure a different isotopic ratio — that of carbon-13 (13C) to carbon-12 (12C) — in the carbon dioxide on both Phoebe and Iapetus (the only two worlds with enough carbon dioxide to make the measurement). While Iapetus’ 13C/12C ratio closely matches Earth’s, Phoebe’s ratio is also skewed, showing five times more 13C than the “normal” 12C. This oddity, too, points toward an origin for the small moon farther out in the solar system, with different processes responsible for the carbon dioxide on the two moons. Also of note is the fact that, although dust from Phoebe is known to coat the leading side of Iapetus, “if there were any CO2 in the Phoebe dust on ejection from Phoebe, it is apparently lost on its way from Phoebe to Iapetus,” the paper states.

So, what do astronomers do with this unexpected information? In addition to potentially updating solar system formation models to more accurately represent reality, getting measurements of the isotope ratios farther out in the solar system can bolster the case for Phoebe’s far-out formation, as well as paint a clearer picture of the distribution of hydrogen, carbon, and other elements (and their isotopes) throughout our early solar nebula. “D/H measurements on the icy satellites of Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune are needed to show the larger trends in the solar system,” the paper states, “but such measurements can only be done above the Earth’s atmosphere.” Fortunately, with our army of current and upcoming space telescopes and remote missions — including Europa Clipper, on which Clark is a co-investigator — those measurements may soon become a reality.