Key Takeaways:

- The article outlines the challenge of discerning Theta1 Orionis and Theta2 Orionis as separate entities using only the unaided eye, with their combined apparent magnitudes approximated at the 5th magnitude.

- Theta1 Orionis represents the collective light of the Trapezium cluster's four main stars, while Theta2 Orionis comprises Theta2 A and B, which appear as a single object to the unaided eye, with Theta1 and Theta2 A separated by 2.2 arcminutes.

- Factors complicating this observational feat include the inherent dimness of the stars, the variable brightness of Theta1 Orionis due to eclipsing binary components, and the surrounding Orion Nebula's glow, which diminishes the contrast necessary for naked-eye resolution.

- Strategies to enhance visibility include observing during a First Quarter Moon or twilight conditions to reduce the impact of nebular interference, and navigating the trade-off between direct vision for resolution and averted vision for light sensitivity.

Up for an extreme challenge? One with your unaided eyes? If so, buckle up for this one: splitting Theta1 (θ1) Orionis and Theta2 (θ2) Orionis without optical aid. For some, this challenge may be “out of sight,” but there’s only one way to find out.

First, some background

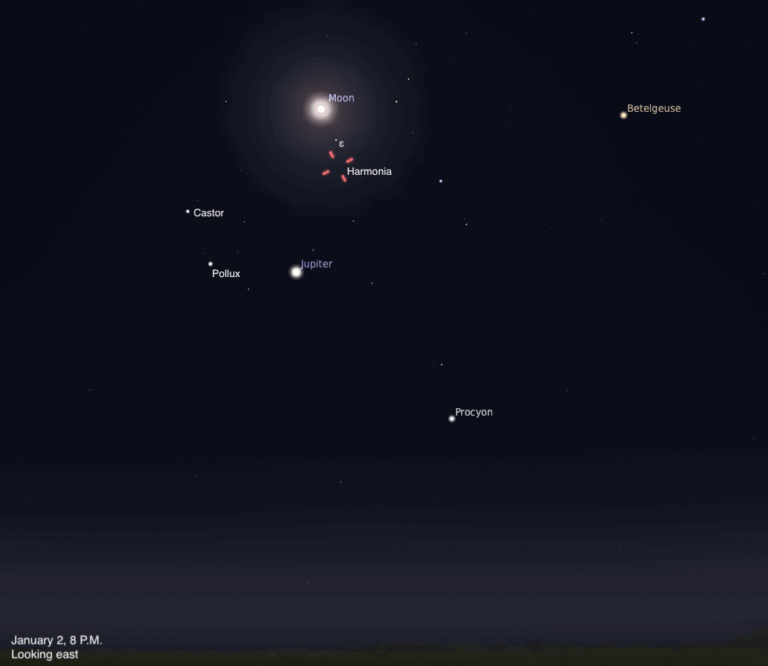

Theta1 and Theta2 Orionis are two multiple-star systems within the Orion Nebula (M42). Theta1 includes several stars; the four brightest comprise the Trapezium star cluster at the heart of M42. To the unaided eye, these four stars shine roughly as a solitary 5th-magnitude star. The magnitude is not exact, because the Trapezium’s two brightest components (Theta1 Orionis A and B) are eclipsing binary stars. Theta1 Orionis A dips in brightness by 1 magnitude every 65 days in an eclipse lasting over 20 hours; Theta1 Orionis B dips in brightness by 1 magnitude every 6.5 days over 16 hours. So, you’re likely to catch the Trapezium stars when they are close to their brightest, but it’s not guaranteed.

Theta2 Orionis A shines at magnitude 5.0 but, to the unaided eye, its light combines with neighboring Theta2 Orionis B (magnitude 6.2 and about 1′ away), giving it an extra visual kick. (Theta2 Ori C, the other component of Theta2 Ori, is below naked-eye visibility at 8th magnitude.) So, in essence, the challenge involves separating two 5th-magnitude multiple stars 2.2′ apart. That’s a tiny gap. Most people find splitting the famous Double Double in Lyra a challenge; its two 4th-magnitude companions are wider apart (3.5′) and 0.5 magnitude brighter than the Theta stars.

What’s more, anyone trying to split Orion’s Theta stars under a dark sky will discover a visual impediment: the surrounding Orion Nebula, whose glow lowers the contrast of the gap between the two stars.

The Theta challenge

Scott Harrington of Evening Shade, Arkansas, brought the unaided Theta challenge to my attention after he succeeded in splitting the pair. He writes in an email, “I doubt I could ever do any pair of stars that are closer together with the naked eye.”

Harrington had known for some time that his friend Lauren Herrington had already resolved the Thetas with her unaided eyes. But he hadn’t been able to do it under his rural country skies, finding that the surrounding nebula completely overpowered the stars. In January 2022, however, he found the nebula greatly diminished under the light of the Full Moon and tried again. Using a chimney to block the Moon, he saw the two Theta stars strongly elongated and “for moments I could split them,” he writes.

Herrington’s observation is especially revealing and speaks volumes about her visual acuity. “I’ve never really been able to see the Orion Nebula with the naked eye,” she writes, “even from very dark skies. All I can see is the double star of Theta Orionis, which is well separated (a little dark lane in the middle). I’ve often noticed it because the canted double of Theta makes a fun pair with the wider and brighter double of Iota (ι) Orionis just to the south.” Her confidence is refreshing.

Direct versus averted vision

Seeing and resolving the Theta pair requires a tricky trade-off between averted and direct vision. It’s easiest to resolve double stars when looking at them directly and intently, but your eye will be less sensitive to their light than with averted vision and may lose sight of them entirely. In his The Nature of Light and Color in the Open Air, the late Dutch astronomer Marcel Minnaert wrote, “To me personally, even the stars of the fourth magnitude become invisible, whereas those of the third magnitude remain visible.”

While this limit may vary from observer to observer, it shows the difficulty of the task ahead, especially if you live under a dark sky where the nebula interferes. But dark-sky observers don’t have to wait for a Full Moon — a First Quarter Moon is better, as it not only adequately diminishes the nebula’s light but also allows the dim Theta stars to shine through more conspicuously.

You can also wait for the Theta stars to emerge from twilight’s last gleaming (largely nebula-free) and follow them until nightfall. Twilight is, and always has been, the best time to separate multiple stars. Good luck, and, as always, let me know how you fare at someara31@gmail.com.