Key Takeaways:

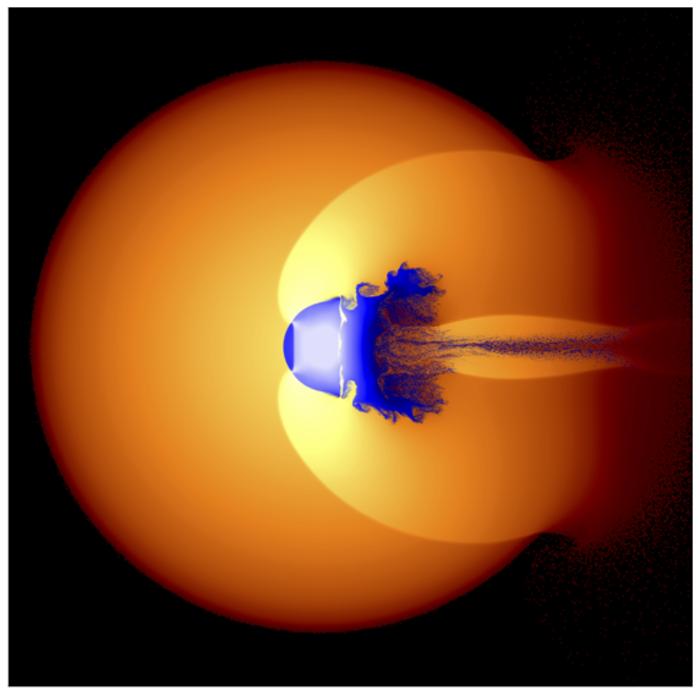

An imaginary robotic lander eclipses the Sun as it fires retrorockets in preparation for touching down on a comet. The comet’s surface, though icy, appears dark due to a widespread coating of hydrocarbons. The image was designed for the 2004 book Futures: 50 Years in Space (Harper Design), by Hardy and Sir Patrick Moore.

Painters have played a significant but underappreciated role in our exploration of the worlds in our solar system.

Scientists tend to specialize in narrow aspects of reality — spectroscopy, photos, petrology — all represented in terms of numerical measurements. But what do these numbers mean in terms of the human experience? It is artists who synthesize those results to visualize what each world is truly like.

In the early 1900s, the French artist and astronomy popularizer Lucien Rudaux (1874–1947) published numerous paintings showing surface environments on our neighbor worlds, based on then-current scientific knowledge. His 1937 book Sur les Autres Mondes (On Other Worlds) included many such paintings, some reproduced in color. And thanks to the efforts of a number of enthusiasts including myself, Rudaux’s book was republished in 1990 in a facsimile edition by the original Paris publisher, Larousse.

Two of the many telescopes situated atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii sit beneath a beautiful sunset as the astronomers stationed within anticipate clear skies for spectacular viewing of the universe. This painting is the third in a series of images of U.S. observatories and part of a larger project the artist is currently working on.

Rudaux’s book enthused an American artist, Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986), who was a leading special-effects artist in Hollywood, having painted backdrops in famous films such as Citizen Kane. In 1944, the popular weekly LIFE magazine published a series of paintings by Bonestell, showing the planet Saturn as seen from its various satellites.

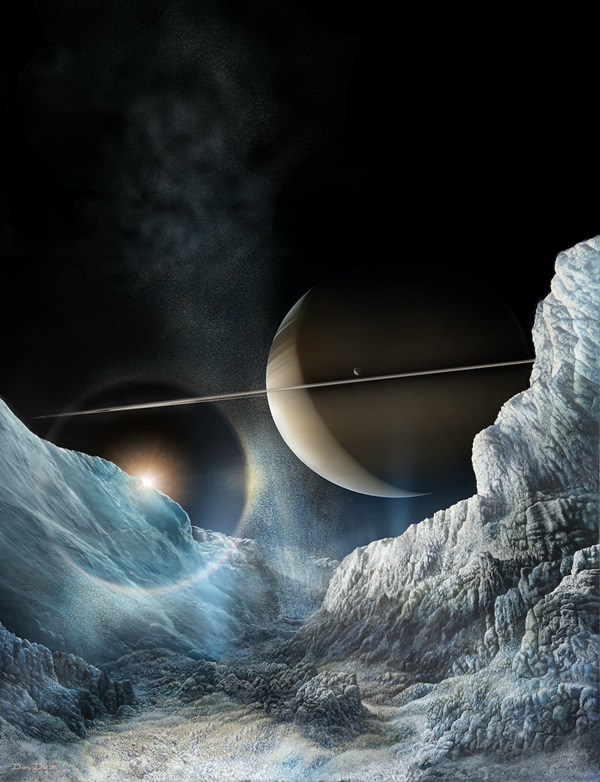

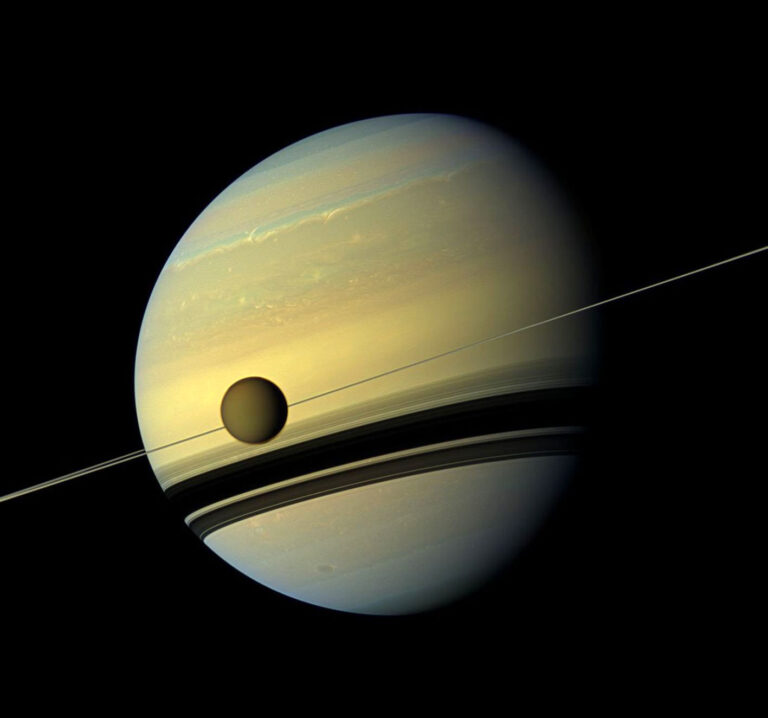

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan — which is larger than the planet Mercury — presented an interesting challenge. Astronomer Gerard Kuiper had recently confirmed earlier suspicions that Titan had a substantial atmosphere. (It is, in fact, the only moon in the solar system to have one.) Bonestell saw the opportunity to paint a moonscape without a black sky and produced a famous painting showing Saturn in a blue sky over an icy landscape.

But the view from Titan continued to challenge scientists as well as artists. Decades of scientific progress following Bonestell’s painting indicated that Titan’s atmosphere produces not a clear blue sky, but a cloudy haze so thick that Saturn might be rarely, if ever, visible from the surface.

This story is just one example of the importance of astronomical art. Scientists publish their work in peer-reviewed journals, but astronomical realist painters translate the results to show what distant worlds would look like if we could be there.

Here’s another example: In 1949, Bonestell illustrated a world-changing book, The Conquest of Space, with text by science popularizer Willy Ley. The book’s paintings included new landscapes on various planets, created based on consultations with scientists during preparation of the book. Its cover showed a sleek, silver rocket and astronauts on the Moon. (As astronomical artist and historian Ron Miller has said, “That’s the way rockets were supposed to look!”) Many of the engineers and scientists who put the Apollo astronauts on the Moon were inspired by that book as teenagers. The great science-fiction author Jules Verne is often quoted as writing, “Anything one man can imagine, other men can make real.” Bonestell’s paintings showed the dream and the Apollo engineers made it a reality.

Ludek Pesek (1919–1999) was another pioneer of astronomical art. His work is widely known in Europe. The Czech artist was vacationing in Switzerland in 1968 when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, prompting him to remain in Switzerland for the rest of his life. His paintings, while mostly realistic, sometimes included touches of whimsy. I was fortunate to visit Pesek and his wife in Switzerland, and in their home I noted a view of a lunar hillside showing a large rock that had rolled toward the viewer, leaving a visible track behind it — but the boulder appeared to have been stopped in the foreground by a tiny flower.

The artistic movement started by Rudaux, Bonestell, and Pesek might be called astronomical realism. Each painting (and this includes terrestrial landscape paintings, since Earth is a planet, too) challenges the artist to depict reality — not as it is expected or as artists would like it to be, but as it actually exists.

Shortly after arriving on the Red Planet, NASA’s newest Mars rover, Perseverance, set down the tiny robotic helicopter Ingenuity. Mars Exploration Rover project manager John Callas described this painting, which depicts that moment, as showing the maternal relationship between the rover and its companion. The artist remains awestruck by the surprisingly heartfelt emotional undertones that connect these two amazing machines.

This triangular relationship of nature, art, and science is well demonstrated by Earth’s blue sky. Its hue is explained through Rayleigh scattering — the preferential scattering of blue light by microscopic particles in the atmosphere, discovered by English scientist Lord Rayleigh in the late 1800s. But nearly 400 years earlier, the painter and scientist Leonardo da Vinci pointed out in a booklet on painting that a building or mountain in the distance has paler shadows and bluer color than one in the foreground. He concluded correctly that sunlit air adds blue light. The greater the distance, the more blue light appears. Rayleigh worked out the physics, allowing predictions about the blue light, but long before he did, da Vinci had described the human perception of the effect, which painters call atmospheric perspective.

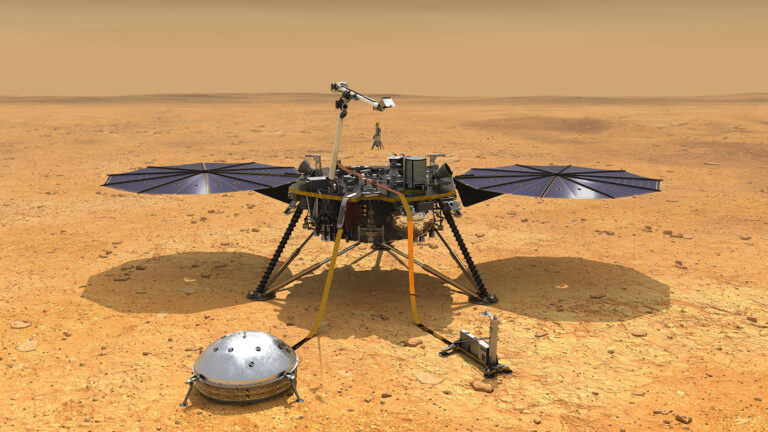

Each planet offers a unique challenge. Mars might seem easy to paint because of the abundant imagery from landers and rovers, as well as the presence of similar landscapes on Earth. However, determining the actual colors that would be perceived by a human on the surface has been a problem from the start. As I witnessed while reporting for Astronomy in 1976, NASA’s initial press release landscape from the first successful martian lander, Viking 1, showed — as then expected — a blue sky. But after some hours, the Viking imaging team realized that reddish colors dominated not only the landscape but also the sky. The problem arose from incorrectly balancing blue filter and red filter signals from the lander’s camera.

Jets of water erupt into space and fall as snow in this view from inside one of the famous tiger-stripe features near the south pole of Enceladus. Fellow satellite Mimas transits Saturn in the background. The image shows the complex features that might form when ice particles launched at high velocity rain down in a low-gravity environment.

Each planet offers a unique challenge. Mars might seem easy to paint because of the abundant imagery from landers and rovers, as well as the presence of similar landscapes on Earth. However, determining the actual colors that would be perceived by a human on the surface has been a problem from the start. As I witnessed while reporting for Astronomy in 1976, NASA’s initial press release landscape from the first successful martian lander, Viking 1, showed — as then expected — a blue sky. But after some hours, the Viking imaging team realized that reddish colors dominated not only the landscape but also the sky. The problem arose from incorrectly balancing blue filter and red filter signals from the lander’s camera.

Later landers and rovers have suggested the martian sky color varies with the dust content in the air. I’ve witnessed a similar shift in Arizona, from blue to tan, during dust storms. To confuse matters further, some martian images are deliberately altered toward bluer colors, so that geologists can get a sense of martian rock formations in lighting more like that on Earth, under our blue sky. So, the internet is full of Mars images with different color balances, including attempted true-color images. What does Mars really look like to a human visitor? We have yet to find out.

One lesson we should take away from all this is not to throw out older paintings because they might be scientifically wrong. Instead, they preserve an important record of what we as human beings knew about our solar system at the time they were painted. And what we have learned along the way is that when it comes to exploring our solar system, painters and scientists have a fascinating and productive relationship!

A small robotic rover travels the trackless wastes of Europa, bathed in the dim glow of ice and snow that have been excited by intense radiation from nearby Jupiter. The radiation will severely limit the functional lifetime of any craft sent to explore the icy moon, as energetic particles bombard onboard computers and other delicate electronics, quickly degrading them.

A cloudburst of methane rain floods a river as it carves a canyon through layers of reddish hydrocarbon-tainted water ice on Titan. Astronomers have observed convective clouds in the moon’s southern hemisphere during its summer; rainfall from such clouds could be substantial. Meanwhile, images from Cassini reveal flowing river channels of liquid methane and ethane feeding lakes. This moon is so cold that water ice plays the role of solid rock.

Saturn dominates the view of an imaginary observer standing on the surface of a dormant comet as it passes by the mighty ringed planet. The close flyby will impart a gravity boost that will send the small world into the inner solar system. And as it nears the Sun, it will grow a coma and tail, sprouting into an active comet for earthbound skywatchers to enjoy.

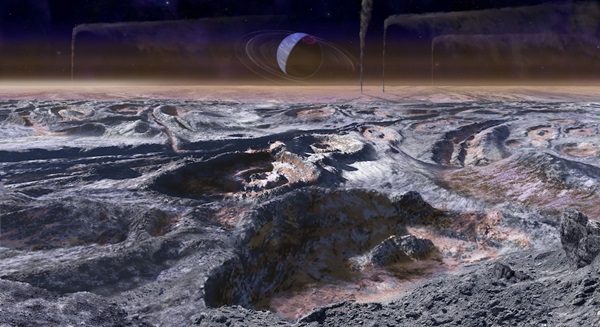

Triton’s mysterious cantaloupe terrain is unique in our solar system. Its melon-rind appearance comes from depressions called cavi. This region sits at the edge of Triton’s pink nitrogen-ice polar cap and is thought to result from a combination of erosion, sublimation, and internal forces.

NASA’s round DAVINCI probe sits on the surface of Venus, its mission of sampling the planet’s clouds from top to bottom complete. DAVINCI is currently under development for launch in 2029. Its descent will mark the first U.S. mission in four decades to enter the atmosphere of Earth’s sister planet.

This scene shows the surface of Titan only moments after a methane rainfall has passed. Rivulets of liquid methane drain into methane streams that eventually lead to a larger methane sea. On Titan, the weather is driven by cycles of methane and ethane, much like the more familiar water cycle that occurs on Earth.

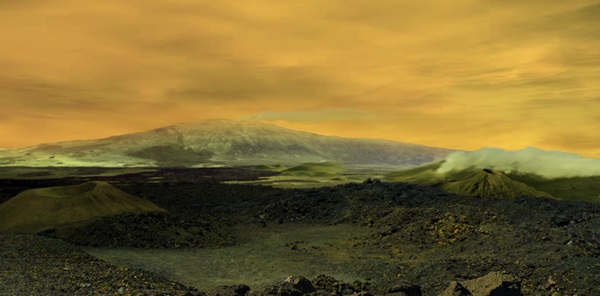

Maat Mons is the tallest volcano on Venus, topping out 26,250 feet (8,000 m) above Venus’ mean surface level. This digital image shows it as an active volcano with ash rising from the summit, surrounded by lava flows. Steam eruptions are not possible on Venus, due to its surface temperature of 900 degrees Fahrenheit (475 degrees Celsius). Colors and lighting for this image were sourced from Soviet Venera images.