Astronomy enthusiasts today have an astounding array of observing aids available at their fingertips. From computer simulations to phone and tablet apps, some may say there is little need for paper maps or guidebooks to the cosmos.

Yet there is something satisfying and tactile about thumbing through a classic observing guide in preparation for a night under the stars. Exploring some of these resources, past and present, can be enjoyable and useful even in the digital age.

Geography of the Heavens

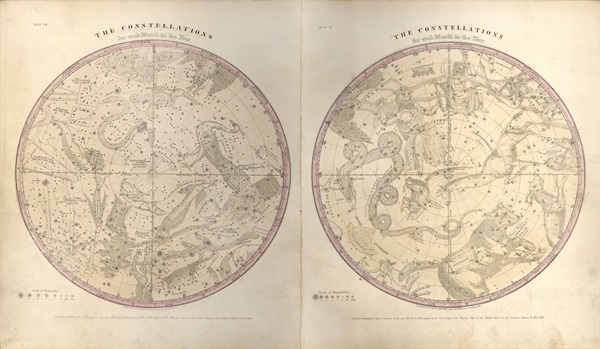

Little information is available on the life of the author of one of astronomy’s predominant classical observing guides. Elijah Burritt was a teacher who likely saw a need for better textbooks for observers. First published in 1833, the six maps of his atlas and accompanying guidebook, Geography of the Heavens, fulfilled this need, selling more than 300,000 copies. Some 200 years after first going to press, his maps are still being reproduced and sold.

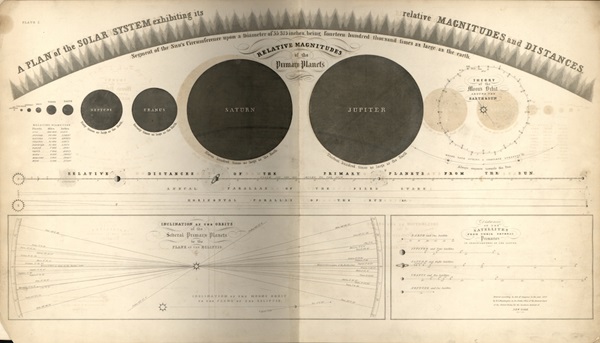

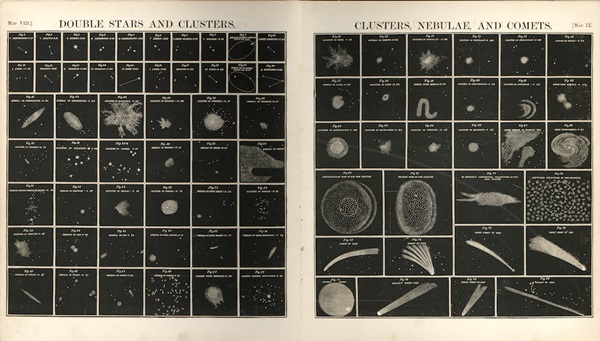

The Wonders of the Telescope

Observing guides truly blossomed in the 19th century. Telescopes were becoming more affordable and the study of astronomy had taken on an allure beyond its use for navigation and almanacs. The Wonders of the Telescope, published in 1805, promises “a display of the wonders of the heavens and of the system of the universe.” It has all you need to explore the night sky. There are maps and fold-out charts, along with detailed descriptions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and even a few deep-sky objects. This little book helped set the standard form for the next 200 years of observing guides.

Of opera-glasses and telescopes

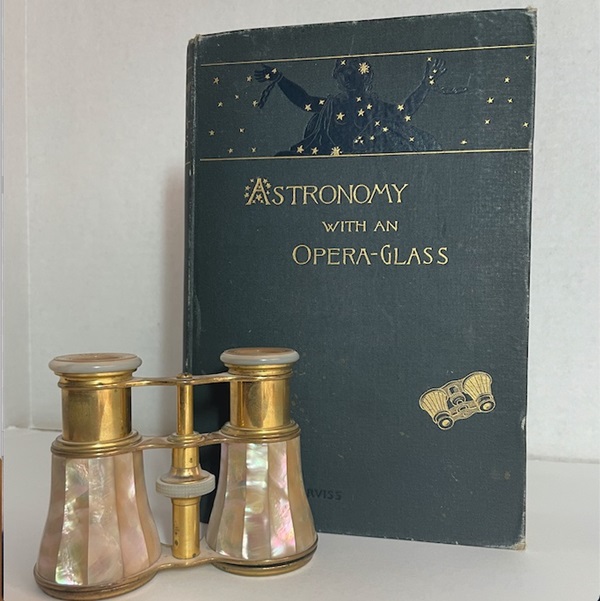

When I was about 10 years old, I found a battered copy of Astronomy With an Opera-Glass, by Garrett P. Serviss, high up on a shelf in our town’s old Carnegie library. I later discovered that Serviss had written a series of astronomy books, including three others that are observing guides. At the end of the 19th century, he began his Urania Lectures — an early multimedia event. With backing from Andrew Carnegie, Serviss took the show on the road, popularizing astronomy and science for the masses.

When he settled down, he wrote books on all aspects of astronomy, science fiction, and even relativity. In addition to with Astronomy With an Opera-Glass, he also wrote Pleasures of the Telescope. His style is delightfully illustrative of attitudes in the 19th century and wonderfully informative. One of my favorite quotes from his writing, “But let us sit here in the star light, for the night is balmy, and talk about Arcturus,” shows how he is truly at ease with the sky. Some of the information is dated, but you can certainly learn your way around the sky with these delightful books. And both books feature star charts that are still useful. I have had my own copies of these books for years. The star maps and descriptions of celestial wonders are fascinating, and I continue to use these guides for observing.

Norton’s Star Atlas

For many 20th-century astronomy enthusiasts, amateur or professional, one guidebook defines the era: Norton’s Star Atlas. The Atlas first appeared in 1910 — the same year its creator, Arthur Philip Norton, became a member of the British Astronomical Association. Born in 1876, he was as a young man given an old family telescope, which sparked a lifelong interest in astronomy and science. Norton spent his career as a schoolmaster teaching science and pursuing his love of the sky as an amateur. His guidebook has become a touchstone for observers.

The original 1910 guidebook was called The Star Atlas and Reference Book. It was so popular that a second edition was published during World War I, even though there was a national paper shortage in Britain. By the 1921 third edition, the familiar star charts and reference layout were well established. An interesting feature of the main star maps is Norton’s use of gores: If sections of a globe are cut off into individual maps, they look like truncated ovals. By using this method, Norton was able to avoid some of the distortions that occur with other map projections.

Over the years, Norton’s Star Atlas has evolved. The Atlas has always had notes on astronomical terms, planets, stars, nebulae, and more. With each edition, these sections have been updated and enlarged. The star maps have also been updated for the changing star coordinates caused by precession. The most noticeable change in the Atlas occurred in 1933. Before 1930, constellation boundaries had not been formalized. Constellations and their stars appeared contained by random wavy lines on sky maps. There was some agreement as to what stars belonged to each constellation, but there were also possible variations, depending on who was making the maps. The first four editions of the Atlas have the old-style boundaries. In 1930, the International Astronomical Union formalized constellation outlines by following lines of right ascension and declination to set the boundaries. Norton brought his maps into the new era for the fifth edition by using these precise boundaries. After more than 100 years and 20 editions later, this beloved observing guide is still a valuable aid to many observers. I imagine that Norton would certainly be pleased and perhaps a little surprised.

Field Book of the Skies

The Field Book of the Skies, by William T. Olcott, was published in 1929 and quickly found a following among stargazers. Olcott arranged his guide by season. The charts are simple and do not have coordinate references. Each constellation section gives location and mythology information. Olcott describes what can be seen with the unaided eye and field glasses, all with an accompanying chart. Then, he provides a page with objects for telescopes and an expanded chart to find them. The book also has information for beginners, a section on the planets, and basic charts of the Moon during various phases. It’s this layout that proved so popular with the public.

Olcott originally intended to become a lawyer, but then he fell in love with a young woman named Clara Hyde. She introduced him to stargazing, which set him on a path of observing and publishing. Olcott was fascinated with the mythology of the sky and published several books on the subject. He was a founding member of the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). In the 1950s, AAVSO director Margaret Mayall and her husband Robert oversaw the fourth edition of the Field Book, which remained in print for another two decades. Touchingly, Olcott dedicated the Field Book of the Skies to his wife Clara.

Exploring with binoculars

Scanning the stars with binoculars is a wonderful way to relax on a clear night. Exploring the Night Sky With Binoculars, by Patrick Moore, published in 1996, has earned a place among the classics for observers with low-power instruments. Moore was the ultimate amateur astronomer. He never received a degree in astronomy but turned his interest and intellect into a lifelong career. Moore’s book for binocular stargazing is straightforward and easy to use — a hallmark of a classic. The constellations are presented in alphabetical order, but the charts are reminiscent of Olcott’s Field Book of the Skies. Moore is a master at clarity in providing guidance to the wonders of each constellation. After four editions, this is still an outstanding guidebook.

Guideposts to the Stars

Howard Shapley described our next author as “the world’s greatest non-professional astronomer.” True to Shapley’s description, Leslie Peltier discovered Nova Herculis 1963 as well as a few other comets and novae. Published in 1972, Peltier’s Guideposts to the Stars: Exploring the Skies Throughout the Year provides easy reading to prepare for a night’s observing. One of the book’s delights are the drawings and charts that accompany the descriptions of how to find stars and constellations. On each two-page spread is a drawing of the sky that shows the horizon and a house for scale. On the facing page is a chart of the same area, giving details of what can be seen. This sense of scale helps steer the observer on their journey.

Precious pages

What makes an observing guide a classic can be quite subjective. No one book is going to cover every topic or area you may need for a night’s observing. If you have been watching the sky throughout your life as I have, though, there are a few books you will always want on your shelf to plan your next evening under the stars.

Notable mentions

Defining what makes a guide a classic can be difficult, and there are plenty of other books potentially deserving of that title. Some additional selections are:

- The Peterson Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, by Donald Menzel

- The Constellations, by Lloyd Motz and Carol Nathanson

- The Cambridge Guide to the Constellations, by Michael E. Bakich

Classics for kids

I have a soft spot for a few guidebooks from when I was a kid. Here are some of my favorites:

- Find the Constellations, by H.A. Rey

- The Stars: A New Way to See Them, by H.A. Rey

- Golden Nature Guide’s Stars, by Herbert Zim and Robert Baker

- The Observer’s Book of Astronomy, by Patrick Moore