This isn’t a criticism. In three northeastern states, the most rural possible location is still within 30 miles (50 kilometers) of a city, producing bright glows in multiple directions. This is a central issue and battle cry for organizations like the International Dark-Sky Association, which tirelessly tries to limit waste lighting and unshielded yard lights.

Since I also lead annual overseas trips to perfect sites in deserts and such, I’m keenly aware of the dark skies issue, to which we can all relate. Strangely enough, in all these years, it’s never been this column’s main topic. But it now comes vividly to mind because of something that happened last night.

It was midnight, and I couldn’t sleep, so I walked out to the meadow behind my house in a bathrobe and bare feet. The cold dewy grass was uncomfortable, but the moonless sky erased all body-awareness. Normally my rural area has good — but not superb — skies, yet something odd unfolded last night. Maybe it was the extraordinarily dry air. In any case, I was given a reminder of the dramatic difference between skies that are good and those that are outstanding.

Outstanding conditions provide an unusual experience. A strange one, truth be told. The firmament becomes so amazing — and I’m talking naked-eye — that it’s worth time and expense to travel to experience it. We all know where such conditions may be found. Southern Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The western states far from any town. The White Mountains of New Hampshire. Upstate New York’s Adirondacks. I’d love to hear about your favorites.

Outside the U.S., many abound. Chile’s northern half. Australia’s Outback. The Sahara. The Persian desert southeast of Isfahan — alas, not a good travel idea these days, which is a shame because the Iranians generally like Americans and love astronomy. Here’s a quick guide to what happens.

OUTSTANDING CONDITIONS PROVIDE AN UNUSUAL EXPERIENCE.

In the near-city suburbs, about 130 stars appear across the sky at any given time, but there’s no sign of the Milky Way.

In the farther-out suburbs, the Milky Way appears dimly. The Little Dipper has five or six stars.

In good rural regions, the Little Dipper displays all seven stars and the Milky Way is clear, its rifts showing conspicuously. The Andromeda Galaxy (M31) is obvious.

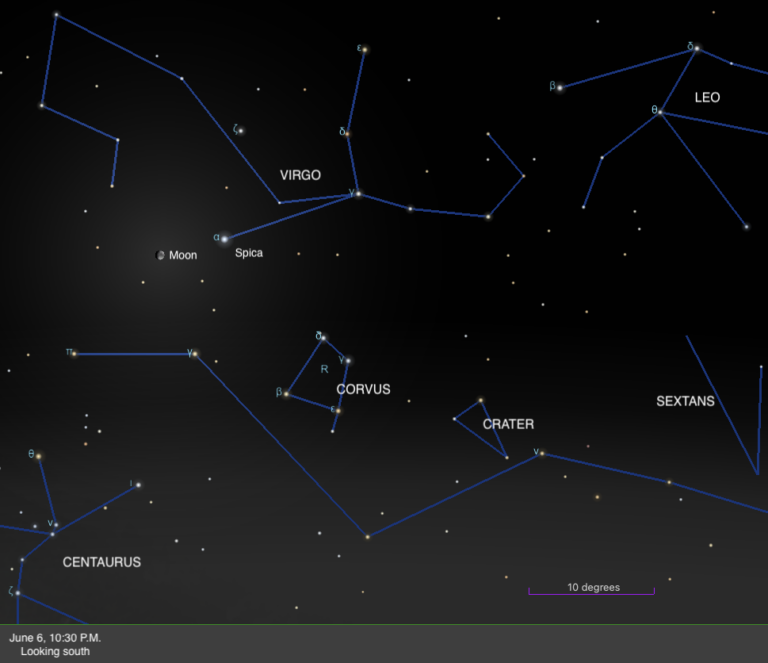

In very good rural skies, Orion’s Belt is embedded in innumerable faint stars, the Milky Way is the most prominent feature of the heavens, and the Hercules globular M13 is steady. It doesn’t merely come and go.

Now here’s the difference as we jump up to outstanding skies. It’s not subtle. In such conditions, constellations are initially confusing because so many stars pepper the scenery. The Milky Way “pops” and totally dominates the sky dome. It casts shadows. It does not have rifts or splits. Instead, intricate inky nebulae become the night’s most prominent feature. Black crablike tentacles of abstract art — numerous filaments and sharp-edged blotches — form distinct cameos in front of the brilliant Milky Way. These ebony structures, I rediscovered last night, are so detailed and 3-D-seeming, they’re the most in-your-face aspect of the night.

If Andromeda is up, the large round Pinwheel Galaxy (M33) dimly comes and goes in its vicinity. Fourteen Pleiads can be counted, though three may blink in and out. This is the sky nature designed. It is far superior to the view astronauts get in space. Up there, stars are dim because of the four thick glass layers in space station portholes, while spacewalkers must peer through visors of polycarbonate plastic.

But these premier earthly skies are not truly black. Air glow, caused mostly by solar ultraviolet, is always present. It bathes the unpolluted countryside with five times more light than all the stars combined. It looks brightest about 10° above the horizon. Unless you’re under a canopy of trees (and what would be the point of that?), it lets you always see well enough not to stub toes, once eyes adapt to the dark.

Ah, what wonder! It’s evocative of whatever got us hooked on astronomy in the beginning. It still awaits. True, these places are often farther away than in the old days. They usually entail time and expense. But not last night, when I got a gift. And who do I thank? Insomnia?

It must be insomnia.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.