With such huge volumes of data comes the need for an increased ability to handle them. That’s where citizen science comes in, filling a unique role to propel science forward.

Zooniverse is a self-proclaimed platform for people-powered research. This unique website connects citizen scientists — you — with professional researchers, to promote collaboration and discovery using vast catalogs of data.

It’s not just astronomy and physics that have benefited from this amazing platform. Zooniverse’s diverse project categories include biology, history, climate science, the arts, medicine, ecology, and the social sciences. If you grow tired of studying transit data from the Kepler space telescope (Exoplanet Explorers: exoplanetexplorers.org) or characterizing glitches in the LIGO instruments to improve gravitational wave detection (Gravity Spy: gravityspy.org), you can easily switch to counting Weddell seals in Antarctica’s Ross Sea (Weddell Seal Count: www.zooniverse.org/projects/slg0808/weddell-seal-count). Or perhaps sorting through fragments of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean texts dating from the 10th to 13th centuries is more your style (Scribes of the Cairo Geniza: www.zooniverse.org/projects/judaicadh/scribes-of-the-cairo-geniza).

Regardless of the projects you choose to explore, you’ll be taking part in scientific research alongside some 1.6 million volunteers around the world. “Zooniverse is inclusive. It’s about discoveries we can make together,” says Chris Lintott, Zooniverse’s founder and principal investigator, and professor of astrophysics at the University of Oxford.

Founded in 2007, Zooniverse is a collaboration between the Adler Planetarium, the University of Oxford, and the broader Citizen Science Alliance. Over the past 10 years, the platform has grown from a single project to over 125 current and completed “zoos” that connect professional researchers with citizen volunteers to produce otherwise unattainable results.

A galaxy zoo

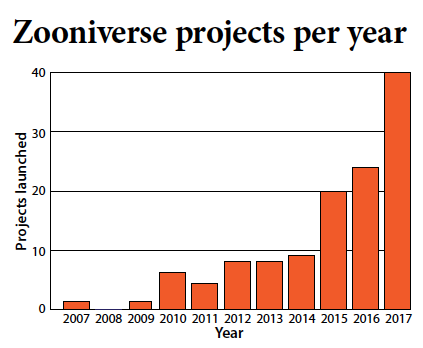

Just like its name, Zooniverse began with a zoo. In 2007, Lintott developed Galaxy Zoo, calling upon volunteers to look at digital images of galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and classify them as spirals, ellipticals, or mergers. There are a lot of galaxies in the universe, posing a challenge for astronomers who need to classify data sets rich with millions of them. When he was a graduate student at Oxford, Kevin Schawinski, an original team member, spent a month doing nothing but classifying galaxies for roughly 12 hours a day, topping out at about 50,000.

In fact, human volunteers can do it better than computers, which can easily get confused or even miss galaxies altogether in images. The human brain is far better at picking out patterns than any computer algorithm yet devised.

That’s the true power behind Zooniverse. “The things that we ask of our volunteers are things that computers are not really good at,” emphasizes Zach Wolfenbarger, a Zooniverse web developer at the Adler Planetarium.

The more volunteers who look at a single galaxy or image, the more likely the resulting classification is to be correct. So if you’re worried about influencing a project’s results because you might misclassify an object, don’t be: Each image you’ll work with is viewed and classified by many people, and as the number of classifications increases, the most common answer grows in statistical significance.

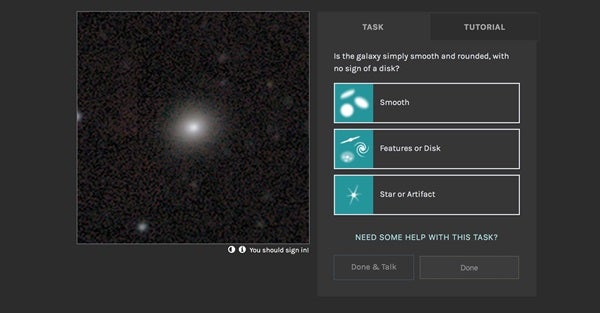

When Galaxy Zoo launched, the response was overwhelming, says Lintott. Within a day, the site was receiving nearly 70,000 classifications per hour. Within a year, more than 50 million classifications had been submitted by over 150,000 participants. And 10 years later, Galaxy Zoo is still running (galaxyzoo.org), albeit with a few changes, including a vastly expanded data set. The tasks volunteers are asked to complete have grown as well, from initially putting galaxies in one of just a few groups to now estimating the roundness or flatness of elliptical galaxies or the number of arms in a spiral galaxy and the size and shape of its bulge.

So far, this sounds like a pretty sweet deal for researchers. After all, why spend hours scouring data yourself when you can get volunteers to do it in their spare time — for free?

But the benefits of the Zooniverse go both ways. Researchers find the help they need to manage large data sets and make new discoveries, and volunteers become part of a community that facilitates exploration, communication, and scientific advancement. Volunteers’ names are listed alongside project leaders’ on discovery papers, and dozens of volunteers are co-authors on articles in which they have participated in the data analysis and discussion. They help moderate online discussion forums for each project and sometimes participate in secondary, more in-depth scientific tasks. Their feedback on new projects under development guides researcher and developer efforts to improve Zooniverse.

By providing the public with a role in the scientific process, Zooniverse puts the power of science in your hands. The platform also gives volunteers a firsthand look at how science progresses from raw data to real results. “We’re very much focused on engaging people in the process of scientific discovery,” says Michelle Larson, president and CEO of the Adler Planetarium. “We learn about science in a formal setting in so much of our lives, and don’t have a full appreciation of the mystery and discovery. Zooniverse is very well aligned with that focus. We want you doing the discovery,” she stresses.

Each Zooniverse project provides a primer that explains the project’s goal and task. The development team is constantly improving the site to provide volunteers with the information they need in a simple, fun, and straightforward way. “We strive to never waste the volunteers’ time,” says Laura Trouille, Zooniverse co-investigator and director of citizen science at the Adler Planetarium.

This sentiment is echoed by the entire web development team, which seeks feedback through Zooniverse’s Talk feature (a project-specific online discussion board) and is constantly working to adapt the specific needs of each new project into code and tools for use throughout the platform. That feedback comes not only from the volunteers, but also the research teams running the projects. Facilitating an open line of communication between the two has allowed Zooniverse to grow and evolve into a worthwhile, engaging, and versatile citizen science tool.

The online discussion boards keep the volunteers around, Trouille believes. Every project has one, she says, and about 40 percent of volunteers go there to interact with each other and the researchers running the project. This extra layer of engagement allows for greater collaboration and, ultimately, discovery, Trouille explains.

“When a researcher says, ‘I want to do a Zooniverse project,’ they commit to being active on the discussion board,” she says. “They commit to providing blog posts, giving updates on their research, about who they are, what the broader research context is. The key to an engaged volunteer community and enabling the scientific discoveries is really the interaction on the discussion boards.”

“We have this amazing opportunity, with 1.6 million people around the world who’ve registered to participate in Zooniverse, to help in the process of learning about science, learning about the nature of science, learning how science works,” says Trouille. The ability to contact a researcher directly is “sort of lifting the veil on who researchers are, that they’re just people.”

And Zooniverse is designed so researchers can “grow in their communication skills through engaging with volunteers” as well, Trouille says. It provides professional researchers the opportunity to create citizen science projects within their comfort zone, allowing them to promote their research via targeted communication and receive feedback directly from volunteers during the development and testing stage.

“I think we can get a bit lost in the idea of academia being for academics,” says Samantha Blickhan, a postdoctoral fellow at the Adler Planetarium. “Zooniverse does a really great job of showing the academic community that you can involve the public in your work.”

Building a zoo

The diversity of Zooniverse is, in part, a reflection of the diversity of the web development team working behind the scenes. “There’s such an interesting mix of people who get attracted to work in Zooniverse,” says Trouille. “They’re all really drawn to the mission. They have these interesting backgrounds, and what they bring to the user experience is really reflective of their personalities.”

From the design of the Zooniverse.org homepage to the instructional pop-ups that appear as users progress, those developers are constantly working to facilitate better research and an improved user experience on both ends. They keep track of which interactive feedback is best and what keeps volunteers willing to stay and contribute. For example, “We have a lot of camera traps throughout the Serengeti, and we found that if we removed all the images where the wind moved a branch or something, with no animals in sight, users actually classified fewer images,” says Amy Boyer, another member of Adler’s team of Zooniverse web developers. It’s the thrill of discovery that keeps volunteers engaged, and that thrill is what the developers seek to maintain from project to project, all while keeping the value of volunteers’ time and effort in mind.

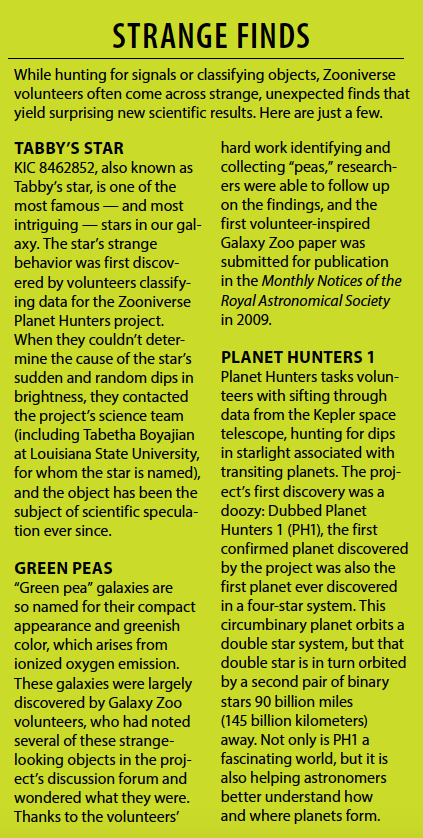

One of the biggest steps forward for the Zooniverse in recent years was the release of its free project builder tool, which was funded by a Google Global Impact Award and a Sloan Foundation grant. Launched in July 2015, this tool puts the power to create effective crowdsourced research directly in researchers’ hands. Before its release, it would take the web development team a year to build about five projects, Trouille says. That number jumped to 26 in 2016 and 40 in 2017.

New projects that want promotion via Zooniverse still undergo a rigorous beta testing phase, but the tool is available to anyone regardless of whether they want an association with Zooniverse or not. And all of Zooniverse’s code is open source, available for researchers and volunteers alike to view and, if so inclined, improve.

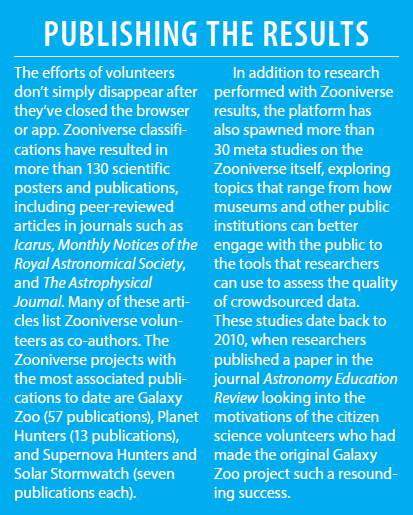

In 2017, Zooniverse celebrated its 10th anniversary with the launch of its 100th project: Galaxy Nurseries. By identifying emission lines associated with particular elements in a given galaxy, one can estimate its distance based on the amount its light is shifted due to the expansion of the universe. With accurate distances, astronomers can single out faraway “baby galaxies” to study the universe when it was much younger.

Galaxy Nurseries has now reached its goal, ending with more than 400,000 classifications and over 27,000 subjects. It is the latest in a long line of engaging projects made possible by the Zooniverse platform and its project builder tool.

Furthermore, “we have some pretty exciting results that suggest that humans and computers working together can actually produce better results than either one alone,” says Boyer. In addition to the scientific papers that come out of projects, she says, several “meta research” papers examine the process of citizen science itself.

“Zooniverse continues to push itself as well,” says Larson. “The Gravity Spy project has a machine learning component to it. Humans are doing the work that computers can’t … and then feeding their knowledge back to the computer, which moves the programming forward, and the process begins again. That’s the magic of Zooniverse, that it’s about scientific progress.”

That magic has seen the platform through a decade of success. “Galaxy Zoo was not supposed to still be running 10 years later,” says Lintott. Yet it is, and it has successfully spawned a wealth of private and public projects that have carried science into a new era of big data and bigger discoveries.

It wouldn’t be possible without the millions of registered Zooniverse users donating time and sharing excitement as part of the modern scientific process. Are you one of them?

Are you ready to get started? Here are a few of the currently active Zooniverse astronomy projects that need volunteers like you to classify real data and contribute to new scientific discoveries.

Space Warps

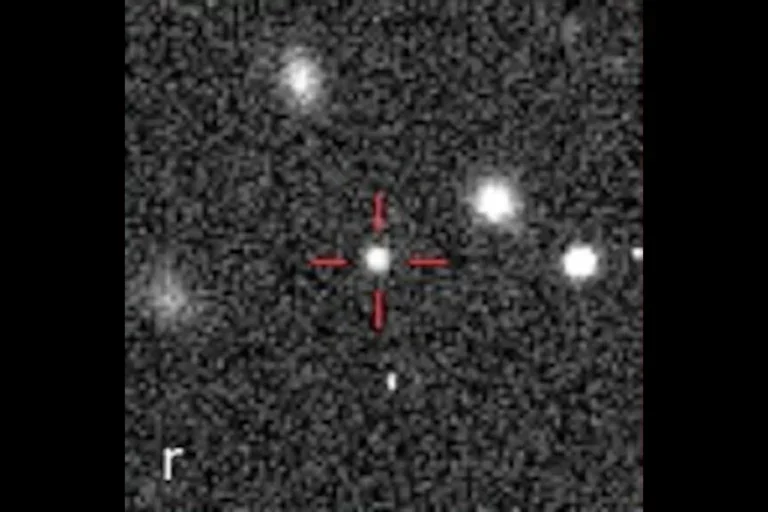

This project searches for gravitational lenses in data from the Hyper Suprime-Cam Survey, which is ideal for identifying previously unknown lenses that offer a peek into the distant universe. The project’s science team estimates there may be hundreds of previously unknown lenses in images from this survey, just waiting for volunteers like you to find them.

(spacewarps.org)

Galaxy Zoo

In the latest version of the project that started it all, Galaxy Zoo lets volunteers loose on images from the Dark Energy Camera Legacy Survey. This data set is 10 times more sensitive than the Sloan Digital Sky Survey used in the initial Galaxy Zoo project. You’ll be asked to note each galaxy’s shape, as well as any strange features such as tidal tails, dust lanes, gravitational lensing, or overlapping objects.

(galaxyzoo.org)

Gravity Spy

Want to join the hunt for gravitational waves? Gravity Spy needs volunteers to characterize glitches and false signals in the extremely sensitive instruments used to detect gravitational wave events. These glitches then can be used to teach algorithms how to filter out false signals — and identify real ones.

(gravityspy.org)

Backyard Worlds

What lurks in our own backyard? The outer solar system still hides many objects, and Backyard Worlds aims to uncover them in data from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer mission. From the theorized Planet Nine to brown dwarfs and other low-mass stars, you could discover a celestial neighbor we never knew we had. (backyardworlds.org)

Supernova Hunters

Identifying supernovae — bright stellar explosions — helps astronomers better understand the life cycles of stars, as well as map out the universe around us. Supernova Hunters invites volunteers to examine data from the Pan-STARRS1 Telescope to catch these bright but transient (and thus easily missed) events.

(www.zooniverse.org/projects/dwright04/supernova-hunters)

Galaxy Builder

Have you ever wanted to build a galaxy? If the answer is yes, then you should check out Galaxy Builder, a project that lets you assemble galaxies piece by piece to help astronomers better model these immense systems and determine how their past shapes their present.

(www.zooniverse.org/projects/tingard/galaxy-builder)

Disk detective

The Disk Detective project puts you at the forefront of planet formation studies by asking volunteers to identify young stars surrounded by the dusty, gas-filled debris disks that birth planets, comets, and asteroids. You’ll click through images taken by NASA’s Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer, which has mapped the entire sky at infrared wavelengths — the perfect regime in which to search for young, forming planetary systems. (diskdetective.org)

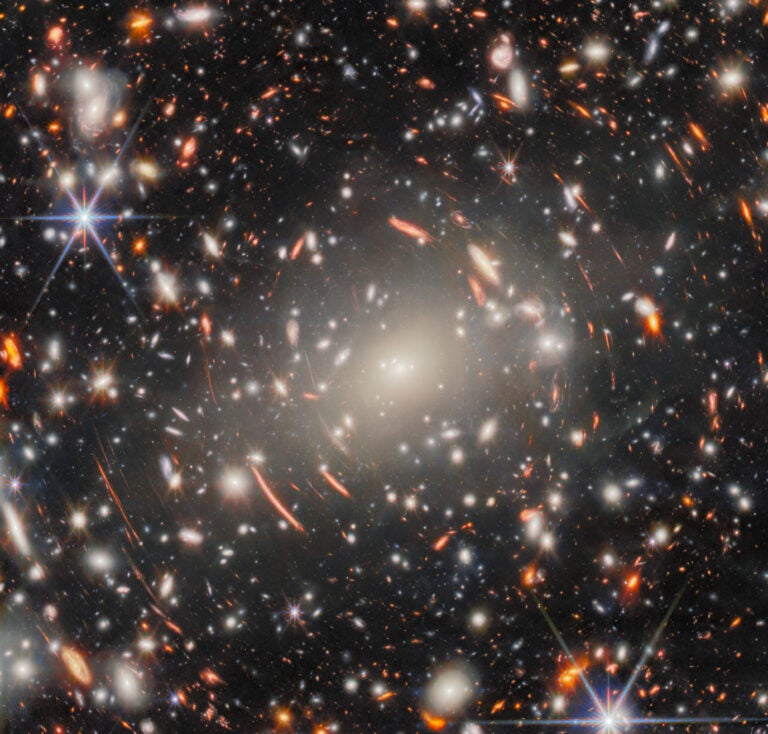

Planet Four: Terrains

Closer to home, Planet Four: Terrains focuses on the Red Planet with images taken with the Context Camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. You’ll be asked to identify terrain types in Mars’ south polar regions such as “spiders,” “channel networks,” and “swiss cheese” to help researchers discern impact craters from natural terrain. (www.zooniverse.org/projects/mschwamb/planet-four-terrain)