Key Takeaways:

Who knows what evil lurks in the heart of our galaxy? The Spitzer Space Telescope knows! The February issue of Astronomy highlighted some recent discoveries by the Galactic Legacy Midplane Survey Extraordinaire (GLIMPSE), a project conducted with the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Thanks to the reduced effects of dust obscuration in the infrared, Spitzer has discovered hundreds of previously unknown objects. These include dozens of new planetary nebulae, previously unnoticed star-forming regions, a new globular cluster, infrared bowshocks formed by winds from massive stars, outflows of molecular gas from newly forming individual stars, and other spiral galaxies seen right through the galaxy’s dusty midplane.

Enjoy these additional infrared images from the Spitzer Space Telescope.

IC 1396

This NASA Spitzer Space Telescope image of a glowing stellar nursery provides a spectacular contrast to the opaque cloud seen in visible light. The Elephant’s Trunk Nebula is an elongated dark globule within emission nebula IC 1396 in Cepheus. Located 2,450 light-years away, the region is a condensation of dense gas barely surviving the strong ionizing radiation from a nearby massive star.

This NASA Spitzer Space Telescope image of a glowing stellar nursery provides a spectacular contrast to the opaque cloud seen in visible light. The Elephant’s Trunk Nebula is an elongated dark globule within emission nebula IC 1396 in Cepheus. Located 2,450 light-years away, the region is a condensation of dense gas barely surviving the strong ionizing radiation from a nearby massive star.

Spitzer captured the spidery filaments and newborn stars of the Tarantula Nebula, a rich star-forming region also known as 30 Doradus located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, the nearest galaxy to our own Milky Way. At the nebula’s heart lies a compact cluster of stars known as R136, which contains very massive and young stars. The brightest of these blue supergiant stars are up to 100 times more massive than the Sun and at least 100,000 times more luminous.

Spitzer Space Telescope

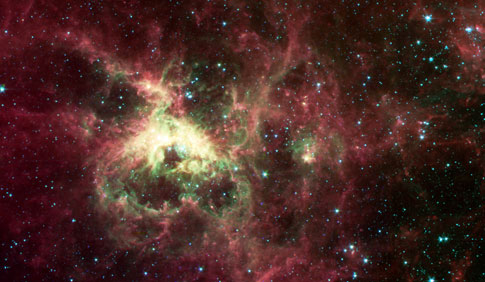

Tarantula Nebula

Spitzer captured the spidery filaments and newborn stars of the Tarantula Nebula, a rich star-forming region also known as 30 Doradus located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, the nearest galaxy to our own Milky Way. At the nebula’s heart lies a compact cluster of stars known as R136, which contains very massive and young stars. The brightest of these blue supergiant stars are up to 100 times more massive than the Sun and at least 100,000 times more luminous.

Spitzer captured the spidery filaments and newborn stars of the Tarantula Nebula, a rich star-forming region also known as 30 Doradus located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, the nearest galaxy to our own Milky Way. At the nebula’s heart lies a compact cluster of stars known as R136, which contains very massive and young stars. The brightest of these blue supergiant stars are up to 100 times more massive than the Sun and at least 100,000 times more luminous.

Spitzer captured this cluster of newborn stars buried in a rosebud-shaped (and rose-colored) nebulosity known as NGC 7129. The cluster and its associated nebula lie 3,300 light-years away in Cepheus. The stars formed from a massive cloud of gas and dust that contains enough raw material to create 1,000 Sun-like stars.

Spitzer Space Telescope

NGC 7129

Spitzer captured this cluster of newborn stars buried in a rosebud-shaped (and rose-colored) nebulosity known as NGC 7129. The cluster and its associated nebula lie 3,300 light-years away in Cepheus. The stars formed from a massive cloud of gas and dust that contains enough raw material to create 1,000 Sun-like stars.

Spitzer captured this cluster of newborn stars buried in a rosebud-shaped (and rose-colored) nebulosity known as NGC 7129. The cluster and its associated nebula lie 3,300 light-years away in Cepheus. The stars formed from a massive cloud of gas and dust that contains enough raw material to create 1,000 Sun-like stars.

Within the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) lies a star-forming region heavily obscured by interstellar dust. Spitzer used its infrared eyes to poke through the cosmic veil. It revealed a striking nebula where the entire life cycle of stars is seen in splendid detail. Astronomers are particularly interested in the LMC because its fractional content of metals (elements other than hydrogen and helium) is 2 to 5 times lower than what is seen in our solar neighborhood. As such, the LMC provides a nearby cosmic laboratory that may resemble the distant universe in its chemical composition.

Spitzer Space Telescope

Large Magellanic Cloud

Within the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) lies a star-forming region heavily obscured by interstellar dust. Spitzer used its infrared eyes to poke through the cosmic veil. It revealed a striking nebula where the entire life cycle of stars is seen in splendid detail. Astronomers are particularly interested in the LMC because its fractional content of metals (elements other than hydrogen and helium) is 2 to 5 times lower than what is seen in our solar neighborhood. As such, the LMC provides a nearby cosmic laboratory that may resemble the distant universe in its chemical composition.

Within the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) lies a star-forming region heavily obscured by interstellar dust. Spitzer used its infrared eyes to poke through the cosmic veil. It revealed a striking nebula where the entire life cycle of stars is seen in splendid detail. Astronomers are particularly interested in the LMC because its fractional content of metals (elements other than hydrogen and helium) is 2 to 5 times lower than what is seen in our solar neighborhood. As such, the LMC provides a nearby cosmic laboratory that may resemble the distant universe in its chemical composition.

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in Cygnus is a stellar nursery called DR21, which is giving birth to some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Visible-light images reveal no trace of this interstellar cauldron because of heavy dust obscuration. New images from Spitzer allow us to pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. The colorful image (top panel) is a large-scale composite mosaic assembled from data collected at different wavelengths. Views at visible wavelengths appear blue, near-infrared light is depicted as green, and mid-infrared data from the InfraRed Array Camera aboard Spitzer is red. The constituent images lie below the large mosaic.

Spitzer Space Telescope

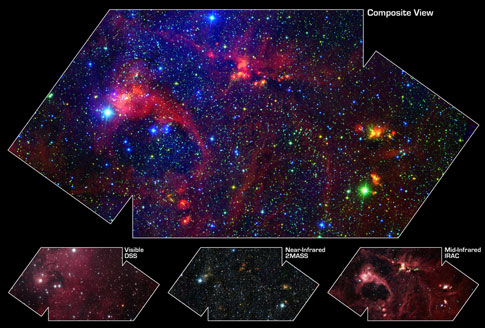

DR21

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in Cygnus is a stellar nursery called DR21, which is giving birth to some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Visible-light images reveal no trace of this interstellar cauldron because of heavy dust obscuration. New images from Spitzer allow us to pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. The colorful image (top panel) is a large-scale composite mosaic assembled from data collected at different wavelengths. Views at visible wavelengths appear blue, near-infrared light is depicted as green, and mid-infrared data from the InfraRed Array Camera aboard Spitzer is red. The constituent images lie below the large mosaic.

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in Cygnus is a stellar nursery called DR21, which is giving birth to some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Visible-light images reveal no trace of this interstellar cauldron because of heavy dust obscuration. New images from Spitzer allow us to pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. The colorful image (top panel) is a large-scale composite mosaic assembled from data collected at different wavelengths. Views at visible wavelengths appear blue, near-infrared light is depicted as green, and mid-infrared data from the InfraRed Array Camera aboard Spitzer is red. The constituent images lie below the large mosaic.

Spitzer discovered one of the most prolific birthing grounds in our Milky Way, a nebula called RCW 49. Located 13,700 light-years away in Centaurus, RCW 49 is a dark and dusty stellar nursery that houses more than 2,200 stars. Because many stars in RCW 49 are deeply embedded in plumes of dust, they cannot be seen at visible wavelengths. When viewed with Spitzer’s infrared eyes, however, RCW 49 becomes transparent.

Spitzer Space Telescope

RCW 49

Spitzer discovered one of the most prolific birthing grounds in our Milky Way, a nebula called RCW 49. Located 13,700 light-years away in Centaurus, RCW 49 is a dark and dusty stellar nursery that houses more than 2,200 stars. Because many stars in RCW 49 are deeply embedded in plumes of dust, they cannot be seen at visible wavelengths. When viewed with Spitzer’s infrared eyes, however, RCW 49 becomes transparent.

Spitzer discovered one of the most prolific birthing grounds in our Milky Way, a nebula called RCW 49. Located 13,700 light-years away in Centaurus, RCW 49 is a dark and dusty stellar nursery that houses more than 2,200 stars. Because many stars in RCW 49 are deeply embedded in plumes of dust, they cannot be seen at visible wavelengths. When viewed with Spitzer’s infrared eyes, however, RCW 49 becomes transparent.

Spitzer captured these infrared images of the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) and revealed strange structures bridging the gaps between the dust-rich spiral arms. It also traced the dust, gas and stellar populations in both the bright spiral galaxy and its companion. The visible-light image comes from Kitt Peak National Observatory’s 2.1-meter telescope, and it has the same orientation and size as the Spitzer infrared image. The light in the images originates from different sources. At shorter wavelengths, the light comes mainly from stars. This starlight fades at longer wavelengths, where we see the glow from clouds of interstellar dust. Particularly puzzling are the large number of thin filaments of red emission seen in the infrared data between the arms of the large spiral galaxy.

Spitzer Space Telescope

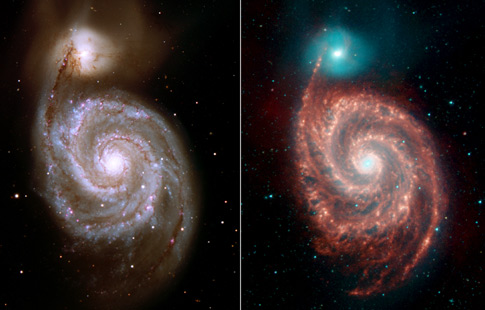

Whirlpool Galaxy

Spitzer captured these infrared images of the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) and revealed strange structures bridging the gaps between the dust-rich spiral arms. It also traced the dust, gas and stellar populations in both the bright spiral galaxy and its companion. The visible-light image comes from Kitt Peak National Observatory’s 2.1-meter telescope, and it has the same orientation and size as the Spitzer infrared image. The light in the images originates from different sources. At shorter wavelengths, the light comes mainly from stars. This starlight fades at longer wavelengths, where we see the glow from clouds of interstellar dust. Particularly puzzling are the large number of thin filaments of red emission seen in the infrared data between the arms of the large spiral galaxy.

Spitzer captured these infrared images of the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) and revealed strange structures bridging the gaps between the dust-rich spiral arms. It also traced the dust, gas and stellar populations in both the bright spiral galaxy and its companion. The visible-light image comes from Kitt Peak National Observatory’s 2.1-meter telescope, and it has the same orientation and size as the Spitzer infrared image. The light in the images originates from different sources. At shorter wavelengths, the light comes mainly from stars. This starlight fades at longer wavelengths, where we see the glow from clouds of interstellar dust. Particularly puzzling are the large number of thin filaments of red emission seen in the infrared data between the arms of the large spiral galaxy.

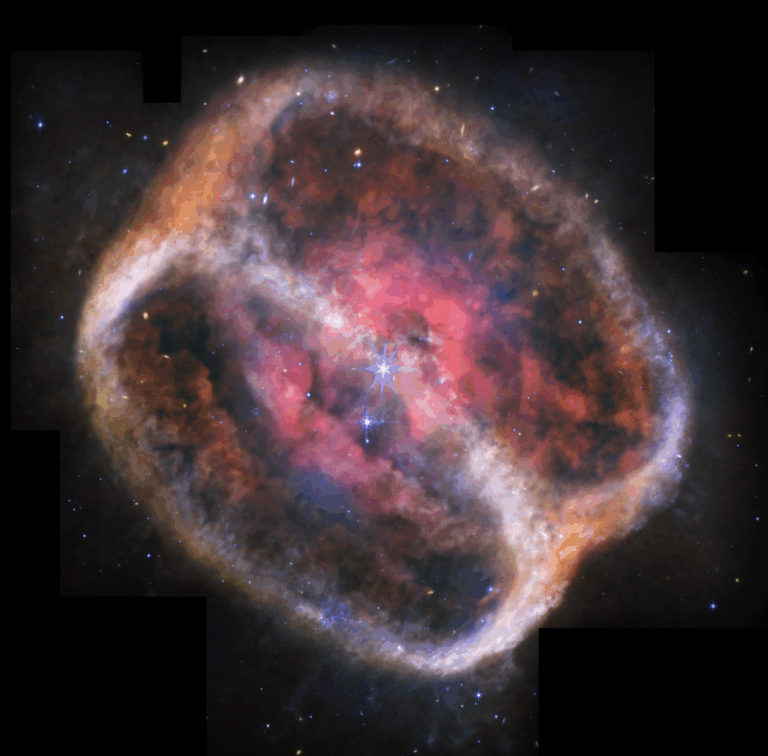

Spitzer found a delicate flower in the Ring Nebula (M57). The outer shell of this planetary nebula looks surprisingly similar to the delicate petals of a camellia blossom. A planetary nebula is a shell of material ejected from a dying star. Located about 2,000 light-years from Earth in Lyra, the Ring Nebula is one of the best examples of a planetary nebula and a favorite target of amateur astronomers.

Spitzer Space Telescope

Ring Nebula

Spitzer found a delicate flower in the Ring Nebula (M57). The outer shell of this planetary nebula looks surprisingly similar to the delicate petals of a camellia blossom. A planetary nebula is a shell of material ejected from a dying star. Located about 2,000 light-years from Earth in Lyra, the Ring Nebula is one of the best examples of a planetary nebula and a favorite target of amateur astronomers.

Spitzer found a delicate flower in the Ring Nebula (M57). The outer shell of this planetary nebula looks surprisingly similar to the delicate petals of a camellia blossom. A planetary nebula is a shell of material ejected from a dying star. Located about 2,000 light-years from Earth in Lyra, the Ring Nebula is one of the best examples of a planetary nebula and a favorite target of amateur astronomers.

This false-color Spitzer image shows the “South Pillar” area of the star-forming region called the Carina Nebula. Like cracking open a watermelon and finding its seeds, the infrared telescope revealed star embryos (yellow or white) tucked inside finger-like pillars of thick dust (pink). Hot gases are green and foreground stars are blue. Although the nebula’s most famous and massive star, Eta Carinae, is too bright to be observed by infrared telescopes, the downward-streaming rays hint at its presence above the picture frame. The inset visible-light picture of the Carina Nebula shows quite a different view. Dust pillars are fewer and appear dark because the dust is soaking up visible light. Spitzer’s infrared detectors cut through this dust, allowing it to see the heat from warm, embedded star embryos, as well as pillars buried deeper.

Spitzer Space Telescope

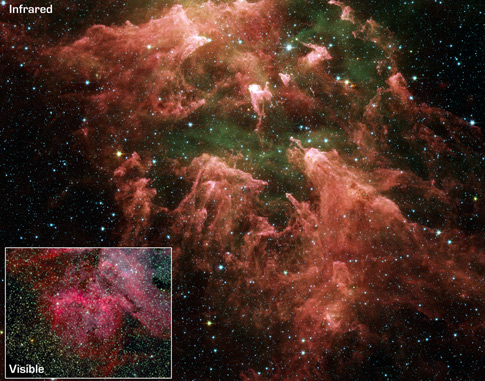

Carina Nebula

This false-color Spitzer image shows the “South Pillar” area of the star-forming region called the Carina Nebula. Like cracking open a watermelon and finding its seeds, the infrared telescope revealed star embryos (yellow or white) tucked inside finger-like pillars of thick dust (pink). Hot gases are green and foreground stars are blue. Although the nebula’s most famous and massive star, Eta Carinae, is too bright to be observed by infrared telescopes, the downward-streaming rays hint at its presence above the picture frame. The inset visible-light picture of the Carina Nebula shows quite a different view. Dust pillars are fewer and appear dark because the dust is soaking up visible light. Spitzer’s infrared detectors cut through this dust, allowing it to see the heat from warm, embedded star embryos, as well as pillars buried deeper.

This false-color Spitzer image shows the “South Pillar” area of the star-forming region called the Carina Nebula. Like cracking open a watermelon and finding its seeds, the infrared telescope revealed star embryos (yellow or white) tucked inside finger-like pillars of thick dust (pink). Hot gases are green and foreground stars are blue. Although the nebula’s most famous and massive star, Eta Carinae, is too bright to be observed by infrared telescopes, the downward-streaming rays hint at its presence above the picture frame. The inset visible-light picture of the Carina Nebula shows quite a different view. Dust pillars are fewer and appear dark because the dust is soaking up visible light. Spitzer’s infrared detectors cut through this dust, allowing it to see the heat from warm, embedded star embryos, as well as pillars buried deeper.

Located 1,000 light-years from Earth in Perseus, reflection nebula NGC 1333 epitomizes the beautiful chaos of a dense group of stars being born. Most of the visible light from the young stars in this region is obscured by the dense, dusty cloud in which they formed. With Spitzer, scientists can detect the infrared light from these objects. This allows a look through the dust to gain a more detailed understanding of how stars like our Sun begin their lives. The young stars in NGC 1333 do not form a single cluster but are split between two sub-groups. One group is to the north near the nebula shown as red in the image. The other group is south, where the features shown in yellow and green abound in the densest part of the natal gas cloud. The knotty yellow-green features in the lower portion of the image are glowing shock fronts where jets of material, spewed from extremely young embryonic stars, are plowing into the cold, dense gas nearby.

Spitzer Space Telecope

NGC 1333

Located 1,000 light-years from Earth in Perseus, reflection nebula NGC 1333 epitomizes the beautiful chaos of a dense group of stars being born. Most of the visible light from the young stars in this region is obscured by the dense, dusty cloud in which they formed. With Spitzer, scientists can detect the infrared light from these objects. This allows a look through the dust to gain a more detailed understanding of how stars like our Sun begin their lives. The young stars in NGC 1333 do not form a single cluster but are split between two sub-groups. One group is to the north near the nebula shown as red in the image. The other group is south, where the features shown in yellow and green abound in the densest part of the natal gas cloud. The knotty yellow-green features in the lower portion of the image are glowing shock fronts where jets of material, spewed from extremely young embryonic stars, are plowing into the cold, dense gas nearby.

Located 1,000 light-years from Earth in Perseus, reflection nebula NGC 1333 epitomizes the beautiful chaos of a dense group of stars being born. Most of the visible light from the young stars in this region is obscured by the dense, dusty cloud in which they formed. With Spitzer, scientists can detect the infrared light from these objects. This allows a look through the dust to gain a more detailed understanding of how stars like our Sun begin their lives. The young stars in NGC 1333 do not form a single cluster but are split between two sub-groups. One group is to the north near the nebula shown as red in the image. The other group is south, where the features shown in yellow and green abound in the densest part of the natal gas cloud. The knotty yellow-green features in the lower portion of the image are glowing shock fronts where jets of material, spewed from extremely young embryonic stars, are plowing into the cold, dense gas nearby.

This dazzling infrared image from Spitzer shows hundreds of thousands of stars crowded into the Milky Way’s swirling core. In visible-light pictures, this region cannot be seen at all because dust lying between Earth and the galactic center blocks our view. In this false-color picture, old and cool stars are blue, while dust features, lit up by blazing hot, massive stars, are reddish. Both bright and dark filamentary clouds show up, and many of them harbor stellar nurseries. The plane of the Milky Way’s flat disk is apparent as the main, horizontal band of clouds. The brightest white spot in the middle is the center of the galaxy, which also marks the site of a supermassive black hole.

Spitzer Space Telescope

Milky Way’s swirling core

This dazzling infrared image from Spitzer shows hundreds of thousands of stars crowded into the Milky Way’s swirling core. In visible-light pictures, this region cannot be seen at all because dust lying between Earth and the galactic center blocks our view. In this false-color picture, old and cool stars are blue, while dust features, lit up by blazing hot, massive stars, are reddish. Both bright and dark filamentary clouds show up, and many of them harbor stellar nurseries. The plane of the Milky Way’s flat disk is apparent as the main, horizontal band of clouds. The brightest white spot in the middle is the center of the galaxy, which also marks the site of a supermassive black hole.

This dazzling infrared image from Spitzer shows hundreds of thousands of stars crowded into the Milky Way’s swirling core. In visible-light pictures, this region cannot be seen at all because dust lying between Earth and the galactic center blocks our view. In this false-color picture, old and cool stars are blue, while dust features, lit up by blazing hot, massive stars, are reddish. Both bright and dark filamentary clouds show up, and many of them harbor stellar nurseries. The plane of the Milky Way’s flat disk is apparent as the main, horizontal band of clouds. The brightest white spot in the middle is the center of the galaxy, which also marks the site of a supermassive black hole.