Key Takeaways:

- The Andromeda constellation, encompassing the mythological princess, is notable for its size (19th largest) and moderate brightness (37th brightest), with its brightest star, Alpheratz, officially designated as part of Andromeda only since 1922.

- The article details observation of several celestial objects within Andromeda, including the barred spiral galaxy NGC 7640, the planetary nebula NGC 7662 (Blue Snowball), the open cluster NGC 7686, and the dwarf elliptical galaxies NGC 205 and M32, all with varying descriptions of their visibility and features under different telescope magnifications.

- Further observational targets described include the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Mirach's Ghost (NGC 404), the open cluster NGC 752, the double star Almach (Gamma Andromedae), the edge-on spiral galaxy NGC 891 (Silver Sliver), and the asterism NGC 956, each characterized by their magnitude, size, and observational characteristics using varied equipment.

- The article emphasizes the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) as the constellation's showpiece, visible to the naked eye and significantly large, suggesting observation methods using binoculars and telescopes at varying magnifications to appreciate its features, including its satellite galaxies and dust lanes.

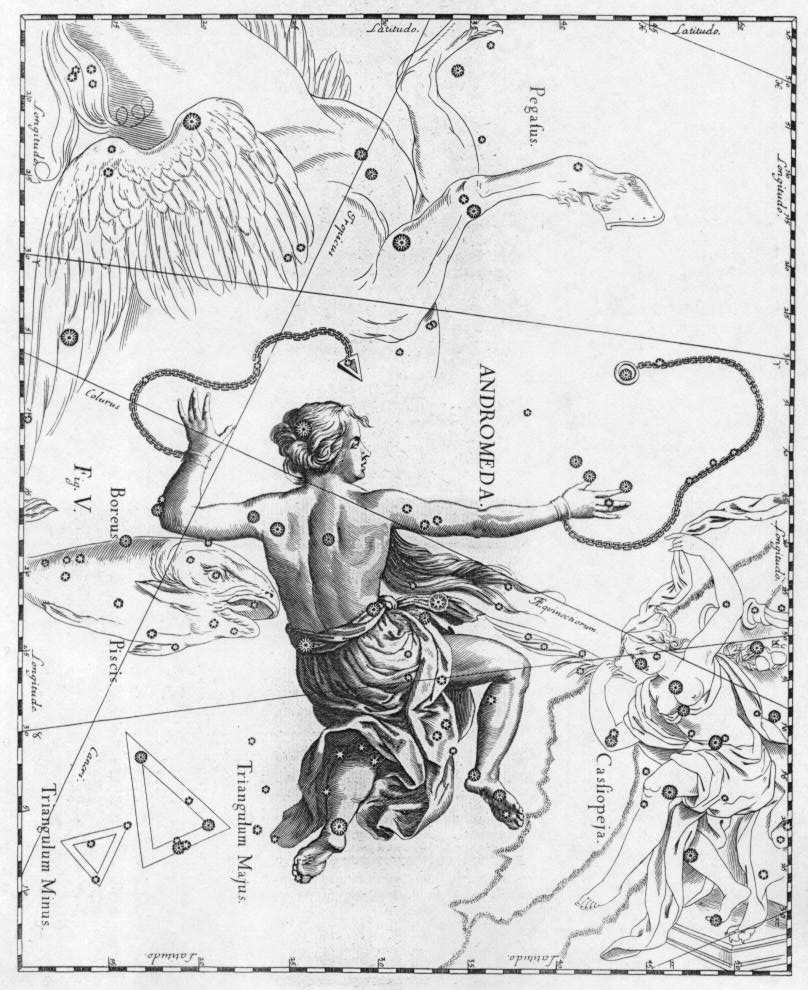

The constellation Andromeda the Princess is part of the largest mythologically connected group in the sky. Her parents are Cepheus the King and Cassiopeia the Queen. Perseus the Hero saved her from being sacrificed to Cetus the Whale (a sea monster in the tale). And Pegasus the Winged Horse was born when Perseus cut off the Gorgon Medusa’s head.

Andromeda is best viewed in the early evening during the first two weeks of October when — from our perspective — it lies across the sky from the Sun. It’s invisible around early April when it lines up with our daytime star.

The Princess is above average in size, ranking 19th among the 88 constellations, and near the middle (37th) in overall brightness. Interestingly, its brightest star, Alpheratz (Alpha [α] Andromedae), has been an official part of the figure only since 1922. Before then, it was also designated Delta (δ) Pegasi, and, indeed, it’s still the brightest of the four stars in the asterism called the Great Square of Pegasus.

As is my habit when I describe objects within a constellation, I start with the ones farthest west and move eastward so each subsequent object will rise higher as the evening progresses.

Feast your eyes

We’ll start our observing session with a bit of a tough one. It’s barred spiral galaxy NGC 7640, which glows at magnitude 11.3. As if that weren’t faint enough, it’s one of those “slender slivers” in the sky, measuring 10′ by 2.2′.

To find it, point your telescope 4° east-southeast of Omicron (ο) Andromedae. You’ll see its main features — an elongated core and two really faint arms — through an 8-inch telescope. An 11-inch scope will reveal subtle extensions to the north and south. This galaxy contains some big star-forming regions near the core, which make it look unevenly lit.

Once you’ve checked that tough catch off the list, it’s time to enjoy the Blue Snowball (NGC 7662). This planetary nebula also is number 22 in Patrick Moore’s Caldwell Catalog. It glows at magnitude 8.3 and has an oval shape that measures 12″ by 18″. Look for it not quite 2½° west-southwest of Iota (ι) Andromedae.

I’ve had fun comparing what I detect as the color of this object with other observers. Some see it as light blue, turquoise, a bit more white than blue, and differing hues of light green. The cool thing is that we’re all right, at least in our own minds, because human eyes vary slightly in their sense of color perception. Does this object warrant its common name based on your eyes?

An 8-inch scope with an eyepiece that gives a magnification of 200x or more will reveal a ring of gas around the Snowball’s hollow center. There’s a 13th-magnitude central star in there, but you’ll need a much bigger scope to spot it. Look closer and see if you can see the faint gas shell that surrounds the ring.

Next up is an open cluster that sharp-eyed observers can spot with their naked eyes from a dark observing site. It’s NGC 7686, which glows at magnitude 5.6 and measures a worthy 15′ across — half the diameter of the Full Moon.

To find it, aim your telescope 3° north-northwest of Lambda (λ) Andromedae. Some observers report that the cluster has a triangular appearance, but that depends on the magnification you’re using. Low powers show that figure best. Medium-size telescopes reveal about two dozen stars, two of which are brighter than the rest. Larger instruments will triple that number, but all of those stars are quite faint.

Now we come to NGC 205 and M32, two of the sky’s classic dwarf elliptical galaxies. They’re bright and super easy to find: Just locate the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). Any telescope will show NGC 205 and M32 as satellites of that celestial wonder.

Both galaxies glow around 8th magnitude, but NGC 205 appears three times bigger. It measures 19.5′ by 12.5′, while M32 measures “only” 11′ by 7.3′. That’s still about 11 percent of the area the Full Moon covers. Neither of these galaxies shows any details no matter what scope you point at them, so give them a quick look and let’s turn our attention to the object you’re reading this story for.

The Andromeda Galaxy is the only such object named for its constellation. Visible to the naked eye — and looking like a piece of the Milky Way that broke off — from even moderately dark sites, this object also goes by the designations M31, NGC 224, HD 3969, UGC 454, and lots more. It’s famous for many reasons, but observers value it as the showpiece celestial object of the northern sky. Indeed, with a magnitude of 3.4, only the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds are brighter than M31.

The Andromeda Galaxy is a giant. It covers 185′ by 75′. That length is roughly the same as six Full Moons side by side, and its area is greater than 18 Full Moons. Because it is so big, you can approach studying it in one of two ways.

If you have access to 15x or 20x binoculars, start by looking at the entire galaxy. First, note the true field of view of your binoculars, a number usually printed on them. Then determine how much of M31’s length you can see by counting how many fields it takes to take it all in. Second, identify M32 and NGC 205, which are right next to their big brother. Third, compare those two galaxies to M31’s nucleus, which resembles an elliptical galaxy. Finally, find the dark lanes — made primarily of dust — along the spiral arms.

The other way to observe the Andromeda Galaxy is by cranking up the power and examining small parts of it through your telescope. An 11-inch or larger scope works best. Look for several star-forming regions within M31’s spiral arms.

Next on our list is an elliptical galaxy called Mirach’s Ghost, also known as NGC 404. The common name comes from the fact that the Ghost lies a mere 7′ from Mirach (Beta [β] Andromedae), a star of magnitude 2.1. It glows at magnitude 10.1 and has a diameter of 6′. That makes Mirach 1,738 times as bright as its Ghost, and that makes NGC 404 a little tough to see.

But tough doesn’t mean impossible. In an 8-inch scope, insert an eyepiece that gives a magnification around 200x. Then just nudge the star out of the field of view. You’ll see a circular patch of light with a brighter center and — as with most ellipticals — no detail. It is, however, fun to show people this object.

Our next object, open cluster NGC 752, lies closer to Beta Trianguli (not quite 4° northwest of it) than to Beta Andromedae. Most sharp-eyed observers can spot it without optical aid from a dark site. It shines at magnitude 5.7 and spans an impressive 50′.

Because it’s so big and bright, you should be able to spot some 30 stars through 10x binoculars. Through a telescope, if you keep the magnification below 50x, that number will jump to 100. Note the zigzag line of four stars that runs east to west through the center of NGC 752.

Now we come to the only double star on our list, Almach (Gamma [γ] Andromedae), and it’s a nice one. Although it appears as a single star to our eyes, pretty much any telescope will split the pair into yellow Gamma1 (γ1), which glows at magnitude 2.3, and blue Gamma2 (γ2), which glows at magnitude 5.0. The separation between the pair is 9.8″.

Just a note that if you have access to an 11-inch or larger scope, you might try to split Gamma2, as it is a binary as well. Its two stars are much closer — a mere 0.4″ apart, and their magnitudes are nearly identical: 5.1 and 6.3.

Next up is one of my favorite galaxies, but I’m partial to edge-on spirals. Yes, I know M31 is technically edge-on, but the Silver Sliver (NGC 891), also known as Caldwell 23, inclines a mere 1.4° to our line of sight. To find it, start at Almach and head 3½° east.

The Sliver glows at magnitude 10 and got its common name because it’s four times as long as it is wide, measuring 13′ by 2.8′. Because it is so slender, it looks best through 11-inch and larger telescopes.

At low power, the field of view contains dozens of Milky Way stars that lie a lot closer to us than to NGC 891. The galaxy’s slight central bulge is also evident at low powers, but you’ll want to crank the magnification past 200x to examine the dust lane that divides the galaxy lengthwise into two parts.

Our final object is NGC 956, which was originally classified as an open cluster, but astronomers now consider an asterism — a chance alignment of stars. In fact, the two brightest stars in the cluster, which lie at its northern and southern edges, are much closer to us than the rest of the ones we can see. NGC 956 lies 5.7° east-northeast of Almach. It glows at magnitude 8.9 and has a diameter of 6′.

As you can see, Andromeda has a lot more going for it than just its namesake galaxy. Head out one night soon and enjoy its wonders. Good luck!