Key Takeaways:

A study pokes holes in the current understanding of galaxy formation and questions the accepted model of the origin and evolution of the universe. According to the standard paradigm, 23 percent of the mass of the universe is shaped by invisible particles known as dark matter.

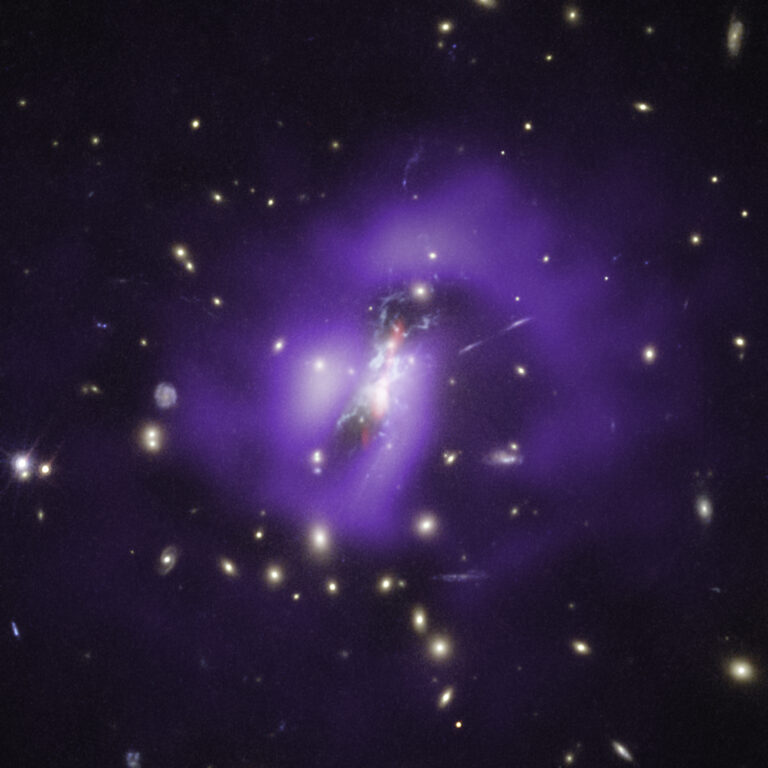

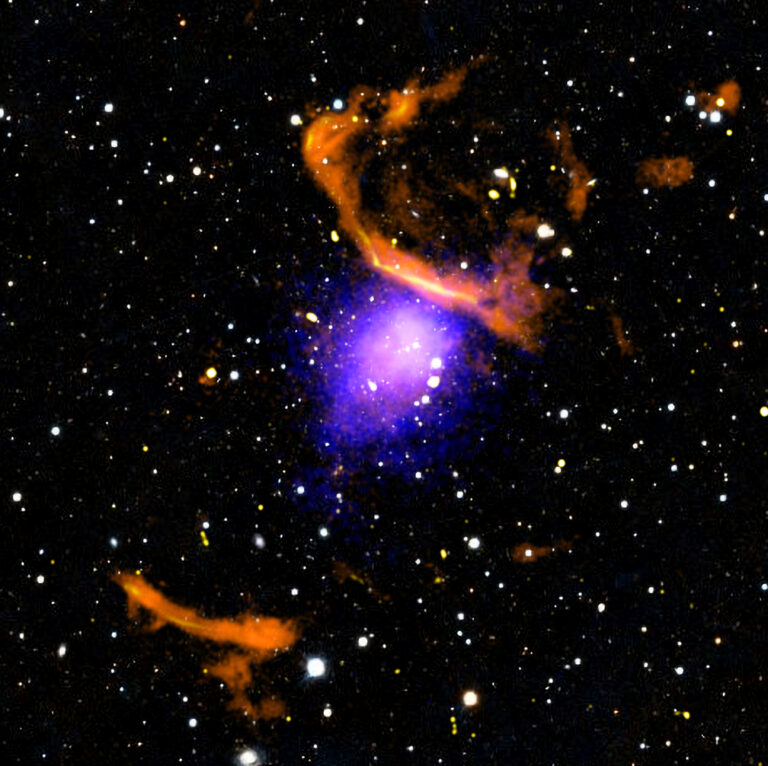

“The model predicts that dwarf galaxies should form inside of small clumps of dark matter and that these clumps should be distributed randomly about their parent galaxy,” said David Merritt from the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. “But what is observed is very different. The dwarf galaxies belonging to the Milky Way and Andromeda are seen to be orbiting in huge, thin disk-like structures.”

The study, led by Marcel Pawlowski at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, critiques three recent papers by different international teams, all of which concluded that the satellite galaxies support the standard model. The critique by Merritt and his colleagues found serious issues with all three studies.

The team of 14 scientists from six different countries replicated the earlier analyses using the same data and cosmological simulations and came up with much lower probabilities — roughly one-tenth of a percent — that such structures would be seen in the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies.

“The earlier papers found structures in the simulations that no one would say really looked very much like the observed planar structures,” said Merritt.

In their paper, Merritt and his co-authors write that, “Either the selection of model satellites is different from that of the observed ones, or an incomplete set of observational constraints has been considered, or the observed satellite distribution is inconsistent with basic assumptions. Once these issues have been addressed, the conclusions are different: Features like the observed planar structures are very rare.”

The standard cosmological model is the frame of reference for many generations of scientists, some of whom are beginning to question its ability to accurately reproduce what is observed in the nearby universe. Merritt counts himself among the small and growing group that is questioning the accepted paradigm.

“Our conclusion tends to favor an alternate and much older model: that the satellites were pulled out from another galaxy when it interacted with the Local Group galaxies in the distant past,” he said. “This ‘tidal’ model can naturally explain why the observed satellites are orbiting in thin disks.”

Scientific progress embraces challenges to upheld theories and models for a reason, Merritt notes.

“When you have a clear contradiction like this, you ought to focus on it,” Merritt said. “This is how progress in science is made.”