Of course, it’s had many names across many cultures, some of which still linger. The study of the Moon is selenology, thanks to the Greek goddess Selene; her Roman counterpart was Luna. In China, the Moon goddess was Chang’e, a name now bestowed upon the Chinese space agency’s lunar missions.

It’s only thanks to such exploration that we’ve learned what we know about the Moon.

The Moon’s history is a violent one, starting with its birth when a Mars-sized object — dubbed Theia — smashed into the young Earth billions of years ago. The resulting debris eventually coalesced to form our satellite. This origin story arose because lunar rock samples are molecularly pretty similar to samples from Earth, implying the Moon formed out of our planet.

But the impactor theory, as it’s known, suggests the Moon should have traces of both Earth and Theia — and we’ve never spotted anything Theia-ish over there. It could be that the crash was more of a glancing blow, with the bulk of Theia leaving the vicinity.

Scientists don’t really know how to explain this aspect of the Moon’s genesis, but they do know the origins of the biggest lunar features. Over the eons, asteroids have pummeled the Moon’s surface, sometimes cracking it open to spill the molten rock within, which hardened into the dark lunar spots, called maria.

The oldest and largest impact site, the South Pole’s Aitkin Basin, covers nearly a quarter of the Moon’s far side. (Like other old features, it’s also covered with fresh craters.) The bright craters dotting the Moon’s near side, though, are the result of more recent asteroid impacts.

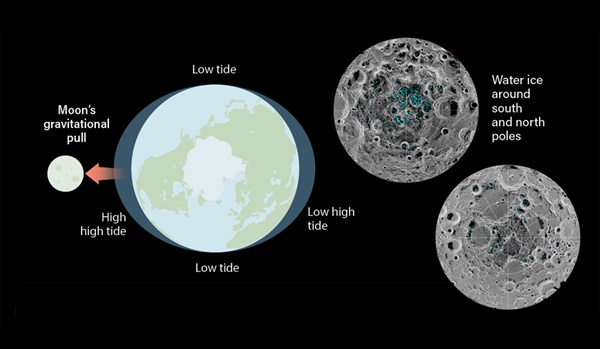

Humans have long associated oceans with the Moon, understanding from observation that, even before we knew why, the Moon influenced the tides. We now know the Moon’s gravitational pull tugs at Earth’s bodies of water.

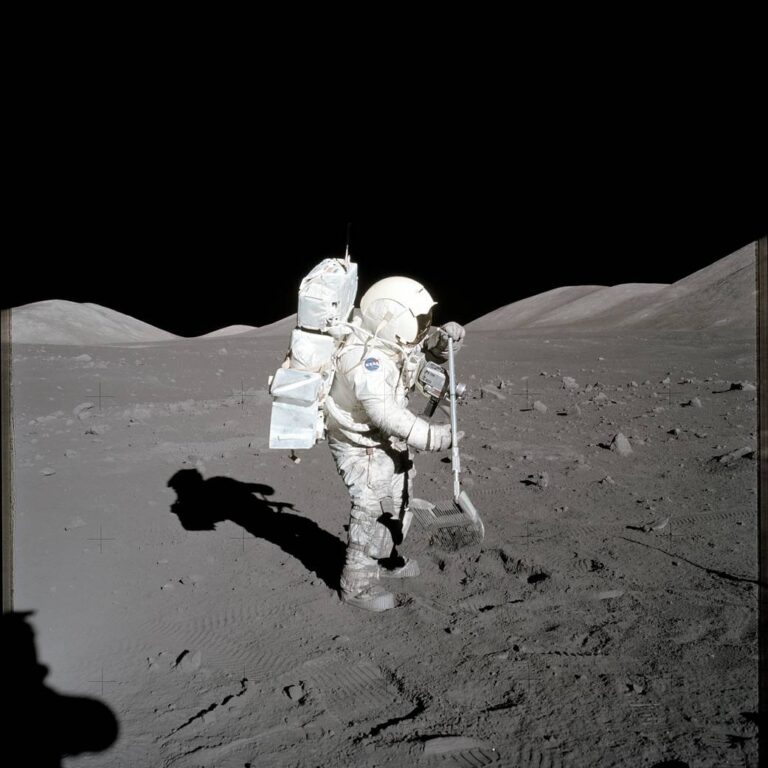

The association goes both ways, too. Scientists named the Moon’s dark areas maria — meaning “seas” in Latin — long before telescopes revealed there was no water on the lunar surface. And while the Apollo astronauts hoped to find water underground, all the soil samples they returned suggested the Moon was barren and dry.

The odds of a watery moon have since improved, however. The Indian Chandrayaan-1 mission, and then NASA’s LCROSS, hurled probes into the satellite to analyze the resulting dust cloud. Both turned up a surprising amount of water. And last year, researchers revealed what many had long suspected: Water ice could and does hide in permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles.

Such stores of water would be extremely valuable, should we ever get a Moon-orbiting space station (the closest we’re likely to come to a lunar settlement in the near future).

When the media start talking about the “super blood Moon,” people often get confused. But it’s not all sensationalism — these terms tell us something about the Moon’s current state.

Supermoon: A Full Moon when it’s physically closest to Earth, making it appear 14 percent bigger than when it’s at its smallest and farthest. Despite the hype, though, human eyes can’t actually tell the difference.

Blue Moon: Originally, this was the third Full Moon in a season that has four Full Moons. (Three is normal.) Within the past century, it has shifted to mean the second Full Moon in one calendar month. Both are rare.

Blood Moon: The part of a total lunar eclipse when the Moon enters Earth’s shadow. A partially eclipsed Moon simply looks dark, like something has taken a bite out of it. But during totality, all of Earth’s sunsets and sunrises trickle through our atmosphere to tinge the Moon’s shadowed surface.

Solar eclipse: This term doesn’t include the word Moon, but it’s when our satellite aligns between Earth and the Sun at just the right angle to cast a shadow on Earth’s surface. Like lunar eclipses, this phenomenon is possible only because the Sun and Moon appear the same size in Earth’s sky; if the Moon were closer (as it once was) or farther (as it will be), no eclipses could occur.

In the 1970s, the Nixon administration gave out plaques containing lunar samples from Apollo 11 and 17 to all 50 states and 135 other nations. Some kept good track of these gifts. Many did not. Governors and world leaders often accidentally misplaced the samples when they left office; many have been recovered from their private collections later. The hunt for the remaining samples is ongoing.

That Time We Thought About Nuking the Moon

Most people agree that the United States won the Space Race against the Soviet Union when the Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon in 1969. But America was running behind for most of the contest, and things almost ended very differently. In 1959, the Air Force presented a plan mildly titled “A Study of Lunar Research Flights” that suggested launching a nuclear weapon into the Moon — not for science, but simply as a show of strength. For the sake of both humanity and the Moon, the government didn’t pursue the plan.