Key Takeaways:

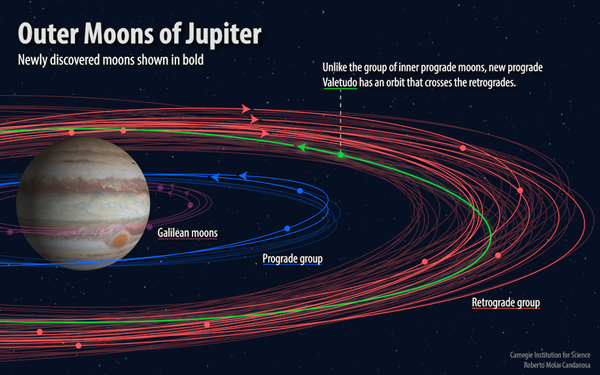

- Twelve new Jovian moons were discovered, increasing the total known count to 79. These discoveries were a serendipitous outcome of a separate Planet Nine search.

- The research utilized the Blanco 4-meter telescope, leveraging its wide field of view and stray light suppression capabilities.

- One newly discovered moon, designated Valetudo, exhibits a prograde orbit, contrasting with the retrograde orbits of other outer moons, potentially suggesting past collisions.

- The existence of these smaller moons provides evidence that their formation occurred after the gas and dust of the early solar system had dispersed.

On Tuesday, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) announced the discovery of 10 new moons orbiting Jupiter. Along with two found through the same research project but announced in June 2017, this brings the roster of Jupiter’s known natural satellites to 79.

One of these new moons turned out to be a bit of a rebel. Of the 12 latest moons to join Jupiter’s family, it’s a maverick whose odd orbit may give astronomers crucial insights to understanding how the moons of Jupiter came to be.

Two Birds with One ‘Scope

The discovery of these moons came from a totally different search for new solar system bodies. Astronomer Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science is on the hunt for Planet Nine, a hypothetical planet many astronomers think should exist in the distant reaches of our Solar System, beyond Pluto. He and his team have been photographing the skies with some of today’s best telescope technology, hoping to catch sight of this mysterious ninth planet.

In the spring of 2017, Jupiter happened to be in an area of sky the team wanted to search for Planet Nine. Sheppard, who is broadly interested in the formation of solar systems and has been involved in the discovery of 48 of Jupiter’s known moons, realized this was the perfect opportunity to advance two separate research goals with the same telescope data.

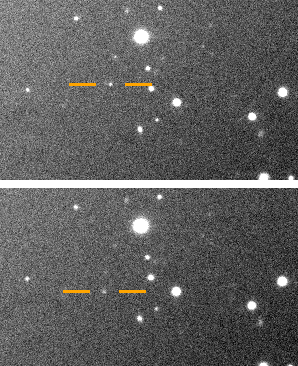

The Blanco 4-meter telescope Sheppard was using is uniquely suited to spotting potential new moons both because the camera installed on it can photograph a huge area of sky at once and because it’s particularly good at blocking stray light from bright objects nearby — say, Jupiter — that might wash out fainter ones.

“It’s allowed us to cover the whole area around Jupiter in a few shots, unlike before, and we’re able to go fainter than people have been able to go before,” says Sheppard.

Once the Blanco telescope spotted previously unidentified objects near Jupiter, the research team used other telescopes to follow up on these moon candidates and confirm that they were orbiting Jupiter.

One moon in particular caught the researchers’ attention.

“The most interesting find is this object we’re calling Valetudo,” Sheppard says. “It’s like it’s going down the highway in the wrong direction.”

Of the 79 moons now known, most orbit in the same direction as other moons nearest them. The moons closer to Jupiter, including the four Galilean satellites, orbit Jupiter in the same direction as the planet’s rotation — astronomers call this a prograde orbit. The outer moons move in the opposite direction — a retrograde orbit.

Eleven of the twelve new moons follow these conventions, but Valetudo is the odd one out. It’s out where the outer, retrograde moons are, but it’s orbiting Jupiter in the prograde direction, driving into the oncoming traffic.

The curious find might shed light on how many of Jupiter’s current moons were formed. Aside from the hulking Galilean moons that stretch thousands of miles in diameter, most of Jupiter’s moons, including the new twelve, are between a mile and a few tens of miles across. The outer moons are clustered in at least three groups based on their distances from Jupiter and the angles of their orbits, and astronomers think these moons are fragments of three larger objects that were captured by Jupiter’s gravity and later broken up by collisions — though whether that was with passing comets, rogue asteroids, or other moons is unclear.

Because Valetudo’s orbit crosses the orbits of some of the outer retrograde moons, it’s possible that it suffered a head-on collision in the past. The research team thinks Valetudo could be a leftover chunk from a once-larger moon that rammed into another past Jovian satellite, creating the many smaller objects that exist today. To check whether this could have happened, the researchers are working on supercomputer simulations of these orbits to calculate how many times an object with Valetudo’s orbit could have collided with the retrograde moons in the solar system’s lifetime.

Lunar Remnants

Finding lots of these small moons also tells us about conditions in the early solar system. When Jupiter and the other giant planets were forming, the solar system was a disk and gas and dust that surrounded the infant Sun.

“The giant planets formed out of material that used to be in that region. They were like vacuums, they sucked up all that material and that created the planets,” Sheppard explains. “We think these moons are the last remnants of the material that formed the giant planets.”

The fact that these smaller moons exist today is evidence that any collisions that created them happened after this era of planet formation. If small moons like these were around when the solar system was still thick with gas and dust, drag forces would have slowed them down and caused them to fall into Jupiter, never to be seen again. Only in today’s much emptier solar system, after the giant planets finished forming and clearing their surroundings of gas and dust, would small moons like these have been able to survive.

Once they finish running and analyzing the simulations, the team plans to publish the results in early 2019. In the meantime, they’re waiting for the IAU to formally accept “Valetudo” as the name for the oddball moon.

The IAU requires moons of Jupiter to have names related to the Roman god Jupiter. Valetudo is the name of Jupiter’s great-granddaughter and a Roman goddess of health and hygiene, so it fits the bill. But why hygiene? Sheppard says it comes from an inside joke with his girlfriend.

“I kind of always jokingly say that she’s a very cleanly person; she likes to take multiple showers a day,” Sheppard says. “And so when she told me about Valetudo, which is the goddess of hygiene, I said ‘That’s it, that’s what we’re naming it.’”

This article originally appeared on Discovermagazine.com.