The largest “depleted galaxy” ever observed apparently did not form according to the most popular model.

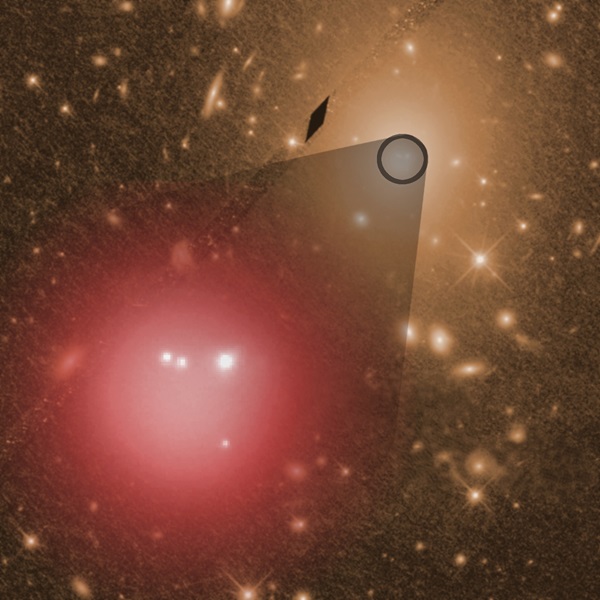

The galaxy, designated 2MASX J17222717+3207571, is remarkable for its size (a total stellar mass of 4.44 trillion solar masses) and for the stars missing from its core (175 billion solar masses). By comparison, the Milky Way tips the cosmic scale at a meager 60 billion solar masses.

Astronomers call a galactic core “depleted” when the mass density of stars in its core does not follow the progression set by the outer part of the galaxy. The density of stars in most galaxies increases smoothly from the outer edge to the center. Astronomers can plot the actual progression in a galaxy and compare it with the expected, smooth progression. In some galaxies, the actual number of stars in the central bulge falls short of what is expected.

Depleted cores show up in only a small percentage of galaxies, but they are fairly common in very large galaxies, according to Alister Graham, a professor of astronomy at Swinburne University of Technology’s Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing. “It’s only galaxies with a spheroidal distribution of stars more massive than about 200 billion solar masses. As a general rule, this excludes all spiral galaxies.”

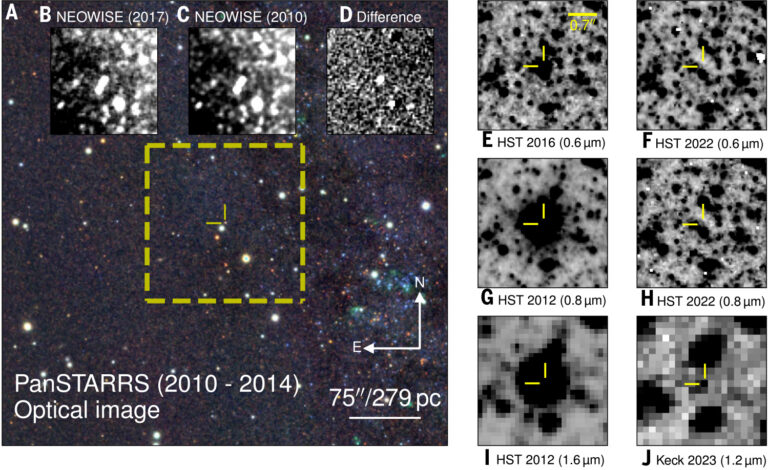

After a close inspection of what was thought to be the largest depleted galaxy core last year and finding that the initial analysis was mistaken, Graham and Paolo Bonfini, from Centro de Radioastronomía y Astrofísica in Mexico, decided to take a closer look at the next two largest depleted galaxies.

Graham and Bonfini, who was the lead author, published their results in the Sept. 23, 2016, Astrophysical Journal (Vol. 829, No. 81, “The Quest for the Largest Depleted Galaxy Core: Supermassive Black Hole Binaries And Stalled Infalling Satellites”; http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/0004-637X/829/2/81/pdf).

The smaller of the two galaxies, designated 2MASX J09194427+5622012, appears to have formed by the merger of two similar-size smaller galaxies. Each of the two merging galaxies had a supermassive black hole at its center. As the two cores merged into each other, some of the stars were flung out, the way an Earth spacecraft gains speed as it slingshots around a gas giant planet such as Jupiter.

“Some stars may be kicked right out of the galaxy,” says Graham, “while others now orbit in the middle and outer regions of the galaxy.”

Galaxy ’012 apparently formed through the “binary black hole scouring scenario,” a widely accepted model for how galaxies merge and form depleted cores.

The revelation came from the bigger depleted galaxy, which shows no evidence of containing a supermassive black hole. Galaxy ’571 has a core that is evenly distributed with stars — except for a handful of dense knots of stars near the core’s edge.

“When this model was first introduced, the cores it produced were so large, and the central mass deficits so great, that it was considered excessive,” says Graham. “Nothing so big had ever been observed. But that all changed with 2MASX J17222717+3207571 (‘571), which perfectly matches the unusually large, constant-density core seen in the simulations.”

The pair of supermassive black holes dominate the action in what astronomers call the “scouring scenario,” slinging normal stars aside as they plunge toward each other. Imagine a rock falling into a swimming pool of water.

Without the black holes, a tightly bound star core being drawn into a uniformly distributed star core is more like a chunk of chocolate sinking into a pool of warm pudding. Astronomers refer to the idea more precisely as the “stalled perturber scenario.”

The pudding metaphor has limitations, of course. For example, around the edges of the tightly bound core, individual stars exchange kinetic energy with the surrounding stars, some of which are ejected.

The core of galaxy ’571 may have started life with a typical undepleted density peak in the middle, but when it started swallowing its small satellite galaxies, its core density started to even out.

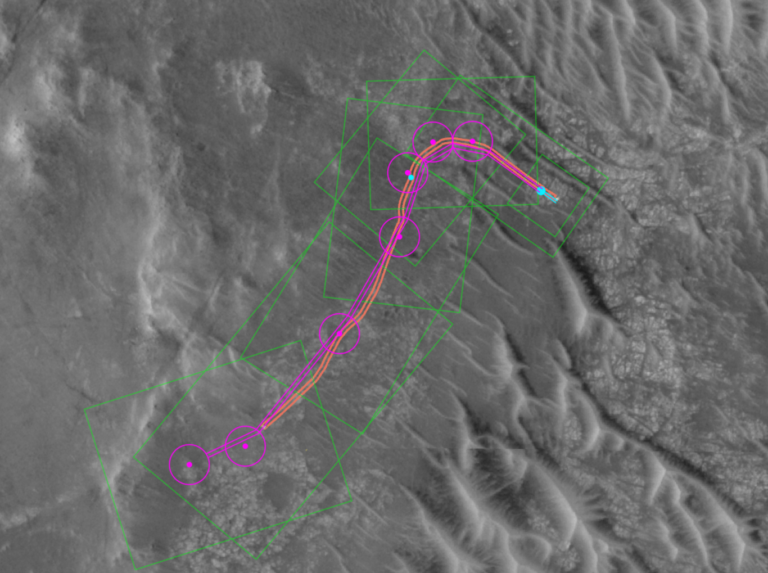

“The inner stellar density gradient in the big galaxy is eroded away as the satellites sink in,” explains Graham. “The satellites sink (their orbital energy is reduced) while the centrally located stars of the big galaxy are ejected out (their orbital energy increases). Once the core has a constant density, the satellites’ in-fall is stalled; they loiter at the boundary of this core for a very long time.”

Numerical confirmation

Graham and Bonfini ran computer simulations and found that the structure of the core of galaxy ’571 is consistent with a large galaxy with a roughly constant-density core and no supermassive black hole swallowing a much smaller galaxy with a tightly bound core but also without a supermassive black hole.

“It is hard to know exactly the history of mergers and activity for any one galaxy,” but the stalled perturber scenario remains a valid idea, according to Christopher Conselice, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Nottingham in the U.K. Conselice was not involved in Bonfini and Graham’s study. “The arguments they give are fairly solid, but the other possibilities still remain. More data is needed, and especially more simulations need to be carried out to interpret what we observe.”

Located at the center of a cluster containing hundreds of galaxies, galaxy ’571 continues to grow by swallowing the smaller galaxies around it, says Graham. The remnants of the dense cores of five of those swallowed galaxies can be seen in images of galaxy ’571. They hover near the edge of galaxy ’571’s core as monuments to their past life.

“For a couple of decades now, SMBHs [supermassive black holes] have been the go-to bad boy when people observe the damaged cores of galaxies,” says Graham. “While they are undoubtedly guilty of many of these crimes, some of the damage may have resulted from poor satellite galaxies that have been captured. I already have plans to revisit images of some 100 nearby galaxies known to have damaged cores and look for possible (previously overlooked or ignored) remnants of semidigested galaxies.”

Allen Zeyher is a freelance writer in the Chicago area.