Key Takeaways:

“We knew before that some halos existed, but, using the full power of the upgraded VLA and the full power of some advanced image-processing techniques, we found that these halos are much more common among spiral galaxies than we had realized,” said Judith Irwin of Queen’s University in Canada.

Spiral galaxies, like our Milky Way, have the vast majority of their stars, gas, and dust in a flat, rotating disk with spiral arms. Most of the light and radio waves seen with telescopes come from objects in that disk. Learning about the environment above and below such disks has been difficult.

The “Continuum Halos in Nearby Galaxies, an EVLA Survey” (CHANG-ES) project, brings together scientists from all over the globe in order to investigate the occurrence and origin of radio halos, to probe the disk-halo interface, and to study in-disk emission as well as their magnetic fields and the cosmic rays illuminating these fields. The goal is to understand connections between radio halos and the host disk and its environment.

“Studying these halos with radio telescopes can give us valuable information about a wide range of phenomena, including the rate of star formation within the disk, the winds from exploding stars, and the nature and origin of the galaxies’ magnetic fields,” said Theresa Wiegert from Queen’s University.

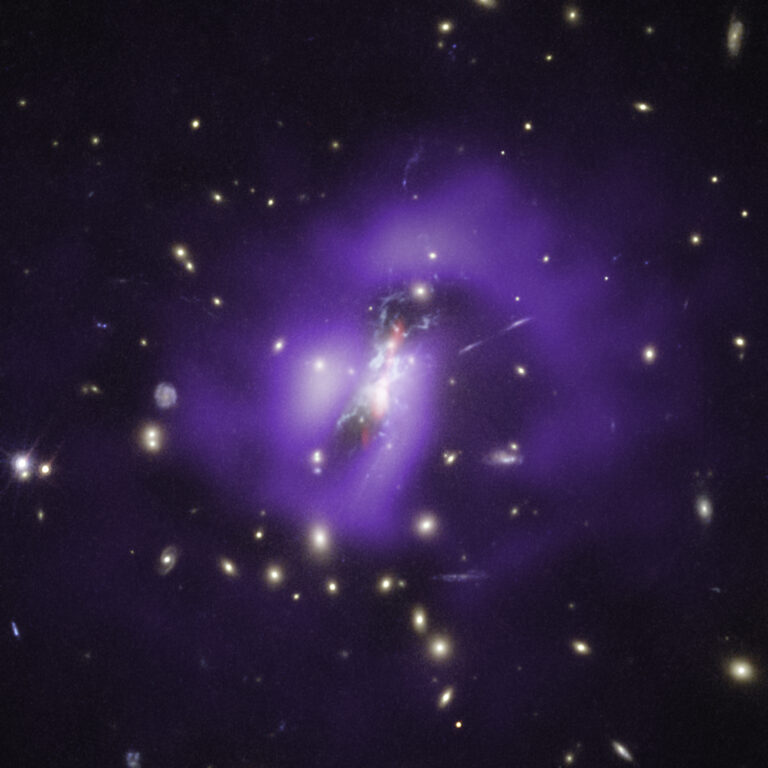

“We have studied the extended halos of individual galaxies for quite some time,” said Ralf-Jürgen Dettmar from Ruhr-University in Bochum, Germany. “The CHANG-ES sample will provide an additional statistical access to the important question of galactic feedback.” One of his prime research targets, NGC 5775, was used as a template in order to represent the inner star forming region of spiral galaxies.

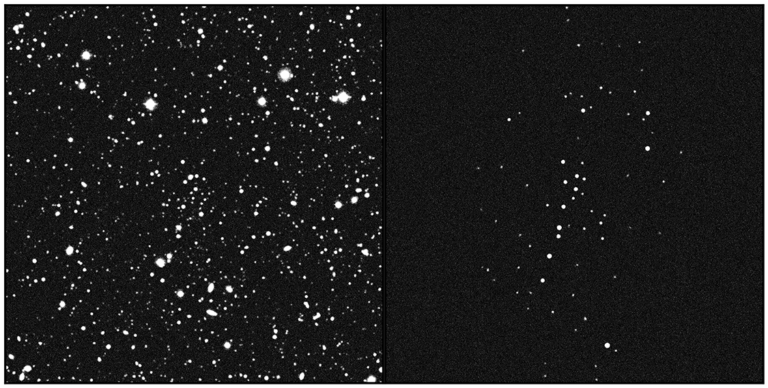

To see how extensive a “typical” halo is, the astronomers scaled their images of 30 of the galaxies to the same diameter, then another of the authors, Jayanne English of the University of Manitoba in Canada, combined them into a single image. The result, said Irwin, is “a spectacular image showing that cosmic rays and magnetic fields not only permeate the galaxy disk itself, but extend far above and below the disk.”

The combined image, the scientists said, confirms a prediction of such halos made in 1961.

Along with the report on their findings, the astronomers also are making their first batch of specialized VLA images available to other researchers. In previous publications, the team described the details of their project and its goals. The team has completed a series of VLA observations and their latest paper is based on analysis of their first set of images. They now are analyzing additional datasets, and also will make those additional images available to other scientists when they publish the results of the later analyses.

“The results from this survey will help answer many unsolved questions in galactic evolution and star formation,” said Marita Krause of the Max-Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany.