Key Takeaways:

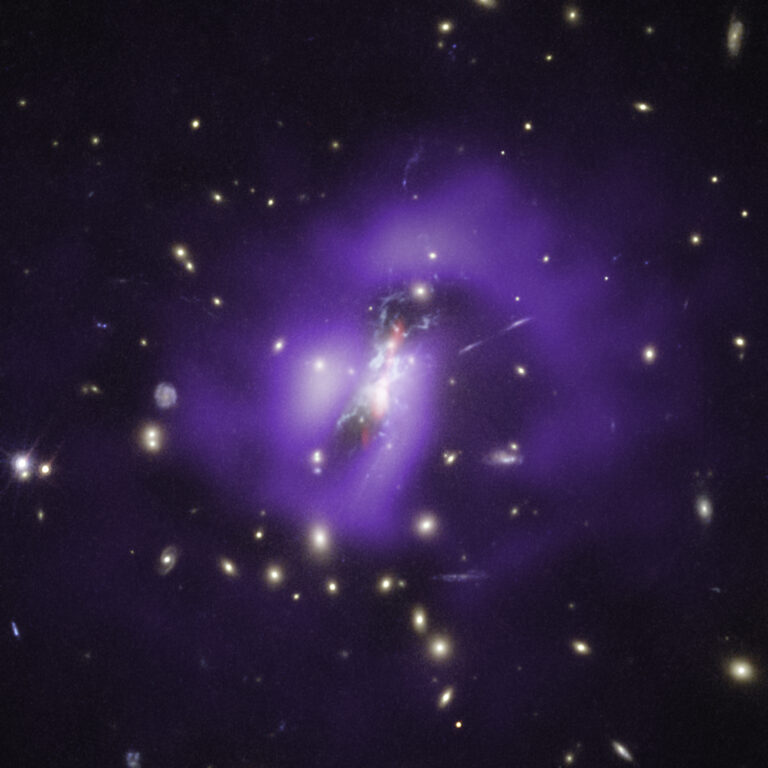

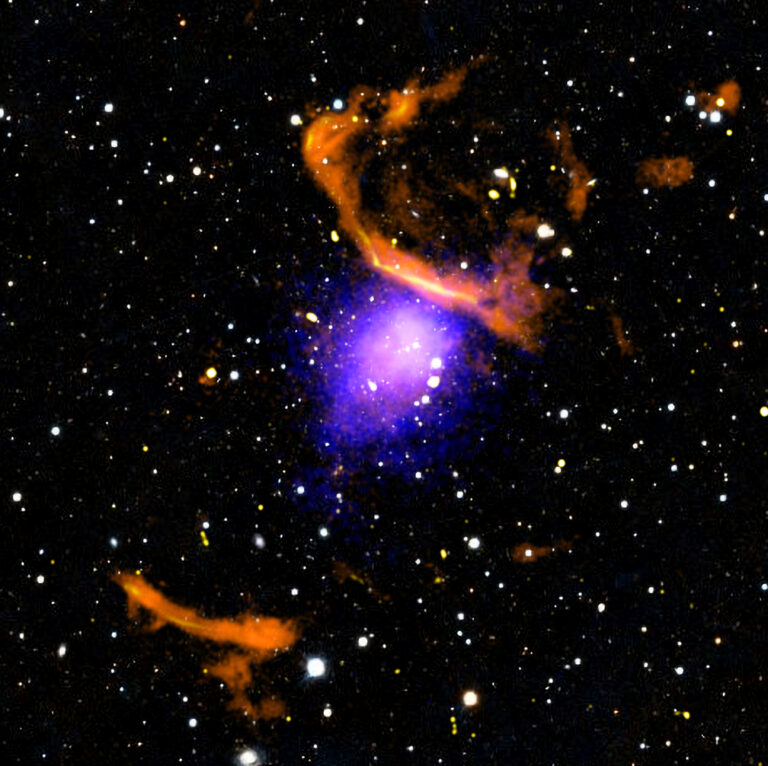

“If the Milky Way is a sea of stars, then these newly discovered galaxies are like wisps of clouds,” said van Dokkum. “We are beginning to form some ideas about how they were born, and it’s remarkable they have survived at all. They are found in a dense, violent region of space filled with dark matter and galaxies whizzing around, so we think they must be cloaked in their own invisible dark matter ‘shields’ that are protecting them from this intergalactic assault.”

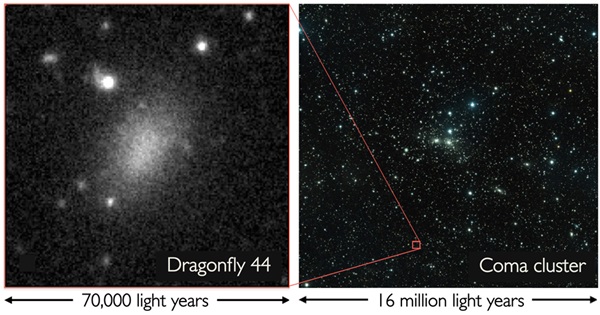

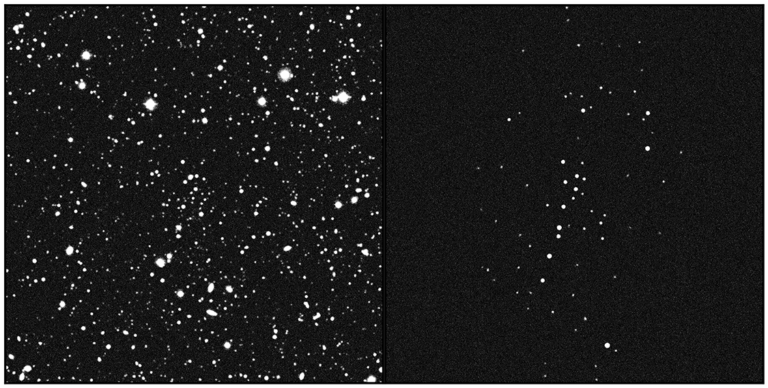

The team made the latest discovery by combining results from one of the world’s smallest telescopes as well as the largest telescope on Earth. The Dragonfly Telephoto Array used 14-centimeter state-of-the-art telephoto-lens cameras to produce digital images of the faint, diffuse objects. Keck Observatory’s 10-meter Keck I Telescope with its Low Resolution Imaging Spectrograph then separated the light of one of the objects into colors that diagnose its composition and distance.

Finding the distance was the clinching evidence. The data from Keck Observatory showed the diffuse “blobs” are large and far away, about 300 million light-years, rather than small and close by. The blobs can now safely be called Ultra Diffuse Galaxies (UDGs).

“If there are any aliens living on a planet in an ultra-diffuse galaxy, they would have no band of light across the sky, like our Milky Way, to tell them they were living in a galaxy. The night sky would be much emptier of stars,” said Aaron Romanowsky of San Jose State University.

The UDGs were found in an area of the sky called the Coma Cluster, where thousands of galaxies have been drawn together in a mutual gravitational dance. “Our fluffy objects add to the great diversity of galaxies that were previously known, from giant ellipticals that outshine the Milky Way to ultra compact dwarfs,” said Jean Brodie from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“The big challenge now is to figure out where these mysterious objects came from,” said Roberto Abraham of the University of Toronto. “Are they ‘failed galaxies’ that started off well and then ran out of gas? Were they once normal galaxies that got knocked around so much inside the Coma Cluster that they puffed up? Or are they bits of galaxies that were pulled off and then got lost in space?”

The key next step in understanding UDGs is to pin down exactly how much dark matter they have. Making this measurement will be even more challenging than the latest work.