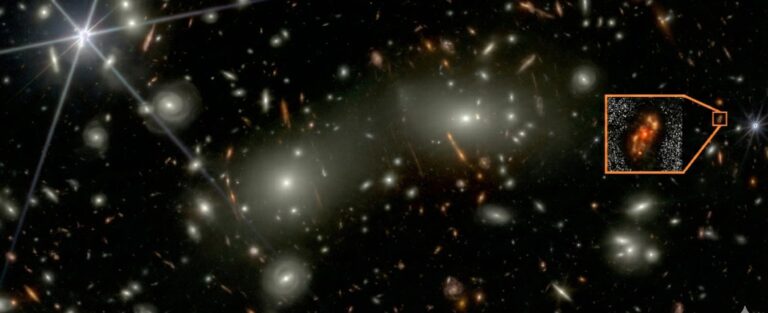

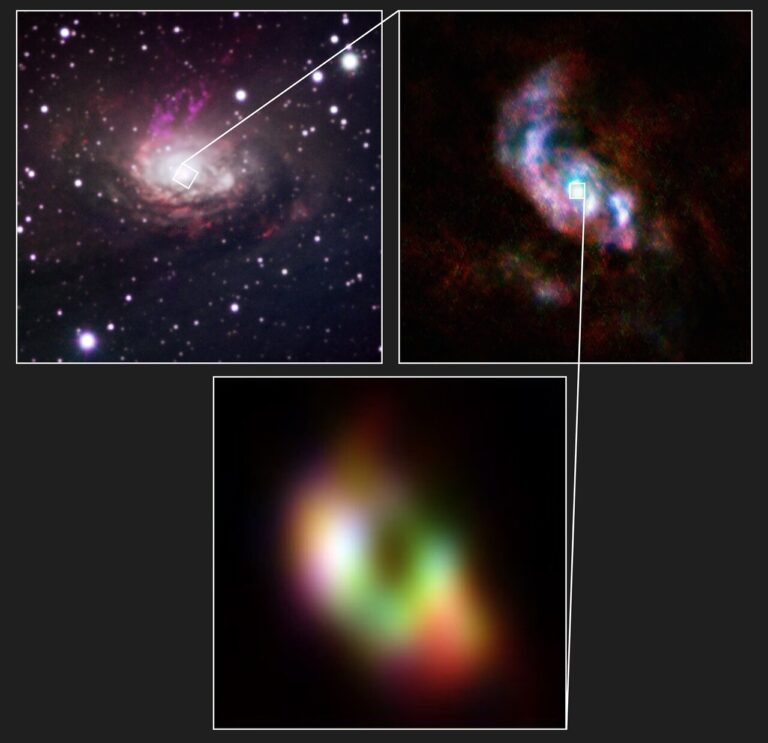

Since then, Chandra has returned its attention to this galaxy, each time gathering more data. And, like an old family photo that has been digitally restored, new processing techniques are providing astronomers with a new look at Cen A.

This new image of Cen A contains data from observations, equivalent to over 9.5 days worth of time, taken between 1999 and 2012. In this image, the lowest-energy X-rays Chandra detects are in red, the medium-energy X-rays are in green, and the highest-energy ones are in blue.

As in all of Chandra’s images of Cen A, this one shows the spectacular jet of outflowing material — seen pointing from the middle to the upper left — that is generated by the giant black hole at the galaxy’s center. This new high-energy snapshot of Cen A also highlights a dust lane that wraps around the waist of the galaxy. Astronomers think this feature is a remnant of a collision that Cen A experienced with a smaller galaxy millions of years ago.

The data housed in Chandra’s extensive archive on Cen A provide a rich resource for a wide range of scientific investigations. For example, researchers published findings in 2013 on the point-like X-ray sources in Cen A. Most of these sources are systems where a compact object — either a black hole or a neutron star — is pulling gas from an orbiting companion star. These compact objects form by the collapse of massive stars, with black holes resulting from heavier stars than those that produce neutron stars.

The results suggested that nearly all of the compact objects had masses that fell into two categories — either less than twice that of the Sun or more than five times as massive as the Sun. These two groups correspond to neutron stars and black holes.

This mass gap may tell us about the way massive stars explode. Scientists expect an upper limit on the most massive neutron stars, up to twice the mass of the Sun. What is puzzling is that the smallest black holes appear to weigh in at about five times the mass of the Sun. Stars are observed to have a continual range of masses, and so in terms of their progeny’s weight, we would expect black holes to carry on where neutron stars left off.

Although this mass gap between neutron stars and black holes has been seen in our galaxy, the Milky Way, this new Cen A result provides the first hints that the gap occurs in more distant galaxies. If it turns out to be ubiquitous, it may mean that a special, rapid type of stellar collapse is required in some supernova explosions.