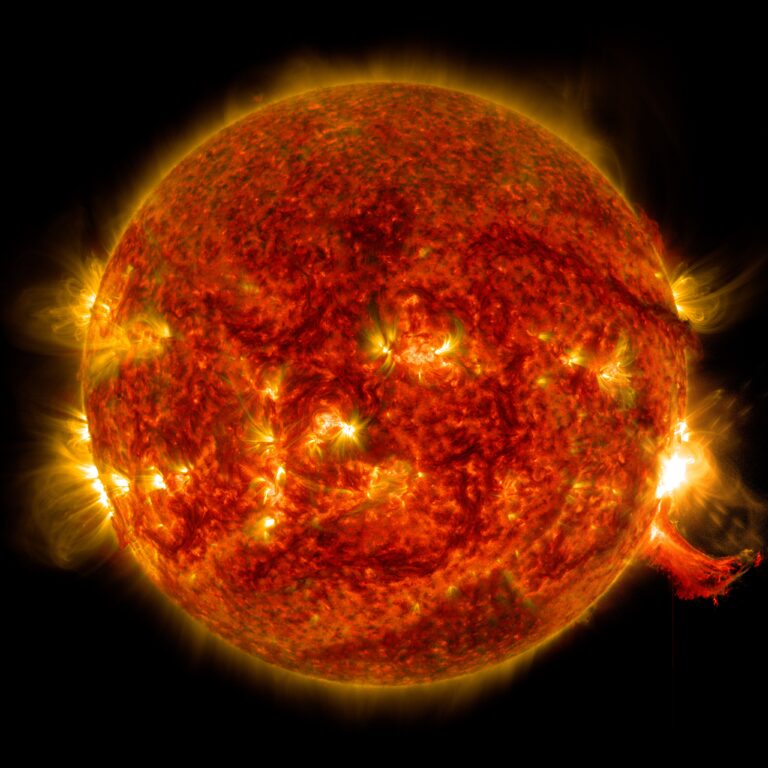

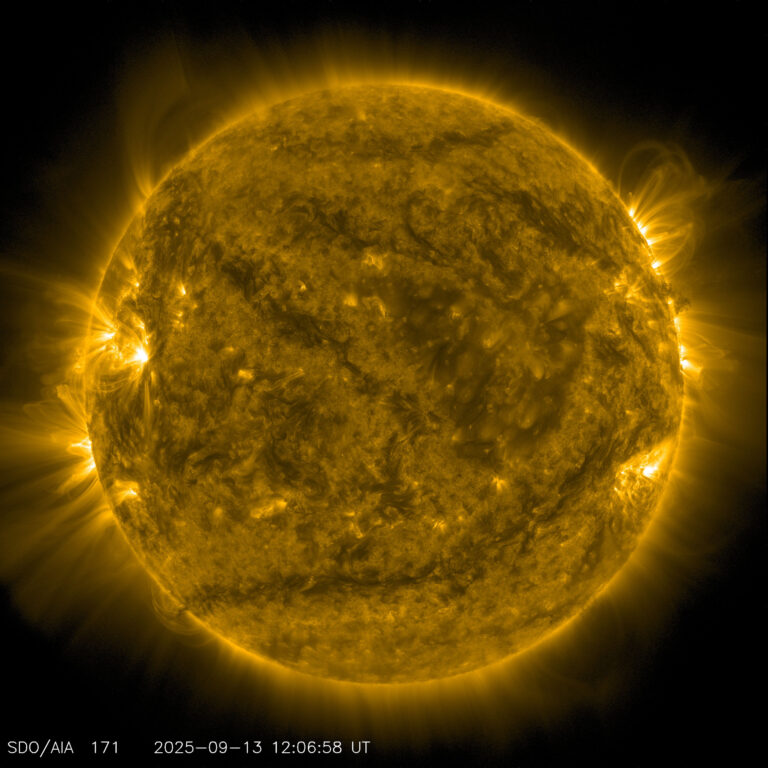

On its journey toward the Sun, Comet ISON has disappointed many hobby astronomers in the past weeks — its brightness did not increase as strongly as previously assumed. On November 28, 2013, the comet will fly by the Sun at a distance of only 1.1 million miles (1.8 million kilometers). However, on November 7, ISON’s light intensity increased abruptly; several observers announced a sudden rise in the comet’s activity.

Images of ISON taken by scientists from the MPS and the Wendelstein Observatory now offer possible evidence for the cause of this outburst. On November 14 and 16, the researchers aimed their telescope toward the approaching visitor.

The researchers’ images show two striking features within the comet’s atmosphere that protrude from the nucleus in a wing-like fashion. While these so-called coma wings were still rather faint on November 14, they dominate the images taken two days later. “Features like these typically occur after individual fragments break off the nucleus,” said Hermann Böhnhardt from MPS.

As does the nucleus, these fragments emit gas and dust. Where the emissions from the comet and its fragments meet, a kind of boundary layer is formed that often takes a wing-like form as seen from Earth. Whether or not this fragmentation process led to the recent outburst cannot be determined with certainty, said Böhnhardt. However, in the cases of other comets, a connection between both phenomena has been well established.

In the images taken of Comet ISON, the coma wings cannot be seen with the naked eye. Instead, numerical methods were necessary to make them visible. To this end, the researchers comb through the comet’s coma looking for spatial changes in the light intensity. The uniformly bright background of the comet’s atmosphere is numerically eliminated so as not to outshine the fainter structures hidden beneath. “Our calculations imply that ISON lost only one fragment or very few at the most,” said Böhnhardt.

How the comet will develop in the next weeks is still unclear. “However, according to past experience, comets that have once lost a fragment tend to do this again,” said Böhnhardt.