“The optical and ultraviolet light from stars continues to travel throughout the universe even after the stars cease to shine, and this creates a fossil radiation field we can explore using gamma rays from distant sources,” said Marco Ajello from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford University in California and the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

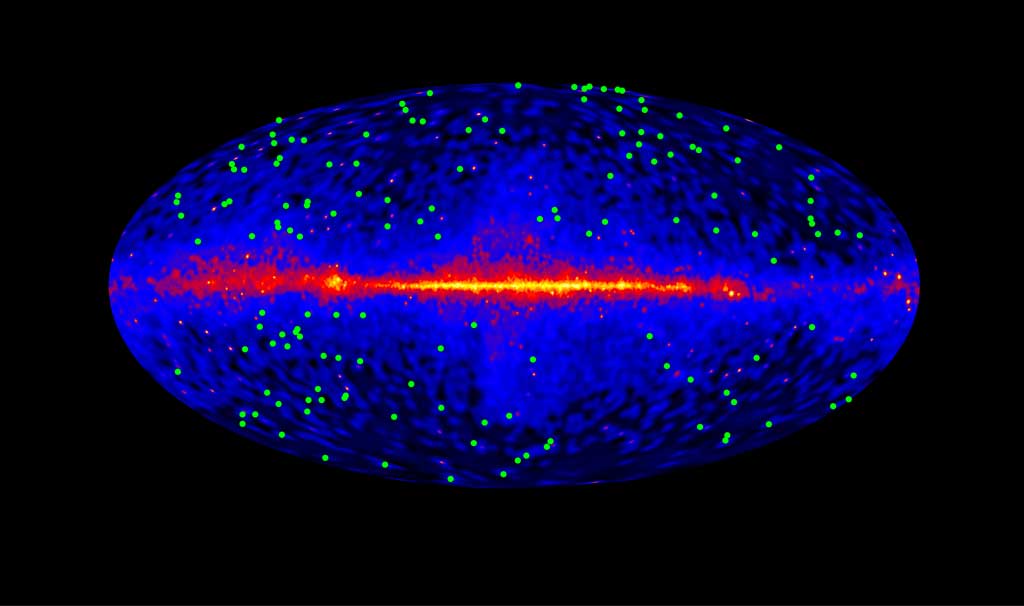

Gamma rays are the most energetic form of light. Since Fermi’s launch in 2008, its Large Area Telescope (LAT) observes the entire sky in high-energy gamma rays every three hours, creating the most detailed map of the universe ever known at these energies.

Astronomers know the total sum of starlight in the cosmos as the extragalactic background light (EBL). To gamma rays, the EBL functions as a kind of cosmic fog. Ajello and his team investigated the EBL by studying gamma rays from 150 blazars, or galaxies powered by black holes, that were strongly detected at energies greater than 3 billion electron volts (GeV), or more than a billion times the energy of visible light.

“With more than a thousand detected so far, blazars are the most common sources detected by Fermi, but gamma rays at these energies are few and far between, which is why it took four years of data to make this analysis,” said Justin Finke from the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C.

As matter falls toward a galaxy’s supermassive black hole, some of it is accelerated outward at almost the speed of light in jets pointed in opposite directions. When one of the jets happens to be aimed in the direction of Earth, the galaxy appears especially bright and is classified as a blazar.

Gamma rays produced in blazar jets travel across billions of light-years to Earth. During their journey, the gamma rays pass through an increasing fog of visible and ultraviolet light emitted by stars that formed throughout the history of the universe.

Occasionally, a gamma ray collides with starlight and transforms into a pair of particles — an electron and its antimatter counterpart, a positron. Once this occurs, the gamma-ray light is lost. In effect, the process dampens the gamma-ray signal in much the same way as fog dims a distant lighthouse.

From studies of nearby blazars, scientists have determined how many gamma rays should be emitted at different energies. More distant blazars show fewer gamma rays at higher energies, especially above 25 GeV, thanks to absorption by the cosmic fog.

The farthest blazars are missing most of their higher-energy gamma rays.

The researchers then determined the average gamma-ray attenuation across three distance ranges between 9.6 billion years ago and today.

From this measurement, the scientists were able to estimate the fog’s thickness. To account for the observations, the average stellar density in the cosmos is about 1.4 stars per 100 billion cubic light-years, which means the average distance between stars in the universe is about 4,150 light-years.

“The Fermi result opens up the exciting possibility of constraining the earliest period of cosmic star formation, thus setting the stage for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope,” said Volker Bromm from the University of Texas at Austin. “In simple terms, Fermi is providing us with a shadow image of the first stars, whereas Webb will directly detect them.”

Measuring the extragalactic background light was one of the primary mission goals for Fermi.

“We’re very excited about the prospect of extending this measurement even farther,” said Julie McEnery from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

This animation tracks several gamma rays through space and time, from

their emission in the jet of a distant blazar to their arrival in

Fermi’s Large Area Telescope (LAT). During their journey, the number of

randomly moving ultraviolet and optical photons (blue) increases as more

and more stars are born in the universe. Eventually, one of the gamma

rays encounters a photon of starlight and the gamma ray transforms into

an electron and a positron. The remaining gamma-ray photons arrive at

Fermi, interact with tungsten plates in the LAT, and produce the

electrons and positrons whose paths through the detector allows

astronomers to backtrack the gamma rays to their source. // Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Cruz deWilde