Key Takeaways:

“The spacecraft is right on target,” said Robert Mase from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “We look forward to exploring this unknown world during Dawn’s 1-year stay in Vesta’s orbit.”

After traveling nearly 4 years and 1.7 billion miles (2.7 billion kilometers), Dawn is approximately 96,000 miles (155,000 km) away from Vesta. When Vesta captures Dawn into its orbit July 16, there will be approximately 9,900 miles (16,000 km) between them. When orbit is achieved, they will be approximately 117 million miles (188 million km) away from Earth.

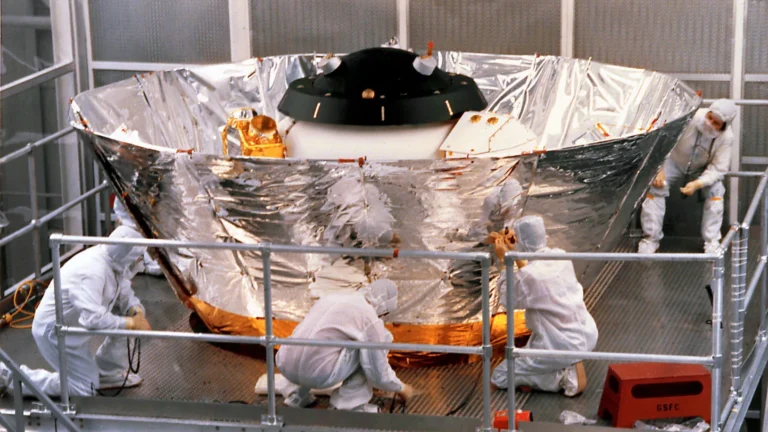

After Dawn enters Vesta’s orbit, engineers will need a few days to determine the exact time of capture. Unlike other missions where a dramatic, nail-biting propulsive burn results in orbit insertion around a planet, Dawn has been using its placid ion propulsion system to subtly shape its path for years to match Vesta’s orbit around the Sun.

Images from Dawn’s framing camera, taken for navigation purposes, show the slow progress toward Vesta. They also show Vesta rotating about 65° in the field of view. The images are about twice as sharp as the best images of Vesta from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, but the surface details Dawn will obtain are still a mystery.

“Navigation images from Dawn’s framing camera have given us intriguing hints of Vesta, but we’re looking forward to the heart of Vesta operations, when we begin officially collecting science data,” said Christopher Russell from the University of California, Los Angeles. “We can’t wait for Dawn to peel back the layers of time and reveal the early history of our solar system.”

Dawn’s three instruments are all functioning and appear to be properly calibrated. The visible and infrared mapping spectrometer, for example, has started to obtain images of Vesta that are larger than a few pixels in size. During the initial reconnaissance orbit, at approximately 1,700 miles (2,700 km), the spacecraft will get a broad overview of Vesta with color pictures and data in different wavelengths of reflected light. The spacecraft will move into a high-altitude mapping orbit, about 420 miles (680 km) above the surface to systematically map the parts of Vesta’s surface illuminated by the Sun; collect stereo images to see topographic highs and lows; acquire higher resolution data to map rock types at the surface; and learn more about Vesta’s thermal properties.

Dawn then will move even closer to a low-altitude mapping orbit approximately 120 miles (200 km) above the surface. The primary science goals of this orbit are to detect the byproducts of cosmic rays hitting the surface and help scientists determine the many kinds of atoms there, and probe the protoplanet’s internal structure. As Dawn spirals away from Vesta, it will pause again at the high-altitude mapping orbit. Because the Sun’s angle on the surface will have progressed, scientists will be able to see previously hidden terrain while obtaining different views of surface features.

“We’ve packed our year at Vesta chock-full of science observations to help us unravel the mysteries of Vesta,” said Carol Raymond from JPL. Vesta is considered a protoplanet, or body that never quite became a full-fledged planet.

“The spacecraft is right on target,” said Robert Mase from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “We look forward to exploring this unknown world during Dawn’s 1-year stay in Vesta’s orbit.”

After traveling nearly 4 years and 1.7 billion miles (2.7 billion kilometers), Dawn is approximately 96,000 miles (155,000 km) away from Vesta. When Vesta captures Dawn into its orbit July 16, there will be approximately 9,900 miles (16,000 km) between them. When orbit is achieved, they will be approximately 117 million miles (188 million km) away from Earth.

After Dawn enters Vesta’s orbit, engineers will need a few days to determine the exact time of capture. Unlike other missions where a dramatic, nail-biting propulsive burn results in orbit insertion around a planet, Dawn has been using its placid ion propulsion system to subtly shape its path for years to match Vesta’s orbit around the Sun.

Images from Dawn’s framing camera, taken for navigation purposes, show the slow progress toward Vesta. They also show Vesta rotating about 65° in the field of view. The images are about twice as sharp as the best images of Vesta from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, but the surface details Dawn will obtain are still a mystery.

“Navigation images from Dawn’s framing camera have given us intriguing hints of Vesta, but we’re looking forward to the heart of Vesta operations, when we begin officially collecting science data,” said Christopher Russell from the University of California, Los Angeles. “We can’t wait for Dawn to peel back the layers of time and reveal the early history of our solar system.”

Dawn’s three instruments are all functioning and appear to be properly calibrated. The visible and infrared mapping spectrometer, for example, has started to obtain images of Vesta that are larger than a few pixels in size. During the initial reconnaissance orbit, at approximately 1,700 miles (2,700 km), the spacecraft will get a broad overview of Vesta with color pictures and data in different wavelengths of reflected light. The spacecraft will move into a high-altitude mapping orbit, about 420 miles (680 km) above the surface to systematically map the parts of Vesta’s surface illuminated by the Sun; collect stereo images to see topographic highs and lows; acquire higher resolution data to map rock types at the surface; and learn more about Vesta’s thermal properties.

Dawn then will move even closer to a low-altitude mapping orbit approximately 120 miles (200 km) above the surface. The primary science goals of this orbit are to detect the byproducts of cosmic rays hitting the surface and help scientists determine the many kinds of atoms there, and probe the protoplanet’s internal structure. As Dawn spirals away from Vesta, it will pause again at the high-altitude mapping orbit. Because the Sun’s angle on the surface will have progressed, scientists will be able to see previously hidden terrain while obtaining different views of surface features.

“We’ve packed our year at Vesta chock-full of science observations to help us unravel the mysteries of Vesta,” said Carol Raymond from JPL. Vesta is considered a protoplanet, or body that never quite became a full-fledged planet.