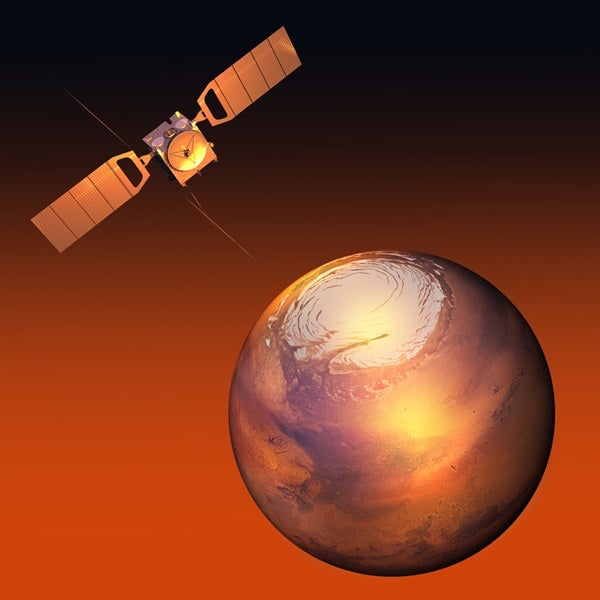

Today Mars Express began a series of flybys of Phobos, the largest moon of Mars. The campaign will reach its crescendo March 3 when the spacecraft will set a new record for the closest pass to Phobos, skimming the surface at just 30 miles (50 kilometers). The data collected could help untangle the origin of this mysterious moon.

The latest Phobos flyby campaign began yesterday, February 16, when Mars Express drew to within 616 miles (991 kilometers) of Phobos’ airless surface. The flybys will continue at varying altitudes until March 26 when Phobos moves out of range. They offer prime chances for doing additional science with Mars Express, a spacecraft that was designed to study the Red Planet below rather than the grey moon alongside.

“Because Mars Express is in an elliptical and polar orbit with a maximum distance from Mars of about 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers), we regularly pass Phobos. This represents an excellent opportunity to perform extra science,” said Olivier Witasse, Mars Express project scientist.

Back in 2009, the mission team decided that the orbit of Mars Express needed to be adjusted to prevent the closest approach of the spacecraft drifting onto the planet’s nightside. The flight control team at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, presented a number of possible scenarios, including one that would take the spacecraft to just 30 miles (50 kilometers) above Phobos. “That was the closest they would let us fly to Phobos,” said Witasse.

Precise Gravity Measurements

Heavy emphasis is being placed on the closest flyby because it is an unprecedented opportunity to map Phobos’ gravity field. At that range, Mars Express should feel a difference in the pull from Phobos, depending which part of the moon is closest at the time. This will allow scientists to infer the moon’s internal structure.

Previous Mars Express flybys have already provided the most accurate mass yet for Phobos, and the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) has provided the volume. When calculating the density, this gives a surprising figure because it seems that parts of Phobos may be hollow. The science team aims to verify this preliminary conclusion.

In particular, the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) will operate in a special sequence to try to see inside the moon, looking for structures or some clue to the internal composition. “If we know more about how Phobos is built, we might know more about how it formed,” said Witasse.

The origin of Phobos is a mystery. Three scenarios are possible. The first is that the moon is a captured asteroid. The second is that it formed in situ as Mars formed below it. The third is that Phobos formed later than Mars, out of debris flung into martian orbit when a large meteorite struck the Red Planet.

All the instruments will be used during the campaign, including the HRSC. Although no imaging will be possible during the first five flybys, including the closest one, because Mars Express approaches from the nightside, high-resolution pictures will be possible from March 7 onwards. One task for HRSC is to image the proposed landing sites for the Russian mission Phobos-Grunt.

“It is always busy,” said Witasse about running the science mission. “The Phobos flybys make it even more exciting.”