Call your friends. It’s time once again for the annual Perseid meteor shower, typically the greatest shower of the year. This event occurs during the Northern Hemisphere summer, so even many people who don’t consider themselves astronomers venture outdoors to watch it.

The Perseids feature a slow (two-week) buildup to maximum (along with an equally slow decline to zero activity), and many bright meteors that leave luminous trails visible for several seconds. The trails form because Perseid meteors are fast — their speeds top 125,000 mph (200,000 km/h). Usually, Perseid meteors appear white or bluish white.

In 2018, the New Moon fortuitously occurs August 11, so our normally brilliant satellite will be absent during the shower’s peak, which falls on the night of August 12 and the morning of the 13th. If you see the Moon at all, it will be a thin crescent low in the western sky that will set an hour or so after the Sun. Perhaps the only negative about this year’s Perseids is that the peak occurs on a Sunday night into Monday morning, so work commitments may limit the number of people who actually view the shower.

For many amateur astronomers, one of the best things about the Perseids comes from getting together with like-minded friends for fun under the stars. Few astronomical viewing sessions promise the drama of a brilliant fireball (a meteor that casts a shadow) or bolide (an exploding meteor), but meteor showers can feature such events. You’ll know real excitement if you experience a bright meteor with a group of people.

Most astronomy clubs host observing sessions either on the night of the shower’s predicted maximum or on a weekend night close to it. If you’re not doing serious meteor counting, all you’ll need to bring is a lawn chair, some snacks, and your eyes.

Telescopes do a great job of magnifying objects, but they severely restrict your field of view, a negative for meteor watching. Binoculars also restrict your view, so don’t observe the shower through them. Instead, if you have binoculars nearby, you can use them to catch a close-up view of a meteor’s smoke trail after spotting it with your naked eye.

What’s going on?

Meteors are tiny dust-size particles of rock and metal that Earth passes through as it orbits the Sun. Astronomers call these particles meteoroids when they are floating freely in space, but when they burn up in the atmosphere, they become meteors. If they survive the fiery ordeal of passage through our thick blanket of air to land on the ground, they are then known as meteorites. No meteorites come from meteor showers — the particles are too small.

Most meteor showers originate with comets. When a comet swings around the Sun, our star’s heat boils off ice and with it, trapped dusty debris. When the debris trail’s orbit crosses Earth’s orbit, we experience a meteor shower. The exception to the comet rule is the Geminid shower, which occurs in December. That event’s particles originate with dust coming from the asteroid 3200 Phaethon.

Astronomers designated the Perseids’ parent comet as 109P/Swift-Tuttle. The number identifies it as the 109th periodic comet whose orbit astronomers have calculated. The common name comes from the discoverers, Lewis Swift of Marathon, New York, and Horace Parnell Tuttle, who worked at Harvard Observatory in Massachusetts. Each discovered the comet in July 1862. It shone at magnitude 7.5 at the time of the discovery and brightened to about magnitude 2 by early September. It sported a tail between 25° and 30° long and was quite impressive. The comet visits our part of the solar system every 133 years. In November 1992, it brightened to 5th magnitude and was visible without optical aid only from the darkest sites. During its next close passage in 2126, it will shine slightly brighter than 1st magnitude.

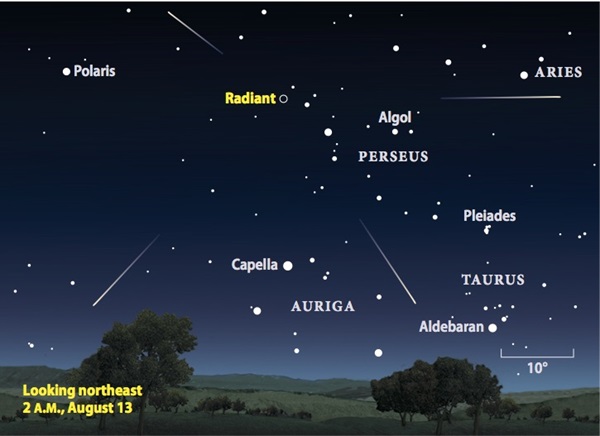

By the way, astronomers call this particular shower the Perseids because if you trace all the meteor trails backward, they meet within the boundaries of the constellation Perseus the Hero. The point of origin (the direction in space toward which Earth is heading) is called the radiant. A good visual approximation of the radiant is the famous Double Cluster in Perseus (NGC 869 and NGC 884).

2018 forecast

Scientists who study meteor showers predict the Perseids will peak between 4 p.m. EDT August 12 and 4 a.m. EDT August 13. Based on these times, meteor watchers in the United States who can spend the night outdoors should begin observing at the end of astronomical twilight on the 12th and watch the sky until dawn.

August 12 isn’t the only night you can observe Perseids. This year, the shower will be active between about July 17 and August 24. Of course, you’ll see fewer meteors the further you observe from the date of the peak.

Early in the evening on August 12, set up a lawn chair (preferably one that reclines), face east, and look a third to half of the way up in the sky. Bright meteors that travel near the top of the atmosphere and leave long trails are more common at this time. As the radiant rises (remember, you can use the Double Cluster to approximate it), adjust your gaze to keep watching a point about 45° west of it. Glancing around is OK. In the early morning hours, after the radiant has crossed the meridian — the imaginary line from north to south that divides the eastern half of the sky from the west — and begins to sink lower in the northwest, you might want to change your view and look 45° east of the radiant.

If you’re observing in a group, let those around you know when you spot a bright Perseid. Some meteor trails last for several seconds, and glowing trains may remain long after the meteors’ light fades.

How many Perseids will you see? Meteor counters use a quantity called the zenithal hourly rate (ZHR). This is the number of meteors visible per hour for an observer under a dark sky with no scattered light and with the radiant positioned directly overhead. The ZHR for the Perseids is 110. This year, with the Moon out of the sky, you can expect to count between 80 and 90 meteors per hour from a dark site — a terrific rate!

All meteor showers are exciting events, but this summer’s Perseids rank at the top. Be comfortable, have fun, and get ready for some oohs and aahs.

Astronomy Senior Editor Michael E. Bakich has spent countless summer nights through the years observing the Perseids.