Q: How do astronomers know how long to make an exposure of any given object?

A: To get a good estimate of the exposure times for a target, astronomers need to understand the telescope and instrument characteristics as well as the requirements of their own scientific measurements.

How well an instrument-telescope combination generally performs depends on the scope’s size, the detector’s sensitivity (which is just how many photons of light the system can detect per second when observing an object of a given brightness), and the sources of “noise” (which can obscure the data). Some of the noise sources are internal and may not depend on the exposure time, such as the readout noise on a CCD detector; this is a consequence of the system converting and reading electronic signals. Other sources of noise do depend on the exposure time, like the noise from the sky background. The measurement of the object itself also has noise, which is often called “shot noise.” (Generally, the amount of shot noise relates directly to the number of photons captured.)

Astronomers — armed with this noise information, the brightness of their astronomical targets, and the goal of the science they are planning to do — calculate the required exposure time to achieve a specific signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) on that target. For some types of science, like galaxy searches, the S/N can be low, maybe 3 to 5. (A S/N of 3 means the target’s signal is three times brighter than the noise.) For other types of science, like searching for exoplanets by how they tug on their parent stars, the S/N needs to be much higher, perhaps 100 or 1,000.

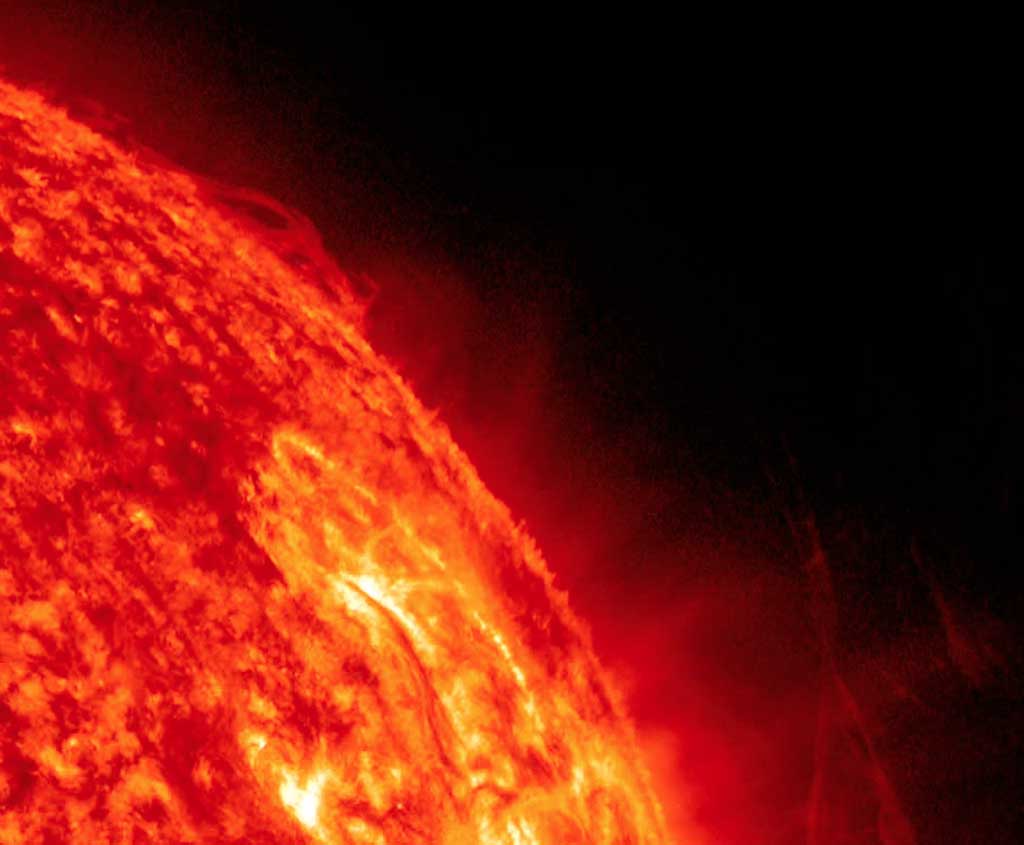

In some situations, other criteria are at work. For example, rapidly changing objects might allow only for a short exposure time before the object changes. To get a high enough S/N, the astronomer might have to take many short exposures and combine the results. In other situations, the scientist must find a larger telescope or a more sensitive instrument to get the required data.

W. M. Keck Observatory,

Mauna Kea, Hawaii