Key Takeaways:

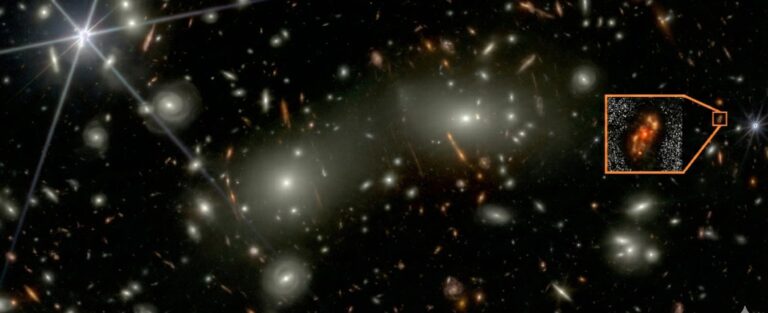

The major goal for JWST is to observe the first stars and galaxies in the universe. And that’s where the need for a large space telescope that can detect infrared radiation comes in. These objects lie so far away that the expanding cosmos shifts their light far to the red. Astronomers measure the amount of this change, the so-called redshift, to determine how far away an object lies. A galaxy with a redshift of 1 has had its light shifted by 100 percent — in other words, the wavelengths it emits have doubled — and lies halfway across the universe, about 7 billion light-years away.

But to go back to the era when stars and galaxies were forming requires looking 10 billion to more than 13 billion light-years away. The redshifts then can be 5 or more. A galaxy at a redshift of 5, for example, has the wavelengths of its light shifted by 500 percent. That means even ultraviolet radiation at a wavelength of 0.3 micrometer will be shifted into the near-infrared, at a wavelength of 1.8 micrometers.

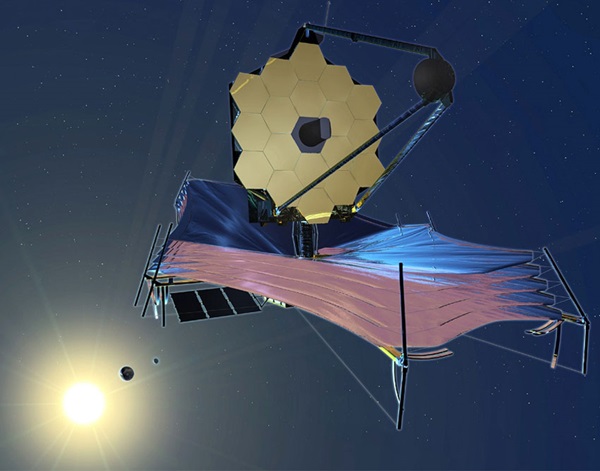

To accomplish its mission, JWST will employ a 6.5-meter (20 foot) mirror, nearly 3 times the diameter of Hubble’s mirror and more than 7 times that of Spitzer’s. New technology means the mirror, which consists of 18 segments made primarily of beryllium, weighs just a third of Hubble’s primary mirror. The mirror will deliver a resolution of about 0.1″, comparable to Hubble.

After launch, scheduled for no earlier than June 2013, JWST will be placed in an orbit around the L2 Lagrangian point of the Sun-Earth system. This spot lies on a line from the Sun to Earth that extends about a million miles farther into space beyond our planet. An object at the L2 point will stay in place relative to both the Sun and Earth, so JWST will keep up with Earth as our planet orbits the Sun. Observing from L2 provides a stable thermal environment and keeps the three objects whose light would most interfere with observations — the Sun, Earth, and Moon — all in the same direction. The scope will have a sunshield the size of a tennis court to protect its sensitive instruments. NASA is already using the L2 point for the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), which revolutionized our knowledge of the cosmic background radiation. With any luck, the James Webb Space Telescope will prove equally adept at helping astronomers understand how galaxies form and evolve.

A fly in the JWST ointment has recently arisen because cost estimates have ballooned to the point where they now far exceed the program budget. The increases come from a combination of additional required work, a slippage in the launch schedule, a delay in deciding to go with an Ariane 5 launch vehicle provided by ESA, and increased reserves required to meet NASA standards. The JWST project is currently evaluating technical options before NASA decides how to restructure the telescope to provide the best mission.