Key Takeaways:

- Historical observations by Tycho Brahe (1572) and Johannes Kepler (1604) documented the transient appearance of "new stars," later identified as supernovae, which profoundly challenged prevailing static cosmological models.

- The perception of "lost" stars can arise from perceptual challenges, as exemplified by the mythical "Lost Pleiad" within the M45 cluster, or from intrinsic stellar variability, such as the significant magnitude fluctuations of Mira-type pulsating red giants.

- Inaccuracies in historical astronomical catalogs, exemplified by Messier's misidentified M47, and the reclassification of celestial regions, leading to the obsolescence of constellations such as Robur Carolinum, have also resulted in "lost" objects or groupings.

- Modern initiatives, including Project VASCO, are investigating candidates for genuinely vanishing stars that leave no traditional remnants, considering hypotheses such as direct stellar collapse into black holes or advanced technological concealment, highlighting the universe's inherent dynamism.

Star maps and charts are a mainstay of both amateur and professional sky observers. Whether it’s on a simple seasonal map or in a comprehensive atlas, the stars listed appear steadfast and constant.

Yet there are stars that have appeared in these publications and then vanished. Some have been misplaced or even just imagined. Understanding how stars can be lost — and sometimes found — is like reading an intriguing mystery.

Nova stella

On a cold November night in 1572, the young astronomer Tycho Brahe was walking home. It had been cloudy for a few nights but was now clear. Tycho knew the stars well and was scanning the sky when he saw a star in the constellation Cassiopeia that he had not seen there before. Tycho had been raised and educated in Aristotelian, geocentric cosmology. The Church taught that the universe was eternal and unchanging. So how could a new star appear in the heavens?

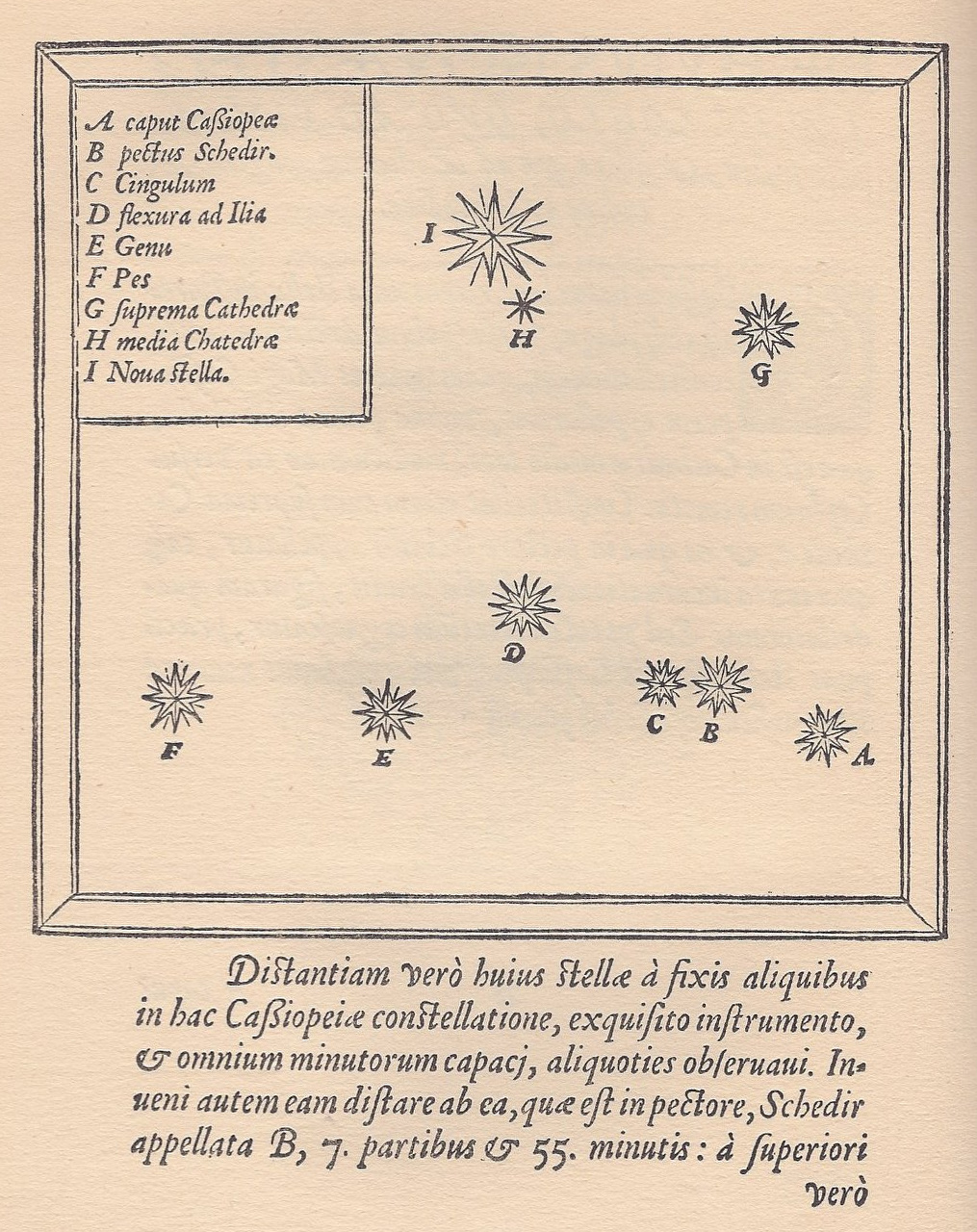

Tycho and other astronomers carefully measured the position of the new star. In 1573, he published a book titled De Nova Stella, extolling his observations and ideas about this astounding star. He included a star map of Cassiopeia denoting the nova with the letter I. Observations from across Europe helped to determine that the new star was in a sphere well beyond the Moon, shaking the foundations of astronomy.

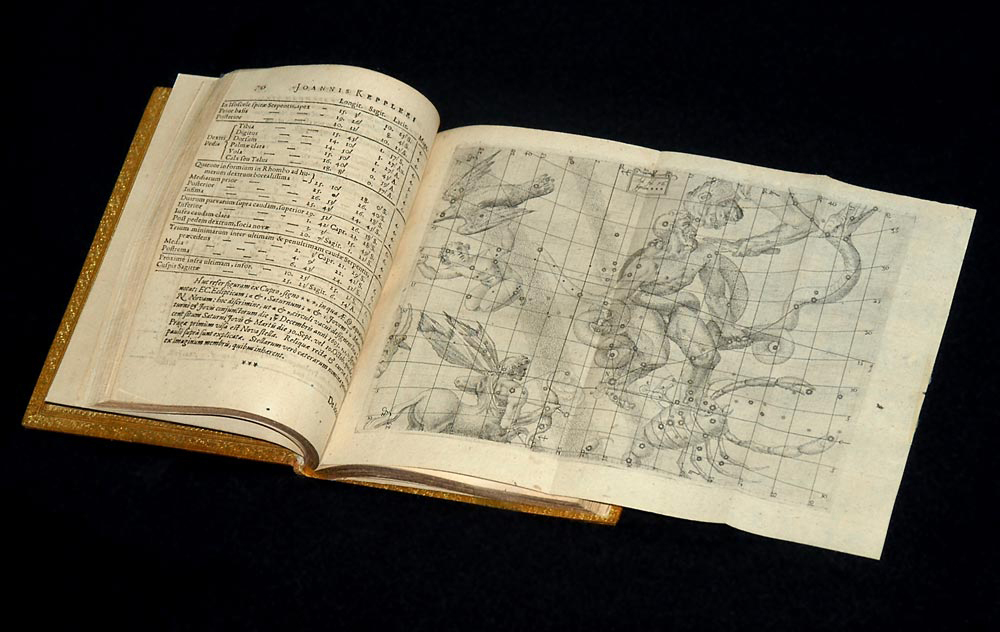

By 1574, Tycho’s star had faded from view and was seemingly lost forever. But 32 years later a similar story played out all over again. In the autumn of 1604, Johannes Kepler, astronomer and astrologer to Emperor Rudolph II, was awakened in the middle of the night to a story of a new star glimpsed through the cloudy skies of Prague. By Oct. 17, the clouds were gone and Kepler saw the new star shining brightly in the constellation Ophiuchus. Kepler was not the first to see this new star, but his observations and ideas would be significant. Tycho Brahe had achieved fame with his star, and now Kepler had his chance.

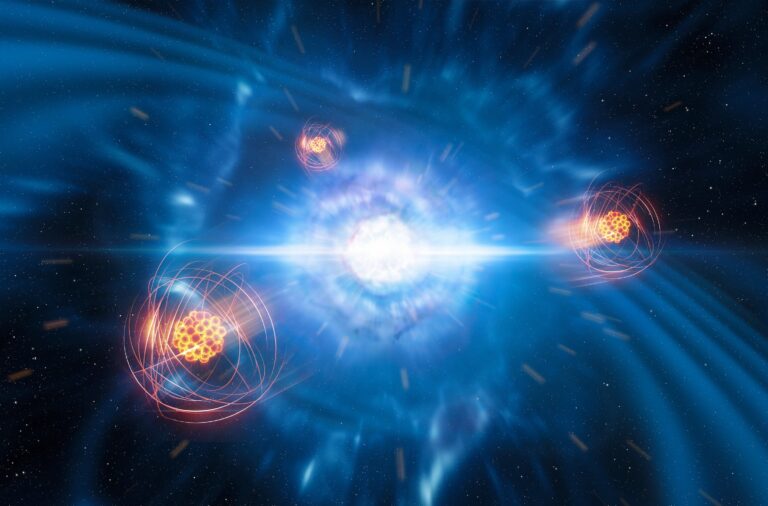

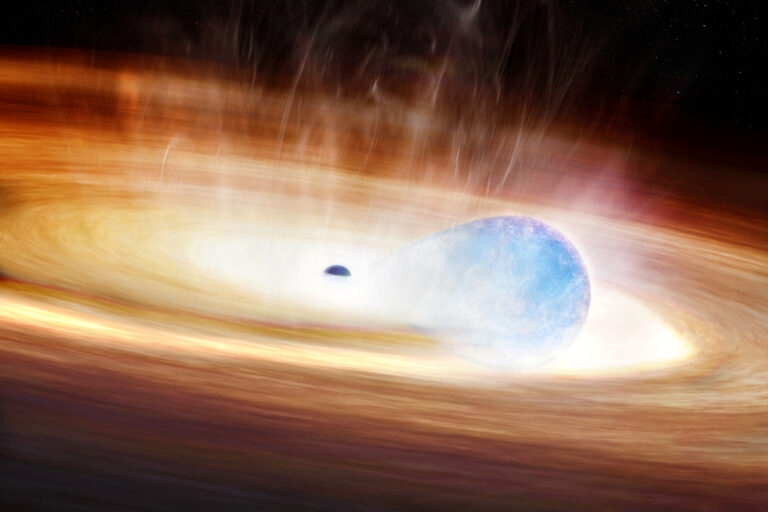

Visible low in the southwest, the star appeared just above Jupiter. Mars and Saturn were also part of the celestial show. In his 1606 book De Stella Nova in Pede Serpentarii, Kepler supported the idea that his new star was also far beyond the Moon. As with Tycho’s star, this apparition faded from view and was lost to observers. We now know that both new stars were type I supernovae.

Celestial confusion

Looking like diamonds in the sky, the Pleiades (M45) are perched on the back of Taurus the Bull. This cluster has one of the longest histories of documentation of any star group. Its brightest stars are regarded as seven sisters or maidens in many cultures.

According to Greek myth, these stars represent the seven daughters (Alcyone, Asterope, Celaeno, Electra, Maia, Merope, and Taygeta) of Atlas and Pleione, all of whom have named stars in the cluster. On a clear moonless night, the unaided eye can perceive stars as faint as 6th or 7th magnitude. The brightest Pleiads range from about 3rd magnitude to the edge of visibility at 6th magnitude. Most people can see at least six, but not everyone can easily see all seven, leading to myths worldwide about the “lost Pleiad.”

But which Pleiad is the elusive one? Three have been suggested. Electra looms large in stories of Troy and its destruction. Legends say that as the city burned, she covered her face with a veil, making it difficult to see her. At magnitude 3.7, however, her star is fairly easy to spot in a dark sky.

Merope is most often associated with the lost Pleiad. She shamed her parents by marrying a mortal and then hid herself in shame. However, like Electra, Merope’s star should be visible without much effort at magnitude 4.2.

Pleione, the girls’ mother, may actually be the best candidate. To see this star, you need a truly dark sky and sharp eyes. Pleione can be hard to spot because it is nestled only 5′ from Atlas. Pleione is also a variable star, ranging from magnitude 4.7 to 5.5. Could this be the missing star? The mystery may never be solved.

Cosmic hide and seek

Some stars like to play peek-a-boo. One of the most famous is the variable star Mira (Omicron [ο] Ceti) in Cetus the Whale. Mira is a pulsating variable star that fluctuates between 2nd and 10th magnitude. Its variable nature was discovered by David Fabricius in August 1596. He chose Omicron in Cetus as a reference star to help track what he thought was the planet Mercury.

At the beginning of the month, the star was about 3rd magnitude but in a matter of weeks, it increased to 2nd magnitude. Over the next few months, the star faded and disappeared and was lost from view. The invention of the telescope was still more than a decade away, so Fabricius had no way of observing the star at its faintest.

The 17th-century astronomer Johannes Hevelius worked out the star’s 11-month cycle and named it Mira, which means “wonderful.” We now know that Mira is a 6-billion-year-old red giant star nearing the end of its life. Other Mira-type stars can be followed through their disappearing acts. Chi (χ) Cygni pulsates from an easily visible magnitude 3.3 to an incredibly faint 14th magnitude. Not far from Regulus (Alpha [α] Leonis) is another red giant, R Leonis, that swings between 4th and nearly 12th magnitude every 312 days.

Until astronomers came to grips with the physics of stellar evolution and understood what powers such stars’ cycles of variability, these stars were truly lost and found again and again.

Cosmic confusion

A star doesn’t need to disappear to confuse astronomers, however. Sometimes, recording and naming celestial objects can create problems. For example, Charles Messier’s famous catalog of 109 “fuzzy” objects contains a few mysteries. Today, M47 in the constellation Puppis is listed as a galactic star cluster. Messier described it as a fairly bright cluster not far from M46. However, using Messier’s coordinates to search for this object reveals no cluster at all — it seems to have been lost.

In the late 19th century, the astronomer J.L.E. Dreyer began to sort out the astronomical catalogs compiled by Messier, William Herschel, Lord Rosse, and others. It must have been a daunting task. Dreyer assigned a star cluster very close to M46 as NGC 2478. Messier, or those who copied his catalog for publication, may have provided faulty coordinates; NGC 2478 is now assumed to be what Messier originally observed. Dryer’s original New General Catalogue contained nearly 8,000 objects, but it also incorporated duplications and errors made by past observers. The Revised NGC Catalogue has been corrected and updated, solving many mistakes and mysteries like M47.

Using your imagination

Sometimes the stars themselves don’t disappear but what they represent does. Every culture has used imagination to populate the sky with constellations. There are now 88 official constellations, but that hasn’t always been the case. The ancient Greeks visualized 48 constellations. All but one — Argo Navis — still endure on modern star charts. Over the centuries, European astronomers added more constellations, some of which remain while others have been lost.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw many constellations added to the original 48. French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille came up with 14. Edmond Halley, of comet fame, created Robur Carolinum (Charles’ Oak) in honor of England’s Charles II. (During the English Civil War, Charles hid in a great oak tree to escape capture.) Halley wanted to impress the king who had paid for his expedition to the Southern Hemisphere by giving Charles a place in the heavens. The Oak was near Argo Navis in the southern sky. Both are now lost and mostly forgotten, their stars reassigned to other constellations by later astronomers.

Searching for light

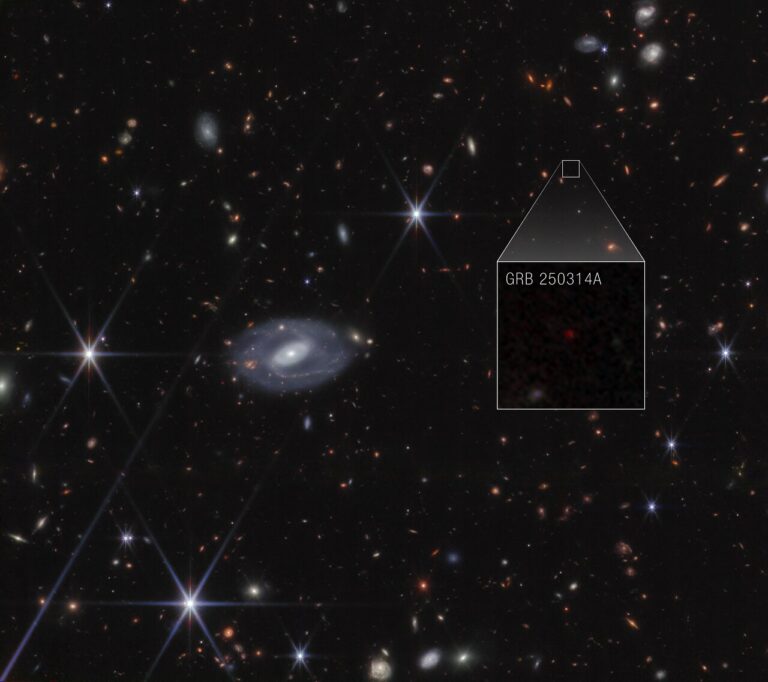

Constellations may vanish from star maps, but the stars remain. Or do they? At the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Stockholm, Sweden, a team of researchers led by Beatriz Villarroel is searching for stars that may have vanished. Project VASCO (Vanishing and Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations) is designed to search for these missing stars.

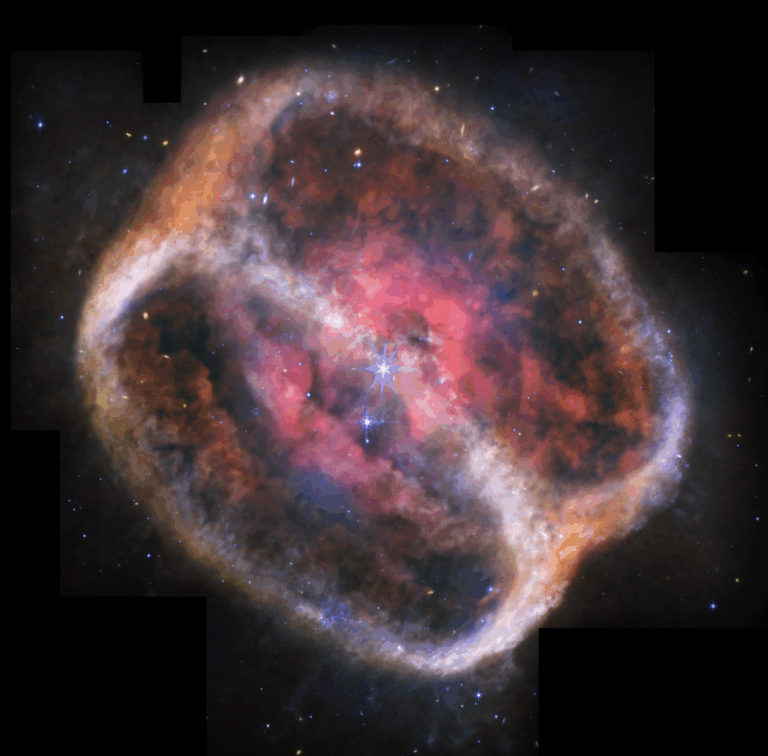

Most disappearing stars, like Tycho’s star of 1572, have been found. The expanding shell of Tycho’s star was pinpointed by radio astronomers at Jodrell Bank Observatory in England in 1952. Even the supernova of 1054, which created the Crab Nebula (M1), has been pinned down. These disappearing stars and others like them have left traces. But can a star vanish without leaving any evidence that it ever existed?

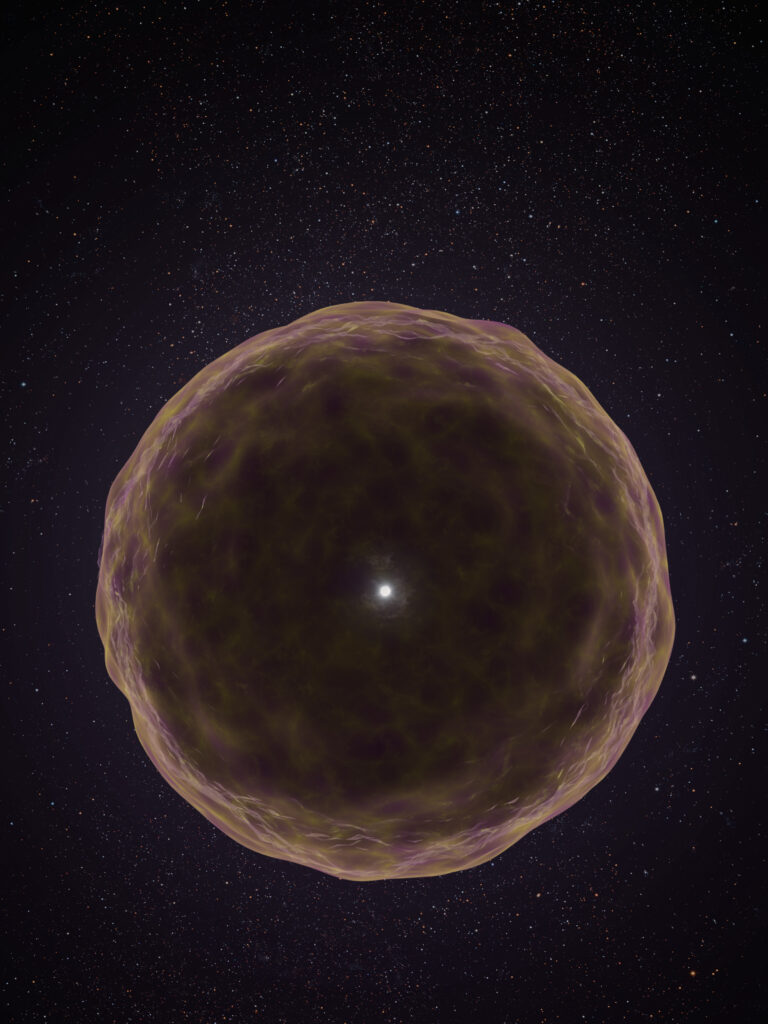

Villarroel and her team have found around 800 candidates for vanishing stars. Many of these may be supernovae, but there are some other intriguing suggestions to explain why some stars leave no trace when they disappear. Some supermassive stars might collapse rapidly into black holes. Another idea invokes an advanced alien civilization surrounding its home star with a Dyson sphere, capturing all of its energy but blocking the radiant light of the star.

When viewing a beautiful star-filled sky, we feel calm about the apparent unchanging nature of the universe. That feeling is shattered when “new” stars appear or vanish. But we now understand that the universe is dynamic: In the cosmos, nothing lasts forever and many mysteries wait to be solved. Bright stars may not be steadfast after all, but our curiosity is.