Key Takeaways:

- Astigmatism correction is most effectively achieved with hard gas permeable contact lenses, which reshape the cornea. Glasses provide comparable correction, superior to standard soft contacts, and at least equivalent to toric soft contacts.

- Averted vision, a technique involving slightly offsetting gaze from the object of observation (e.g., 10 or 2 o'clock position in the field of view), enhances visibility of faint celestial objects by circumventing the eye's central blind spot.

- Eye fatigue during astronomical observation can be mitigated by short, regular breaks incorporating simple eye exercises, such as focusing on a different object, gently cupping the eyes, or performing eye rolls followed by brief periods of rest.

- Individual preferences may influence the optimal averted vision technique, with variations in gaze direction (e.g., slightly above or below the target) noted among observers.

When you set up your telescope, you want to give yourself the best chance to make successful observations. Top-notch equipment will certainly help, but another key is knowledge. Here are a few things about the eye that I’ve learned through the years. OK, decades.

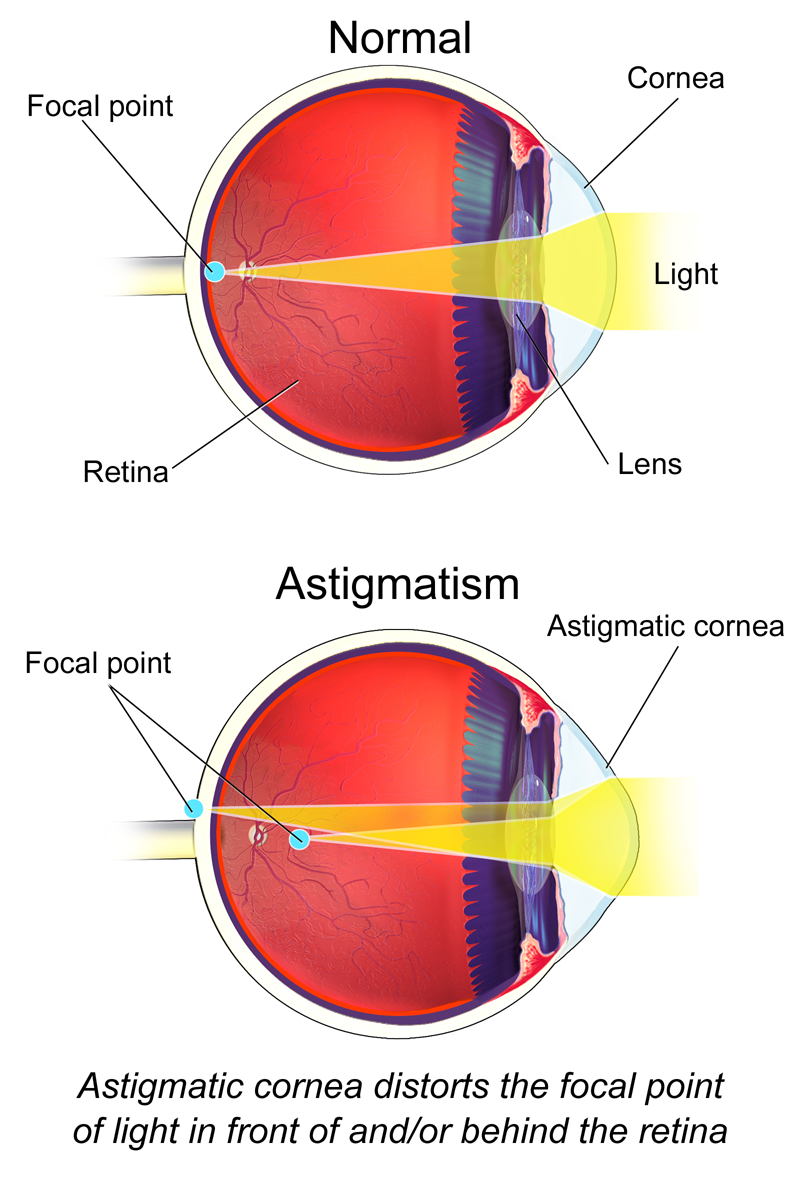

Astigmatism

The best corrective device for astigmatism seems to be hard gas permeable contacts because they force the corneal curvature to match the inner surface of the contact. If your eyes are tolerant to hard contacts, they remove the effect of corneal surface aberrations. However some folks can’t tolerate hard contacts. Soft contacts take the shape of the cornea they’re placed on, so they will not correct for astigmatism unless they are the toric design with weights to keep proper orientation of the correction. A quality pair of glasses is close or equal to hard contacts, superior to plain soft contacts, and equal to or better than the toric design soft contacts.

Averted Vision

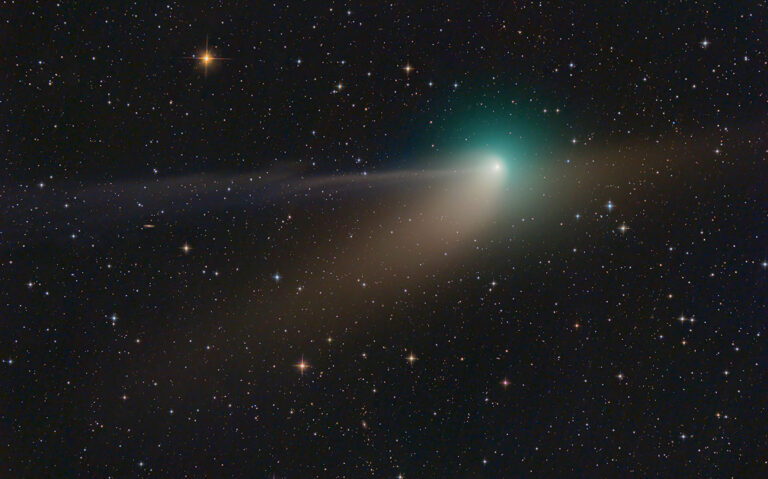

When observers look at faint objects through their telescopes, the best views often come by not looking directly at the object. That’s because the nerve endings in the eye are clustered in the center, which creates a small blind spot. We don’t notice this when we’re looking at large or well-lit things, as we do during the daytime. Moving that blind spot a tiny bit — a technique called averted vision — gives us the best chance to pick out details. Averted vision seems to work best when you place the object either at 10 o’clock or 2 o’clock in your telescope’s field of view. An inexperienced observer has little chance of seeing, for example, the Horsehead Nebula or each member of Stephan’s Quintet — no matter how good their eyes are — if they don’t use averted vision.

My friend, Brian Skiff, of Flagstaff, Arizona, adds, “The easy way to remember is to place the object between your nose and the direction you are looking. Folks seem to vary as to whether looking slightly above or below is best —there may be some normal variation, or it may be part of what you get used to. Being left-eyed, I tend to look left-down for averted vision, but I usually also try left-up.”

Avoiding Eye Fatigue

One of the best things you can do for your eyes is to take short breaks. Simple one-minute eye exercises done every 20 minutes will dramatically reduce eye fatigue. Change focus by glancing at somebody’s nearby telescope. Then, lightly cup your eyes with your palms, and relax for 60 seconds. Don’t use your fingers because you might put too much pressure on your eyes. Another technique is to simply look away from the eyepiece and roll your eyes up and down, around, and side to side for 20 seconds. Then relax, eyes closed, for 30 more seconds, and you’ll be good to go.